A Dreamy, Empowering Interview with Mira Amiras, Author of Tali and the Toucan

With a little courage and receptiveness to the wisdom hidden in dreams, yes, you too can, says Mira Amiras—and all young readers of her allegorical Tali and the Toucan will soon find themselves on their own journey to overcome their fears.

We were delighted to discover a review of Tali by Children’s Book Editor Danielle Ballantyne in a recent issue of Foreword Reviews and dreamt of learning more from Mira about the art of storytelling. The following reviewer-author conversation is everything we hoped for.

Already an accomplished anthropologist, author, and filmmaker, what inspired you to turn your creative talents toward a children’s picture book?

There’s a lot packed into your question—I’ll see if I can unpack it a bit.

As an anthropologist, I take notes, write everything down. I’ve got scraps of paper everywhere, just in case I need them. Notes. And that includes scraps of dreams. And at some point, I write about what the scraps add up to. But illustrating tales? That was knocked out of me as a child when my English teacher threw my notebook in my face from across the classroom, shouting, “drawing in a notebook is like a woman wearing falsies—all stuffing with nothing underneath.” I was in 7th grade and had no idea what he was talking about, but it scared me. I stopped illustrating my stories right then and there, keeping art and writing separate. And I didn’t come up with the obvious rebuttal until decades later: every story I had ever read for pleasure as a child was illustrated, so what was his problem?

So, I wrote without any visual embellishment decade after decade—until some of my students thought there should be a movie of what I was teaching. So much of what I taught was visual, they said, at least the way I taught it. And as it turned out, my dreams were visual too. And so—it took a very long time, but I made an animated movie of my teachings—The Day before Creation—which has won accolades all over the world. And I’ve gotten to work with talented artists and musicians and tech people. And after that, how could I ignore illustration ever again? My sadistic 7th grade English teacher was just plain wrong and it took me about fifty years to figure it out.

Many of my dreams are worth a story or two. Even my dream partner has written about my dreams. And yes, I do dream in puns. My dream-ego is a major punster—as in Tali’s dream: “First you were chicken, now you too can.” Um, should I explain about having a dream partner, or let that one go? In brief, a good friend wrote his dissertation on the dreamlife of Emanuel Swedenborg, the 18th century scientist and theologian. We started running dream workshops together in the 1980s testing out ideas in working with dreams, and keeping track of our daily dreams together for a decade or two. He’s still running dream groups. I’ve gone a different direction: writing, with illustrators, for kids.

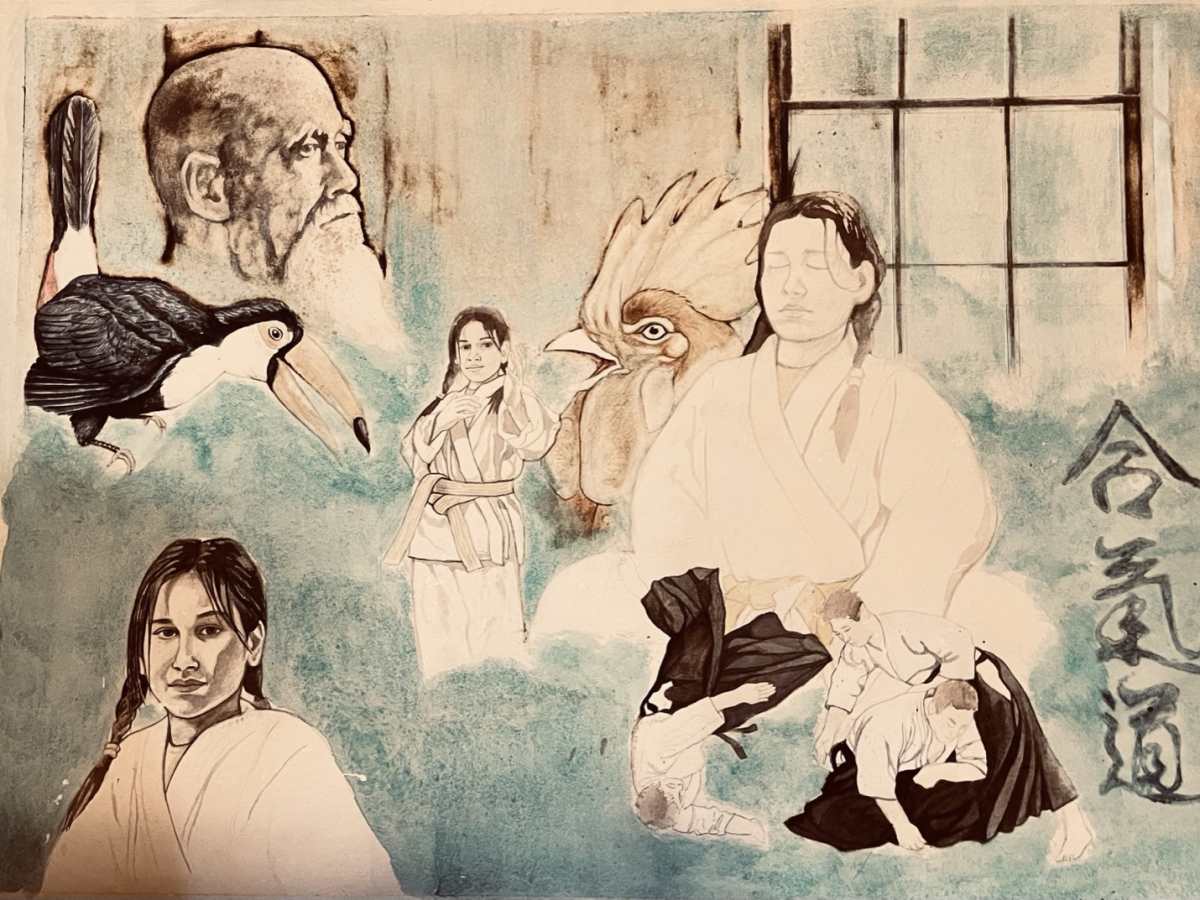

When my daughter was seven years old, she and I were both studying Aikido. And I had a dream. This dream. Tali’s dream. The scrap of paper I wrote it on is dated 1991. My daughter’s sensi was a good friend and a wonderful artist. Neil Johnson Sensei painted the elements of the story in watercolor so I could show it to a children’s book publisher I knew. It was to be called “The Chicken and the Toucan.” Perhaps it was that childhood prohibition that stopped me from sharing the story and illustration, for I never did give it to her even after she asked for it. The picture sat on a dresser for about 30 years. It’s very faded now, but here’s about what it looked like:

How was the process of working on a children’s picture book different from the books you’ve worked on in the past?

My first book was a serious tome from a serious anthropologist and aimed at serious international agrarian reform workers serving at the behest of the government in North Africa. Development and Disenchantment in Rural Tunisia: The Bourguiba Years (Westview Press, 1991) had more charts and graphs than photographs of peasant farming. It was a specialized book for a specialized audience, and I had changed everyone’s name and the names of everything except the river in order to protect human subjects.

In anthropology, “protection of human subjects” is paramount. I had also waited for the government to fall before publishing. It’s a small country and I didn’t want anyone to be hurt by anything I might say in my critique of foreign developers in the rural sector. Given that I’m still close with families in the region and no harm came to them, I believe I can be proud of that work. But after that, I wanted more life in my writing. More storytelling. More personal experiences, including my own. My writing began to change. And after I retired from the university, my audience changed as well.

By the time I thought seriously of putting the Tali story out into the world, Neil Sensei had passed on, way too young, and another illustrator came my way. First for my animated movie, The Day before Creation (2021), and then for the book that accompanies it, Malkah’s Notebook: A Journey into the Mystical Aleph-Bet (2022). Angela Engel, my publisher at the Collective Book Studio, was very supportive of these unusual projects. My illustrator was Josh Baum, an artist and a sofer—scribe of a handwritten Torah scroll. Our process included almost ten years of long conversations as we collaborated, influencing each other’s contributions throughout. After those projects, I was ready to tackle Tali’s tale at last. Josh, however, had moved on to poetry, and new illustrators emerged. This time, Chantelle and Burgen Thorne, in Kwa Zulu Natal, South Africa, award-winning children’s illustrators. They took to Tali with great tenderness and understanding. The images changed—this time, finally, I had a real live storybook for kids, more free flowing in style, word, and image.

So. Here’s what I’ve learned about myself. After decades of solitary fieldwork and writing, presenting at conferences, teaching, and workshops: I love collaboration! I love melding minds, coming up with a visual landscape for my words that I could never have come to alone. Is it too much to say that collaboration enriches and enlivens everything it touches? The result becomes more than the sum of its parts. I wish I could tell my 7th grade self that, way back then. Pictures and words: you were on the right track, kid. And collaborating with artists and musicians—that’s even better.

Where did your inspiration for Tali and her transformative journey come from?

While I don’t think I have enough imagination to just make up a story, I do have inspirations that help. Tali’s healing dream came fully-formed from a dream of my own—pun, toucan, and all. I couldn’t have made it up if I tried! And Aikido—the Japanese martial art of peace and harmony—has been an inspiration since I first learned of it. It’s a martial art that’s not about fighting, winning, or competing. Nor is it a sport. It’s a practice that changes our perspective. It shows a new angle from which to view the world (usually from the mat looking up, it’s true, but completely unharmed)

When Tali practices, she lets go of her fears, experiences trust, and establishes meaningful connections. She learns joy, compassion, and an understanding of transcendence. And it is this that helps her heal her broken world.

Glass is a thematic element throughout the book, both in the text and in the illustrations. Images of shards and shattering are used to depict Tali’s anxiety, but only by breaking the metaphorical glass that confines her is she able to be free. Did you work with the illustrators, Chantelle and Burgen Thorne, on incorporating this imagery into the book?

Dreams again. I had a recurring nightmare as a small child. It was of cosmic shattering repeating over and over. And just when you think everything’s calm, it starts up again. For years I had this dream, only to discover decades later that this shattering is described in early kabbalistic texts as a stage in the creation of the universe. This shattering features in some of my academic papers, as well as in my movie The Day before Creation. It’s also a significant feature in Malkah’s Notebook leading Malkah, trained in inquiry by her father, to crave understanding the broken world around her. I guess I just can’t seem to shake the brokenness. Tali, without Malkah’s acuity, falls into fear, anxiety, despair, and physical helplessness. She withdraws from others, her fear of the shattering paralyzes her until at last her dream life comes to the rescue. And me, I just keep writing about it.

The shattering is depicted at length in the Malkah stories. Malkah’s Notebook shows how the universe shatters and how it can be resolved. We don’t have that luxury in Tali and the Toucan—as a children’s picture book, we only have thirty-two pages to help Tali get past her terror and thrive! My illustrators for Tali, Chantelle and Burgen Thorne, were wholly unfamiliar with this principle found in Jewish mystical texts, while both Josh Baum, Malkah’s illustrator, and I had been steeped in it. So, I had the Thornes read Malkah’s Notebook to get a sense of how imbedded this shattering is within Jewish thought (not just within my own dreamlife)—, and the corollary in the Jewish practice of tikkun olam—the restoration of the world. The Thornes then came up with a unique visual interpretation that works well for Tali. Then, through Aikido, Tali begins to put the pieces back together—starting with herself.

I probably should say that Tali’s sensei is no other than Japan’s Morihei Ueshiba—O Sensei (1883-1969), the founder of Aikido itself. I’ve done this having known advanced Aikido practitioners who have at times sensed O Sensei teaching them “from the other side” and that ultimately all Aikido emanates from him even as we innovate techniques during practice. Even I have felt O Sensei teaching me on occasion, though never when I was actually practicing on the mat. Instead, he tended to come to me at night on my long commute home from the university. Pouring out his wisdom exactly under conditions in which I could never write any of it down. And so his teachings seeped into me from the ether and seeps back out in times of need.

Tali has an interest in gymnastics and martial arts. Is that something you have an interest in as well? If not, how did you decide on that characteristic for Tali?

I used to teach a class called Cultures in Conflict. I treated it as a theory course—there’s so much anthropological theory that addresses the problem of conflict. One day, a big burly rugby player who sat in the front row brought me a “present”—a pile of his old Guns and Ammo magazines. And I realized in shock that while I was steeped in theoretical constructs of the ivory tower even about conflict, my students were, well … I asked them, holding up Chris’s magazines: “how many of you have guns at home?” And every single one raised their hand, including the nun in the class. “And how many of you have ever hit or been hit by someone.” Again, all hands went up. And I felt myself an utter fraud, academic fool. For while I had been in a war and other conflict areas in the Middle East, I had never experienced personal conflict with anyone anywhere ever. I had, first of all, not even a sibling to have fought with. This was a problem. Theory alone wasn’t going to cut it.

At the end of the semester, the rugby player was graduating, and he gave me what he called a graduation present. That’s how he put it. He taught me some aspects of eastern martial arts that I could use even against a bruiser like him. And in a single afternoon, I learned to take him down with little effort if I got the angles just right. Ever the anthropologist, I began researching all types of personal combat. I took notes. I read some articles about someone named Robert Nadeau, a prominent Aikido sensei, whose dojo was in San Francisco, and I called him up and asked if I could observe.

The shock of Aikido was palpable. Tears came to my eyes that first day. It was transcendent. Transpersonal. Downright mystical. Cosmological. Nadeau created universes… He was accessing all those things that moved me in the anthropology of religion and spirituality. At the same time, it was physical, grounded, and martial. My mother had been immersed in tai chi for years, but I’d shown little interest and even less aptitude. My son studied Shotokan Karate. The San Francisco Bay Area is filled with dojos from a multitude of traditions. People practice together even in the parks. For me, Aikido resonated and I began to study. As did my daughter. She even tried to teach her dad some of the meditation techniques she was learning (the closest he ever got was Pilates, many years later). And so, as an anthropologist, this was another thing I needed to investigate. And I had to rethink how I taught Cultures in Conflict and well, everything else I did as well.

My daughter’s path led her, inevitably I suppose, to China and eventually to the practice of Chinese medicine and acupuncture. Now, as a doctor of Chinese integrative medicine, she has a clinic of her own in San Francisco. With this background, how could Tali have chosen any other path?

How Tali relates to the chicken is relatively self explanatory, but how did you settle on using a toucan as the symbol of Tali’s newfound freedom?

As I said, I dream in puns. It’s embarrassing really, but instructive. I almost never pun in waking life, and certainly don’t do it on purpose. But dreams are like telegrams—short and to the point, and apparently punning is a fairly common shortcut dreams employ to get there quickly. And like political slogans or TV jingles, puns are easy to remember. I woke up, laughed, and remembered.

In writing the story, I did feel I ought to research toucans. As well as that beach where Tali’s palapa is located. Turns out, she’s dreaming of Acumal (before the tourist hotels invaded). Turns out, toucans are not the best at flying and they certainly don’t do somersaults. Nor do they live anywhere in San Francisco, not in nature anyway. But they are seen painted on the streets of the Mission District, and it is from the Mission, surely, where the toucan followed Tali home one night inside her dreams. But toucans do do something no other creature on earth can: they too can. And that’s the lesson the dreamworld handed over to Tali. It was that simple. No other bird would do.

Finally, can you tell us what’s next for you? Any upcoming projects we can be on the lookout for?

Well, next I’m teaching a course at New Lehrhaus in Berkeley, CA. September, 2024. The class is called How the Middle East Works: Four Models. It’s a class intended for grownups. I’m really looking forward to it. Though I have a feeling that Tali will want to have a crack at it too at some point.

Looks like there may well be a lot more Tali stories coming. She’s got a lot to teach.

The next Tali tale—Tali and the Timeless Time (forthcoming 2025)—is inspired by memories of my nona (Ladino for grandmother) when her mind was starting to slip. In this tale, nona is trying to transmit Sephardi culture to Tali, but she gets the past and the present all mixed up and doesn’t recognize even things she’s just taught Tali. She is slipping into “the timeless time,” with Tali by her side trying to ground her.

The Tali stories to come, like Tali and the Toucan, explore real-life fears, anxieties, and problems that are worth thinking about—for children and grownups, and both together—shifting our perspective just enough to experience alternate ways of being. Leading eventually—if I’m brave enough, and live long enough—to tell a tale in which Tali can reconfigure the entire Middle East. Yes, I’m serious. If diplomats and warfare can’t do it, what if the dreams of a child can show the way? Is this a children’s book, you ask? Dr. Seuss tackled nuclear holocaust, as I recall. Surely Tali can take on the Middle East!

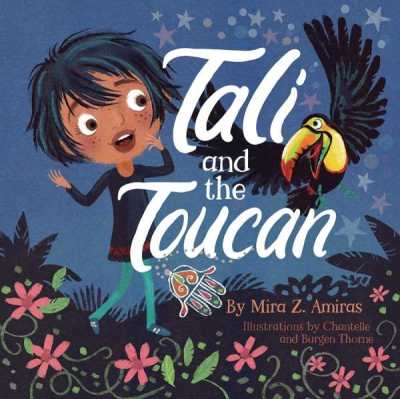

Tali and the Toucan

Chantelle Thorne (Illustrator) Burgen Thorne (Illustrator)

The Collective Book Studio (Aug 27, 2024)

Emotive illustrations track the transformation of a girl as she moves through her fear and finds resolve. Tali longs to tumble and soar like the other children at gymnastics or the dojo, but fear always stops her from trying. Through a series of dreams, she discovers her courage—and herself. The illustrations artfully capture the shifting, high-stakes sensation of dreams and the all-consuming nature of anxiety in this picture book that validates children’s fears before gently encouraging them to face them.

Reviewed by Danielle Ballantyne July / August 2024

Danielle Ballantyne