A Community Conquers Cancer Together

Cancer does not care how tough you are or if you are sensitive to the pain of treatment. How a cancer patient copes, though, depends very much on those around her, from nurses and doctors to family and friends. They help set the tone for every stage from diagnosis onward.

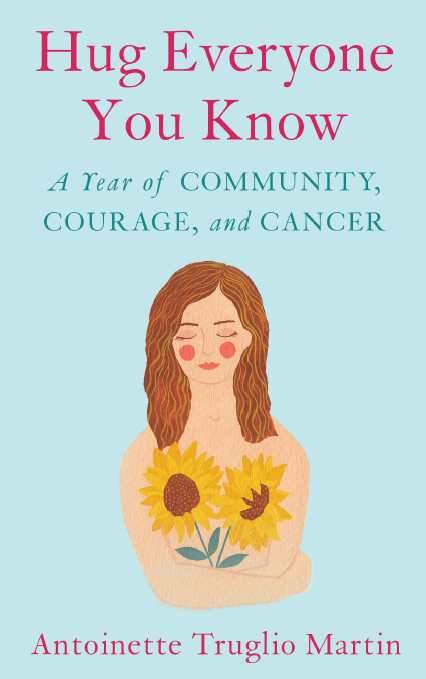

These are the basic facts that were known to Antoinette Truglio Martin when she was diagnosed with Stage 1 breast cancer. It was community that guided her through the ordeal. It took a while, but she was able to look back with gratitude and humor about her cancer treatment and write Hug Everyone You Know: A Year of Community, Courage, and Cancer, which will be published in October by She Writes Press.

As part of our focus on cancer in the month of September, I asked Martin about her support system, how she kept her sense of humor, and how she’s feeling now that she has been diagnosed a second time.

This is not only your story but that of your family and friends who supported you. How important is a community when facing a crisis like cancer?

Antoinette Truglio Martin: "I could get through what I needed to get through because I had My Everyone."

For me, my community was key in helping me navigate through that first year of cancer. I needed to feel as normal as possible during that year. I needed to be in control and be part of life’s stories. But being wimpy when it comes to any medical intervention was going to be a problem. I drew strength and encouragement from those who have known me from the beginning—my family, those who love me just because—my friends, and those who appreciate me for what I do—my colleagues and acquaintances. They were My Everyone. It was a tribe. Because My Everyone knew me, understood my shortcomings, their rally was tailored to me.

You mention in the book that, at first, anxiety prevented you from writing the “lighthearted,” humorous memoir you envisioned. How did you eventually put yourself in a place, emotionally, where you could write?

It is true. The journal entries and emails reminded me of how scared I was during that first year. There was nothing lighthearted about cancer. After a few attempts, I put everything away, not ever wanting to relive cancer again. Almost five years to the date of the first diagnosis, Stage IV metastatic breast cancer was found on my vertebrae. It’s not that unusual. Thirty percent of early-stage breast cancers develop into metastatic cancer. That is the cancer that kills.

Now I am living with this insidious disease. Although I was assured that the cancer could be managed for some time, I didn’t think I had as much time as I wanted. Suddenly my bucket list of what I really wanted to do became something I could no longer postpone. Writing the memoir, as well as a trove of other stories, was on the top of the list. I wanted to write this memoir for my daughters, my parents, and my good man. As it turned out, reading through that old journal and emails and writing the memoir honestly helped me deal with this second diagnosis. I found that despite being wimpy, I could get through what I needed to get through because I had My Everyone. It was possible to hone courage.

What advice do you have for a friend or loved one of a cancer patient? What is the right thing for them to say when they hear the news?

That is so hard. Everyone has their own perception of what they need and want to hear. It is important to know who you are trying to help. I’ve had cousins and friends who have been diagnosed with breast cancer. One wanted to know the details of what I had gone through. Others were happy enough for me to visit and bring a meal or a treat. Most of time, all that was wanted was a hug, and maybe a joint crying session. I’m very good at that. I try to make sure they know I am thinking of them, and that I am sending positive energies. Listening is best. I try to keep the “shoulds” to a minimum. I offer advice only when asked.

You spent a lot of time in clinical settings, from getting blood drawn to chemotherapy. How do you get used to strangers poking and prodding at you?

I am now a frequent flyer at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center in Commack. The doormen recognize me. I am greeted with familiar friendly faces at the reception desk. The techs remember I need to lay down for a blood draw. My doctor and nurses spend the time and want to know how all of me is doing. These angels go beyond just being a doctor, nurse, technician, receptionist, greeter, or volunteer. They are vested in making sure I am as well as possible. The least I can do is not be a big baby about it.

You are now living with Stage IV breast cancer. But you’ve decided to keep it on a “carefully watched low burner.” Is this you refusing to let it dominate your life? Also, how are you feeling today?

I don’t own the cancer. I refuse to call it mine. I never refer to it with a “my” pronoun. The cancer survivor label does not fit me. Simply, I happen to be a very nice person interested in living a life full of stories and living long enough to tell them. The cancer is a pesky sidebar.

I’m fine. I am so grateful that right now, treatment is not too debilitating or invasive. My strength and stamina may not be to my standards. There are a few things I should not do anymore, like water skiing, but I’m fine. I can do most of what I want to do, enjoy My Everyone, and be part of life’s stories.

Howard Lovy is executive editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow him on Twitter @Howard_Lovy

Howard Lovy