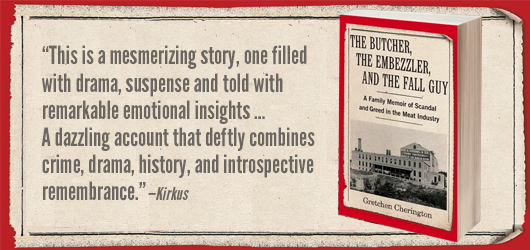

A masterful true-crime story of ambition, intrigue, and the early Hormel company

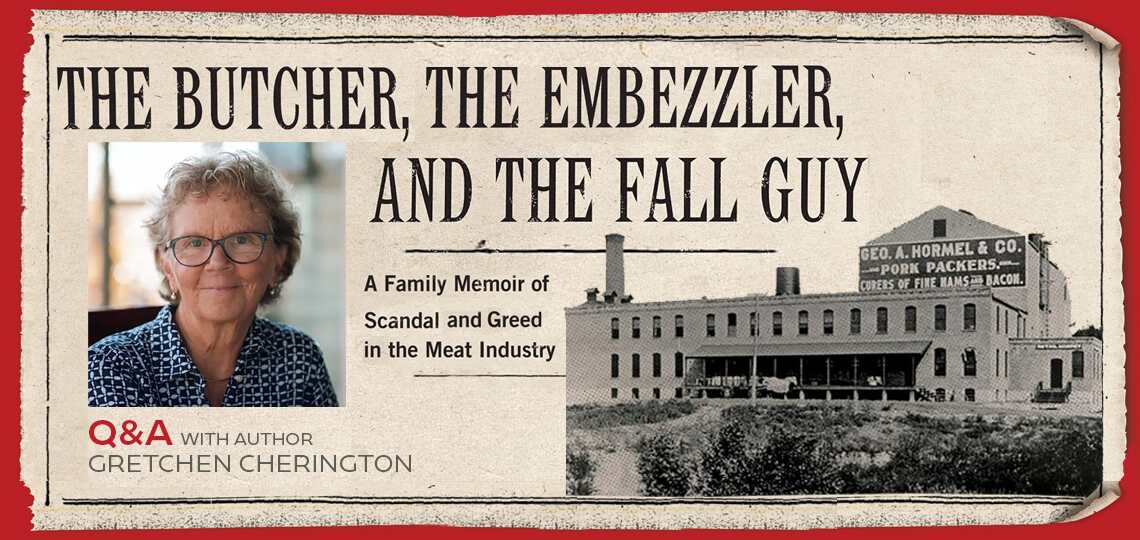

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Gretchen Cherington, Author of The Butcher, the Embezzler, and the Fall Guy

Answering the “where we came from” question is universally appealing, which is why countless people lean on genealogy websites like Ancestry and FamilySearch to learn more about themselves through the lives of their ancestors.

And yet, some of us look back and see a looming, larger-than-life presence that plays an outsize role in family history. Which is the case for today’s guest, Gretchen Cherington, whose grandfather was largely responsible for helping what is now Hormel Foods become a favorite part of America’s kitchen table for over 100 years. But a scandal back in the early days of Hormel and her grandfather’s unexplained departure from the company complicated the story—and set Gretchen on a research mission to find out the truth, all detailed in her fascinating new book, The Butcher, the Embezzler, and the Fall Guy.

With our own questions top of mind, we put Executive Editor Matt Sutherland in touch with Gretchen for the following conversation.

Hormel is a multibillion dollar food processing company and your grandfather’s sales leadership is widely credited with playing a leading role in its success in the early 1900s. But after a massive embezzlement scandal in 1921—$18.7 million in 2024 dollars—by a company employee named Ransome Thomson, George Hormel forced your grandfather, Alpha LaRue (A.L.) Eberhart, to resign for dubious reasons. These spare facts have been part of your family history your whole life. Can you talk about that need or desire to dig deeper into the story in order to write this compelling book? Would it be fair to describe it as an effort to clear your family name?

My curiosity was piqued as a kid listening to my father’s riveting stories about these three men. Present in his telling were themes of great wealth and greed, crime, and family drama–all terrific makings for stories, and for years I took them as fact. As I matured and had experiences that sometimes contradicted his versions of the same, I began to wonder what was really true. Was George Hormel the “bastard” my father described; was A.L. the “six feet of manhood and not a mark of fear” Dad had penned in one of his poems.

My drive to understand what really happened was cemented through the first half of my career in consulting to entrepreneurs and CEOs. As I observed my clients’ ambitions and motivations, their strengths and flaws, I wanted to train the same objective eye on the three executives who’d occupied such psychic space in my family.

No doubt, in some moments, I felt like clearing our family name. But that was never the book I wanted to write. I’m often searching for a central, sometimes emotional, truth in a story, informed by my own lived experience and regardless of where that search takes me. Our culture mythologizes men in power and I wanted to resist that easy pull as I got to know my grandfather through his archives. It’s these mens’ flaws that drive my conclusions and make up what to me, now, seems like an avoidable tragedy.

Your many years of professional consulting work allowed you contact with leaders of some of the top corporations in the world. Did this proximity to power and alpha men provide you with insight into George Hormel, Cy Thomson, your grandfather, and the turn-of-the-century meatpacking industry as a whole?

Absolutely. My consulting work gave me a unique window into these three characters while they were building Hormel’s early success. I was working with CEOs who had ambitious vision and good intentions, yet none was devoid of blinders. I suspected I’d find the same true with the Hormel men if I allowed myself to be open to that. Because I never knew my grandfather, Hormel, or Thomson personally, I had to do a lot of research and use some speculation based on my own experience, in order to build their Minnesota meatpacking world and to examine how they each wielded power.

Upton Sinclair’s widely acclaimed 1905 fictional exposé of the meatpacking industry, The Jungle, repulsed the nation and spurred President Theodore Roosevelt to introduce the first regulatory food laws. Can you give us a peek into turn-or-the-century slaughter house practices? Was Hormel just as bad as Swift, Armour, and the others? How did George Hormel and the company respond to the new laws?

Early slaughterhouses were visceral; usually cramped spaces filled with sights, sounds, and smells of human sweat and animal blood. Meat plants were frigid in winter and scalding in summer. Filled with new immigrants doing tough jobs in tough conditions, their bosses were sometimes ruthless. Before mechanization, the workers cleaved animals by hand, hung them to bleed out, then sawed and cut them up for packaging.

In that context, by all accounts, George Hormel’s early insistence on plant cleanliness (a principle learned from his meatpacking uncle in Chicago who taught him that only “clean meat sells,”) was noted when the first federal inspectors arrived in Austin, Minnesota. They declared the Hormel plant among the best they’d seen which led to an increase in demand for Hormel meats. That obsession for cleanliness got greased into the company’s DNA.

George Hormel was a stickler for details and greeted the new federal laws with equanimity, having called for meat industry leaders to regulate themselves or the federal government would do it for them. He was frequently prescient about where the world was headed, being among the first in his industry to hire Black Americans and women, to introduce safety measures, and to pay his workers better than industry standard. But to this day, meatpacking is a tough business and it’s still filled with new immigrants willing to work in rough conditions. In some places, they still fill jobs on the “chain” with titles like “knocker” and “breaker.” My research was focused on the industry’s early days but the internet is replete with accountings of current-day packing plants, both complimentary and scathing,

By comparison with Swift and Armour in 1905, Hormel’s company was a much smaller operation and just getting started. There was little bureaucracy; the executives probably knew most of the workers. And none had yet reached the stature of Gustavus Swift or Philip Armour who’d already been around for decades.

What kind of guy was George Hormel, founder?

He was a complex human being. One of twelve siblings, he grew up poor and left school at ten to skin hogs in his father’s Toledo tannery. He left home for good at thirteen to find his way in the world and by the time he’d settled in Austin, four hundred miles from Chicago (then the “meat capital” of the world), he’d conjured a striking vision to build his tiny meatpacking factory into a worthy competitor for the Chicago giants. In part, his motivation was to leave behind the butchering day-labor of his ancestors to become a company owner.

But he could be a tough boss, described by some I met as a dictator. And he trusted his personable, smart, and wily comptroller Ransome Thomson for far too long. Hormel’s denial matched that of everyone in the region who considered Thomson a benefactor and friend. This story is an object lesson in collective denial at the hands of a con man, something we still see today. When the company nearly failed, Hormel sacrificed his executives, including my grandfather, who’d helped turn his enterprise into a national brand. He’s a fascinating example of an early US entrepreneur, one I’ve come to see with nuance.

And your grandfather, A. L. Eberhart? Why did George bring him on in the first place? What was A.L. like?

I speculate that Hormel recruited A.L. for his greater knowledge and experience in the meat industry, especially in merchandising and sales leadership, for which he was known as he’d climbed the ranks of Swift & Company in Chicago and St. Paul. Also, to Hormel’s credit, he may have predicted that A.L.’s temperament and disposition would complement his more autocratic style. A.L.’s talent was in sales but he was known for motivating his men and for keeping his word. With a different upbringing–and long accustomed to wearing hand tailored suits–he could help George Hormel realize his vision.

In 1908, Lillian Hormel and Lena Eberhart, your grandmother, were appointed to the board of George A. Hormel & Company, a position they both held for the next six years. Can you speak to what this represented? For women of the era? For women in the meat industry? For Lillian and Lena’s relationship with their powerful husbands?

At first blush, it’s astounding, but both Lena Eberhart and Lillian Hormel were full partners to their husbands’ careers, with inside knowledge. Each was smart, independent-thinking, and highly regarded in Austin. These qualities alone made them good prospects for a board, even as they also played more traditional roles as product taste-testers and recipe-creators. But family companies tend to hold their business close to the vest, so maybe this was a safe move, too. I wish I knew why their tenure ended, but I’ve seen no record for that.

Cy’s path to embezzling more than a million dollars started as early as 1911, when he pocketed $800 of money that was mailed to the company to purchase stock certificates. As he later wrote from his prison cell, the theft was “sheer impulse,” and he himself never quite understood why he took his “first step into the quicksand.” Even so, for ten long years he shrewdly used the ill-gotten money to invest in real estate and agricultural businesses, as well as some impressive philanthropic enterprises. After all your research, how did you come to feel about him? Did you grow more, or less, sympathetic towards this Minnesotan Jay Gatsby, as you once referred to him in the book? Why did he write an autobiography?

Cy Thomson was also complicated, with drive like that of Hormel and Eberhart, but without their scruples. Like Hormel, he was brought up poor, in a pioneer farm family in northern Iowa. More than anything he too wanted to succeed above his station. It’s hard not to marvel at his vision and ingenuity in creating OakDale Amusement Park, an early precursor to Disneyland. If he’d created it with legal money, it might still be going strong today. As his greed for wealth and notoriety increased through the years, he obtained–at least temporarily–what his bosses had earned legitimately.

From behind bars, I suspect he wanted to keep his name alive. And he wanted sole credit for the embezzlement while thumbing his nose at the executives who took so long to catch him. Imagine what Thomson could do on X, today!

We now know that embezzlers require three conditions to commit their crimes: opportunity (in Thomson’s case, he had nearly full control over the Hormel books), pressure (his was the internal pressure to outdo his beginnings), and rationalization (I cover several possibilities in the book). Some readers have been so fascinated by both Hormel and Thomson in this book that they’ve gone on to read their autobiographies.

Through my research and writing, I developed a far greater understanding of and appreciation for the terrible impact Thomson had on southern Minnesota–not just on my grandfather’s wealth and the Hormel company, but on his own friends and colleagues and his own employees at his OakDale Farms and Amusement Park. Really, just about everyone who lived and worked in southern Minnesota. That impact was both economic and emotional. The specter of Thomson still lives there today, a century later.

Through profit sharing, generous bonuses, and a good salary, your grandfather became one of the wealthiest businessmen in southern Minnesota. He and his family lived in beautiful homes, traveled extensively, and further invested in real estate around Austin, including a 160 acre farm where he raised award-winning Holstein cattle. Was his boss, George Hormel, supportive of A.L.’s outside investments? Were the seeds to their eventual breakup laid from much earlier in their relationship?

This is one place where I part with my family’s story of A.L.. I doubt George Hormel was pleased with A.L.‘s outside enterprises and yet I doubt he laid down a clear rule about them either. Plus, from what I’ve been told, everyone in southern Minnesota at that time had livestock (“it’s what we did,” I heard). Possibly A.L.‘s outside interests weren’t so different from the cultural norm. You’re right, though, that one of A.L.’s flaws was not to have predicted that his outside attentions could sour his relationship with his boss. But then our blinders often only make such things clearer in hindsight.

A few months after Cy was sentenced to fifteen years in jail, George and his son Jay cut A. L. loose—as your grandmother Lena was in the late stages of cancer and bedridden. Your father, Richard Eberhart, wasn’t quite twenty at the time and served a caretaker role for both his mother and younger sister, Elizabeth, while the oldest son, Dryden, was away at university. This must have been an extremely difficult time. But A.L. soon moved on to new jobs and remarried a couple years later. And your uncle and aunt both seemed to land on their feet. How did those trying years mark the family?

By way of A.L.‘s letters and business documents, it’s been eye-opening and a privilege to witness his navigation through several years of sheer hell. This project gave me both admiration and love for the grandparents I never knew.

The legacy of Austin weighed significantly, if differently, through the family branches headed by my father, my uncle, and my aunt. There was shame, I believe, though the word wasn’t voiced in their generation. There was anger at George Hormel and disbelief that A.L. had any direct connection to the embezzlement. Even in June, at my book launch in Austin, I heard from those whose parents or grandparents knew mine that their families never believed A.L. was complicit in the crime.

A.L. and his three children did land on their feet. My uncle Dryden became a prosperous financial executive at Eaton Vance and contributed many years to helping A.L. untangle his holdings both before and after A.L.‘s death. My aunt Elizabeth was a successful social worker into her 70s. Each of them lived solidly in the real world, each likely evolving their perspectives as they matured. I think my father’s felt trauma was greater or at least it persisted as fixed through his own life. His maturation into adulthood took longer than for his siblings, though each reached success in their fields (I cover my relationship with my father in my first memoir, Poetic License).

Your father became an esteemed poet and literary figure with a list of friends and confidants that would turn the heads of just about any student of twentieth century literature: Robert Frost, Allen Ginsburg, and so on. But as you describe in the book, your relationship with him was complicated not least because he sexually abused you. Can you talk about the person you are in light of that relationship?

His abuse was formative to who I am, first for it leading me to secret the truth away, before eventually dealing with it. That pivot required a deep dive into everything I’d held as true. I needed new skills and behaviors to shed my own shame. The trade-offs weren’t always easy. Only in retrospect can I see how that experience also propelled me to work with other powerful men, albeit in the business world, as I came to terms with my father. Clients provided examples of how male power held sway in social institutions, be they corporate or familial. I’m no longer intimidated by powerful men or the mythologies they/we create around them. I understand the systems that continue to support them and know how far we still have to go.

Are you currently working on another writing project? How is retirement treating you?

I’m a fan of “retirement,” though when I’m on a book deadline my days hardly feel like the ones I probably imagined a decade ago!

And yes, a third book is in the works; also based on a true crime, but told through fiction. I’m still mapping it out; playing with my options; and granting myself time. Thematically, it will continue my fascination with complex family stories. But this time, not mine!

For bonus content and more information go to gretchencherington.com

Matt Sutherland