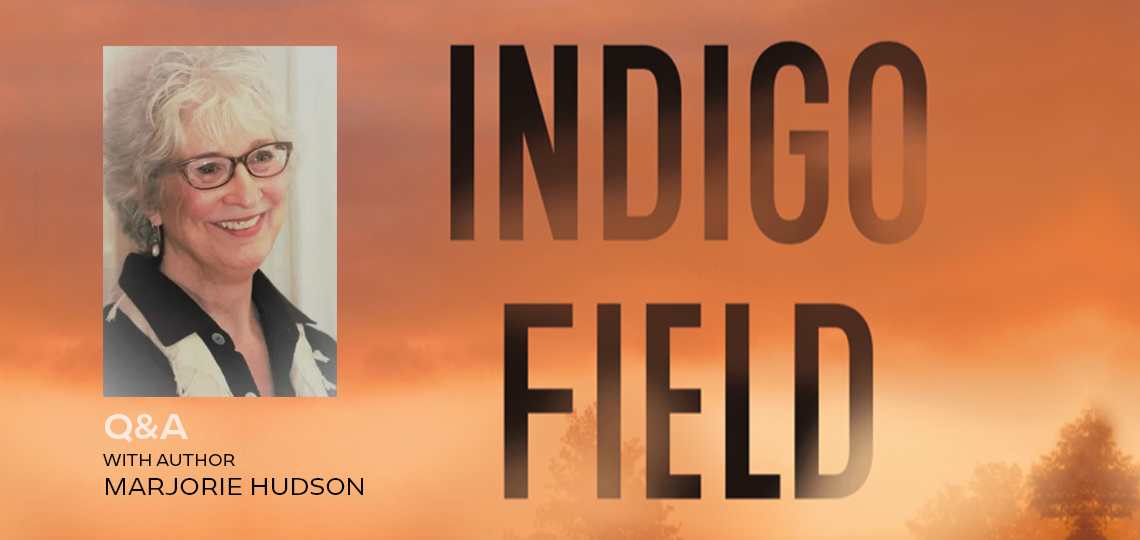

A Mystical Field in the South, A Reckoning with Difficult History

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Marjorie Hudson, Author of Indigo Field

Everyone who has ever been given the privilege of recording history has suffered from the same set of conflicting pressures—1) tell the truth, 2) earn the esteem of your reading audience. Very often, the task is next to impossible. And that’s why unflattering history has always bedeviled the historian.

But not telling the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth can cause grave harm to those who end up on the cutting room floor. Alas, in the five-hundred-year story of the Americas, all-too-many historians, mapmakers, and opportunistic settlers used their position to record a selective version of the truth at the expense of this land’s Indigenous and Black peoples. That’s where a novel like Indigo Field can provide deeper understanding.

In her recently released novel Indigo Field, today’s guest Marjorie Hudson tells an enthralling story about contemporary Southerners, one of whom has secret knowledge of the early Carolinas, a place where European colonizers methodically erased the landscape of as many as twenty Indigenous tribes over the course of centuries. Marjorie’s Miss Reba, the heart and soul of this multi-character, multi-generational novel, reveals her family history from the years following the Civil War and into the mid twentieth century when the remnants of those tribes and handfuls of Black descendants of the enslaved fought to survive with all manner of odds against them.

Matt Sutherland fell hard for the story and jumped at the chance to engage with Marjorie for the following discussion. Should you be attending ALA’s Annual Conference in San Diego this June, don’t miss Marjorie’s book-signing giveaway at the Independent Publishers Group (IPG) booth.

Bravo. Utmost admiration. Superb voices and wordplay, incredible story, multiple stories. But, considering everything, it’s apparent to me that Indigo Field is a love letter to birds and to trees. Do I have it wrong?

Matt! Thank you! And you’re absolutely right. Indigo Field really is a love letter to the diverse community where I live, including the birds and trees—who by the way are still the dominant citizens where I live just like in Indigo Field. I fell in love with my part of the rural South, fields and pine forests, small towns and rivers, Black and white and Indigenous people living side by side historically as well as now. Living out in the country was a hard left turn from living and working for a nature magazine in Washington, DC. I now have time to be in nature every day!

The Carolinas. Can you talk about the “various spiritual forces” at play in the region and why you were drawn to telling this story in this place?

The ground is blood-soaked here. Entire cultures have disappeared. The South is where Europeans first encountered and fought Native people—battles that most people don’t know much about. This was also the battleground for freedom from the great sin of slavery, for voting rights for Black people, and freedom from the terror of Jim Crow. Where are the bodies buried? In unmarked graves. The fields are haunted by stone tools and arrowheads, and the forests are haunted by lynching trees and the memory of flaming crosses. As a newcomer I began to notice there was history we didn’t talk about. I can feel the spirits rising even now, when I see an empty field next to a river.

Can you give us a brief history of the Tuscarora, Lumbee, Occaneechi Band of the Saponi, Hatteras, and other Indigenous people of the Carolinas, as well as the Tuscarora War? And also a sense of your research for the novel?

It would not be brief! I’ve written and researched about this for my first book, Searching for Virginia Dare, about the famous Lost Colony. So let me start with that.

One of the early moments of contact between English and Indigenous people in the South was on Hatteras and Roanoke islands on the Outer Banks—a disastrous attempt by Queen Elizabeth at colonization in 1587. The descendants of that colony “disappeared” but there’s good evidence they survived by living with and making families with the Hatteras/Croatoan Indians.

Over a hundred years later John Lawson (the explorer mentioned in the novel) documented Indians on Hatteras Island with gray eyes who claimed to be descended from the English. Lawson documented the Tuscarora and twenty other smaller nations more inland in the Carolinas. By the time Lawson published his book about them, the Tuscarora were ready for war. New Palatine settlers at New Bern were selling their children into slavery, shooting their game, and giving them deadly diseases that included the common cold. The Tuscarora attacked the settlement and slaughtered them all. When my character Tuscarora Lucy tells her family history, it’s based on this true story.

When the colonial English mustered to fight back, the war spread to South Carolina and ended up fracturing the entire tribal system Lawson had documented. The Tuscarora either went north to the Iroquois nation, made deals to stay on reservations, or hid away and formed raiding parties. Most tribal people joined forces with survivors in small bands. On the border near South Carolina, Lumbee people took in many emigres, swelling their ranks, hidden away along the swamps of the Lumber River. As far away as Virginia, the Occaneechi migrated southward to North Carolina and joined forces with the Saponi. This was a pattern all over the South—and it continued as European settlements moved west.

During a certain part of Southern history, Indigenous people seemed to have mostly disappeared, but there were reports of raiding bands of Tuscarora into the 1750s. I was fascinated with this period, where English, Scots, and German settlers came down from the Great Valley of Virginia to virtually empty land and claimed it, finding arrowheads, abandoned crops, and stone tools. Our neighbors still find stone tools all over their farms. What really happened? Indigenous people survived by becoming secretive and joining forces. When I began to meet some of the survivors of various nations among my neighbors, the story became even more fascinating to me. That was a big part of the inspiration for “Indigo Field” in the novel—a fictional field whose name on present-day maps in the story hides the “true name” of the place: Indian Field.

Your novel doesn’t shy away from North America’s bitterest historical truths about the treatment of Native Americans, Black Americans, women, and people of special needs, among others—at a time when talking about such things is shunned by certain quarters. I was pondering a question along the lines of Do you have a message for those people who would like to bury that unflattering history of how European men settled this land and proceeded to rule?

And then I read this passage from the inner voice of Reba and quickly understood how you’d likely answer: “I keep Sheba company in her cornpatch grave, listen for her voice in the hickory grove. I close my eyes and wait for a vision of how whitemen might be brought low, how the Lord might smite them for their wickedness. Put the Black people on top of His holy mountain. Indians too.” Would you talk about Reba’s understandable bitterness (hatred) toward white men, and what, if any, message you have for those who would like to sanitize history?

I think we do so at our peril. The “Big H” history that leaves out stories of the traumatic past is just like personal history in a way—it seethes beneath the surface and defines us if we try to repress it. We become stuck in a loop of underlying resentment, unspoken rage, and hurt, just like my characters Miss Reba and Rand, the retired colonel who lives across the highway. We also miss a lot of great stories, fascinating people who have a lot to teach us and whose stories can bring us together if they are given light of day. Another inspiration for writing this novel: One day I discovered who my daughter’s middle school was named for—a Black man. Nobody else seemed to know; that is, white people in my community didn’t know. Black people did. Because they’d handed down the story since the days before integration, when it had been a “colored school.” The original school had been named for the first Black man who published a book in the South. He sold his poems to buy his freedom. The more you peel back the onion, the more inspiring the story is. It’s about struggle, artistic expression, finding allies, fighting for freedom. Now we’ve claimed his story and it has become part of school pride and curriculum, celebrated every year.

So what I have to say to folks who are uncomfortable with raising difficult truths from our American history is this: don’t turn away. Embrace the difficult. It can give you extraordinary and surprising ways to come together in community. In my novel, the deep bitterness of Miss Reba’s vision of destruction has a chance to be burned away and transformed because as her stories rise, spirits rise, and have their say.

At one point in the book, as they investigate ancient gravesites in the area, archaeologists Chuck and Jeff talk about Chuck’s theory of historical erasure, and specifically, in the case of Indigo Field, how it was originally named Indian Field. How common was this practice in early America?

I’m fascinated with old maps of my area. They are documents made by English or European people, of course, and they show what mapmakers thought was important—which, of course changed over time. A native settlement might be indicated next to a river ford, or “crossing.” On the next map, the settlement might be missing, and a mill is there instead. Later, a bridge replaces the ford—people with grain need to know it’s easy to get across the river. The names of these places might be English, or German, or Scottish. But often river names stay the same, Indigenous names shimmering with the memory of the peoples who ruled the land originally.

Fun fact—we were just looking at an old deed for a family farm. It does not contain any indication of Indigenous settlements, but the creek through the farm is called Little Coharie Creek. The Coharie still live in the area and hold an annual Pow Wow. I’ve found this phenomenon over and over as I travel the South. Tribal people who once hid their identity are going public, setting up websites, holding Pow Wows, rediscovering their languages, their family connections. During Jim Crow, such people were often persecuted, hanging on by a thread, hiding away as best they could to be safe. They had even fewer legal rights than Black people.

In the novel, when Chuck shows Jeff the map, he doesn’t know about Tuscarora Lucy’s “devil’s bargain” with Johnston Blake—she gives him deed ownership of her land in exchange for an agreement of protection by “disappearing” the existence of her hideaway there—that is, leaving “Indian Field” off the map to keep her safe. She knew ownership by a powerful white man would be respected. There was no guarantee that her right to the land would be. This bargain is from my imagination. But I do know that land rights of Indigenous people were always in jeopardy, and sometimes they found white allies.

Miss Reba, still distraught about the murder of her niece Danielle months ago, is increasingly experiencing visits from the barely visible spirit of her beloved niece, who has come back as a little girl. Danielle starts speaking to her plain as day, which isn’t supposed to happen according to Miss Reba’s knowledge of spirits. “‘The girl is here,’ she thinks to herself, and ‘who knows what the rules of spirits are. … This is the price, it seems, for keeping this child spirit close and her own heart alive.’” From here, you use a wonderful flashback device to retell stories from Reba’s childhood, by way of Reba talking to her long-passed Danielle who’s begging Reba for stories about Reba’s sister, relatives, and the burials in Indigo (formerly Indian) Field. How did you arrive at this storytelling technique?

In first draft, Miss Reba’s family stories were told in a big Faulknerian third person voice, giving a sense of legend and mystery. I was very proud of that voice—it was strong, poetic, compelling. But there was something wrong. I realized I was mediating her story as if it belonged to a white literary tradition. Miss Reba wouldn’t have liked white people telling her story in their voice—for one thing, it was a secret. She wanted to tell the stories to her beloved dead Danielle, no outsiders. So she took over, telling her own story out loud to Danielle’s spirit and the other spirits of her family, using her own voice, sitting in her porch chair.

Of course, Miss Reba’s secrecy is foiled by that nosy white boy TJ spying on her from the porch roof. TJ, an ignorant teenage boy, an innocent with a true heart, gets access to her secrets in a way that is a kind of transgression, but leads him to a better understanding of Reba, of Tuscarora people, of secrets, and eventually his own identity.

That “stories out loud” technique, I realized later, reflected something I’d learned in historical research. The “true” stories of Indigenous and Black people available in historical collections are most vivid in oral histories, unmediated by scholars’ interpretations.

Tuscarora Lucy, the Black-Indian who lived for many decades on a hidden island near Indigo Field after her people were killed, befriends adolescent Reba and her older sister Sheba and teaches them the old ways. After a terrible incident in early adulthood, Reba escapes to Lucy’s cabin and lives with her for six years learning the skills of midwifing, using powerful herbs, the legends and lessons of her Black-Indian ancestors, and how to make fiery white hooch from the still down on Spill Creek, formerly Still Creek. Is there some historical basis for Lucy’s character? How were Black-Indian relations through the eighteenth and nineteenth century in the Carolinas?

“Black Indians” are a common phenomenon in the South. Many people who identify as Black don’t know they have Indigenous heritage. Many indigenous people have Black heritage. The US census did not record Indigenous identities and did not record last names of Black people who were enslaved. When a Black grandmother I knew told me, “Our people were never slaves. They were Indians,” I was surprised. But I shouldn’t have been. I knew the migrations of Black and Native people in the years after the Civil War resulted in mixed settlements. It’s also true that Indigenous identity is intentionally repressed sometimes. A friend confided that her seemingly white adopted daughter was Lumbee. (Lumbee people have absorbed so many cultures of people, they come in many colors, including white.) The adoption agency told her: “Never tell her about her heritage.” The Lumbee people were so victimized by whites in those days, by the court system, by the Klan, by poverty, I think the agency’s idea was that it was in the child’s best interests to pass as white.

Tuscarora Lucy came to me entirely from imagination. But she answers one of my enduring questions: how could an Indigenous person survive in the 1800s if she was the only one left of her people?

You begin the book with Col. Randolph Jefferson Lee, lousy husband and father, anti-social to friends and strangers alike, struggling in his early retirement to find something, anything to do with himself, as his wife, Anne, keeps up a breathless schedule of volunteer work, socializing, tennis, and more. And then she suddenly dies playing doubles one morning. Rand unravels, leans into tumblers of bourbon, and lashes out at anyone who comes near, including his daughter and son. And then, battling for their lives in a cataclysmic hurricane, Reba and Rand connect and their subsequent friendship brings Rand back from the brink. Rand’s introspection over his marriage, military career, and reprehensible behavior is some of the most compelling material in the book. How was it to get in the head of such a conflicted male mind?

I love Rand, flawed as he is. He’s a person who doesn’t know himself deeply, covers his pain with pride. He’s ignoring his past sins, pretending they don’t matter, but underneath there is a load of guilt. He’s a retired man who’s a fish out of water, who is running away from his conflicted mind, his misery, by running, literally. I go to book clubs in retirement villages and the women often say to me, “I know somebody like that.” The ladies around the circle nod knowingly. Or they laugh. They’re thinking of their husbands.

With Rand, I noticed he was prideful from the first time he stumbled while running, and women were watching. I noticed he was insecure when he didn’t like the “better than you” retirees living around him. I noticed he was afraid when, in the novel’s first pages, he wondered if his wife was thinking about Malaysia “and all that happened there”—but didn’t ask her.

I think it’s hard to be a prideful captain of industry or a colonel and end up retired with nothing to do. I have a lot of sympathy for that. A powerful man in our culture can find comfort in challenges like golf, or world travel, or drinking, but I believe Rand needed (and lots of retirees need) a more meaningful end-of-life challenge—in his case, finally finding a way to make a difference for his impoverished neighbor Miss Reba.

Getting inside Rand’s head wasn’t hard once I figured out his backstory—a boy so devastated by poverty and loss that he had to run away. That vulnerability made him blind, because his coping mechanism is pride. He doesn’t see what’s going on right in front of his face. He doesn’t see himself. He’s so busy hiding his “true self,” his past. My job was to bring him low, force him to see who he really is, and regain his pride by helping someone. Because I needed to poke his pride bubble and his self-centeredness, I sometimes made fun of him. He talks to his tropical birds, throws bird parties. He gets dumb ideas like setting them free. He disrespects his son, makes claims to superior knowledge about Tuscarora people, and is completely wrong about a lot of things. In the climactic scene with Miss Reba, his inner monologue is all foolish: he convinces himself that Reba is a maid, or a nurse. But Miss Reba knows exactly who he is.

Three-plus pages of acknowledgements show that you received an extraordinary amount of encouragement, support, guidance, and more from many dozens of individuals and organizations. All of which might give the average reader some indication of what it takes to pull off a novel of this scope. Did you know what you were getting into from the outset? How important were your early readers?

I’m so grateful to my community! This novel, with all its layers of history, character, backstory, and present drama, along with the trajectory of a living place with a plot arc of its own, took a lot of reworking and a village of readers. I started with a big idea: A novel about newcomers and old-timers in a rural place, about how they rarely cross boundaries to know each other. I wanted every character to have a transformation, a kind of “hero’s journey” in the Joseph Campbell sense. I wanted the story line to end in a kind of shimmering place of understanding. Also, I wanted to say something about the repression of history and identity of Black and Indigenous people, how it must rise, especially in the South. I had a lot of help, and did a lot of research. A lot of my calling to write about these things came from being in community as an activist who spent time with all different kinds of people. At the end of day, I felt like I was standing on a little hill, looking at the big picture that others couldn’t see. People talk about writing from identity. My calling was to write from community.

And yes, I had no idea what I was getting into. It took thirty years. But I’m glad I took that time because I began to know more, feel more, and layer more meaning into the story. I wrote on my own for about six years. I had four hundred pages in 1999. Six hundred about ten years later. That’s when I shared the whole thing with my writers’ group. Poor writers’ group! Then major revisions, over and over. More readers. Then cuts and more cuts. It took that long, and it took that distance, to really see what I wanted to do in a big book like this and to take the time to refine each sentence, each line of dialogue, each plot line, each detail of the seasons of nature.

Who is the ideal reader for this superb novel?

Someone who cares about social justice, inner transformation, history, and the spiritual qualities of trees. You don’t have to be from the South to read Indigo Field, but that could be an added interest for some.

Are you currently working on another writing project?

Yes! But I’m not telling.

What about all those birds? Wild birds, migrations, tropical birds in cages …

I am a freak for birdwatching. I’m not saying I’m much good at it—I learn a lot from my husband, who has a great eye and ear. Our farm has a great ecosystem for birds of all kinds. We’ve seen eagles (twice), osprey (occasionally), whippoorwills (fewer now, because of coyotes), the mating dance of the woodcock (it flies straight up in the air just before dawn and makes a buzz-twitter sound), and every kind of songbird you can imagine. Because we spend a lot of time outdoors in the garden or doing chores, we call out bird sightings (and hearings) to each other. Such a pleasure to discover something new, or see the first hummingbird of the seasonal migration, or a new nest or mating pair.

I’m also a freak for parrot colonies found outside their natural range. They really are all over North America and Europe. I’ve tracked them down in Rome and San Francisco and there are famous colonies in London, Connecticut, and I think even in Chicago. Where in the world do they come from and why do they stay? I gave my obsession to Rand as his passion and hobby. These colonies are also a metaphor for the colonizing of the New World—a sort of reverse colonization. I’ve read so much about the Carolina Parakeet (now extinct) in historical material. I enjoyed bringing them in.

The thing I didn’t know much about was caged birds. I had to do a lot of research about those. A writer friend took me on a parrot tour of Durham, NC (thanks, Frances!). She took me to a bird cocktail party—parrots out of their cages, flying around, drinks for them, drinks for us, little plates of snacks for all, lots of loud chattering, quite hilarious. Then she took me to a carwash where they had a huge green parrot in a huge cage who would sing “Let me call you sweetheart” to any woman who came up to him. Lots of funny head rolls and bird flirting. I perform his act at book clubs, it’s a big hit, though I’m sure the bird is a better singer than me. Then I went to a bird rescue and stood before an enormous magenta cockatoo who was missing his people—I think he’d been left there for over thirty days. He was plucking his feathers out of his chest and just a membrane was left over his heart. I stood there a while, trying to connect, to get him to calm down. I could see that he was grieving deeply. That’s when I learned that birds grieve when their people (or bird companions) abandon them. And dealing with grief is something they have in common with all of us, and with the characters in Indigo Field.

Matt Sutherland