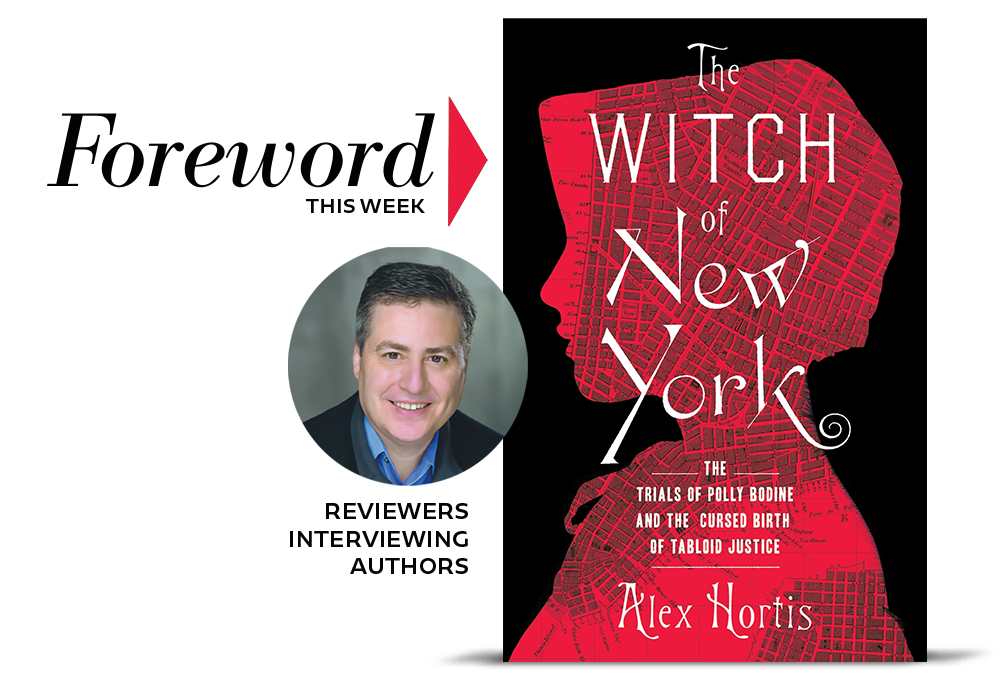

A Reviewer-Author Conversation with Alex Hortis, Author of The Witch of New York

“My personal epiphany as a writer came from this advice: think of your book as a movie in which you’re presenting scenes to the reader. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a vivid detail is worth a few hundred.’’ —Alex Hortis

This week we travel back to 1843 to hear the story of a horrific and sensational—yes, both—murder on Staten Island. Horrific, because the victims were a young mother and toddler beaten and burned to death on Christmas Eve, and sensational because the crime occurred just as the New York tabloids came of age as firebrands and propagandists, not only capable of reporting the news but shaping events for avid readers, as well.

In the 1840s, New York’s total newspaper circulation was already well over 100,000 and controlled by just six dailies: the Tribune, Herald, Sun, Express, Courier and Enquirer, and Journal of Commerce. They were the beneficiaries of great leaps in printing technology—from manual cranks to steam-powered rotary presses—that helped them increase output from 2,000 to 20,000 sheets an hour in a matter of years. Vastly cheaper to produce on these new presses, publishers were able to charge just a penny a copy, affordable for even the poorest of city folk.

And then, also in the 1840s, the telegraph arrived and changed the media landscape forever. Rather than waiting weeks for news from Europe or California, it suddenly arrived in minutes. (Honey, we shrunk the world.) But sending telegraphs was expensive, so most of the aforementioned papers, plus The Times, schemed to create the precursor to the Associated Press to offset the costs. With news by wire now a commodity, they effectively formed a monopoly.

Alright, let’s get to the double murder at hand. The lingering question is, whose hand? Was it Polly Bodine, the “witch of New York,” who killed her sister-in-law and eighteen-month old niece? Alex Hortis, author of The Witch of New York (review here), hints at an answer in his conversation with Meg Nola, below.

The 1843 murders of Polly Bodine’s sister-in-law and baby niece were exceptionally horrifying at the time. The crime was committed during the Christmas holiday season; it involved both bludgeoning and arson; and it was of course followed by an absurd media frenzy. When did you first learn about the case?

In 2014, I came across a 2000 New York Times article about the Polly Bodine case. I was intrigued. Edgar Allan Poe wrote about the case? P.T. Barnum made a wax effigy of her? As I researched the case, the story only became better and better. The sensationalistic reporting on the trials of Polly Bodine felt fresh and contemporary. So I decided to use the trials of Polly Bodine to comment on tabloid justice in our time.

Polly Bodine’s husband, Andrew, was an abusive alcoholic and eventual bigamist. Rather than live in misery, Polly left Andrew and had an affair with Manhattan apothecary George Waite. Polly’s refusal to stay with her husband—along with the affair, her reported abortions, and the stillbirth of George’s child while she was in jail—led to her public vilification. She also enjoyed an occasional “tumbler of gin” and didn’t seem to care if anyone saw her drinking in public. If Polly had been a church-going widow or an outwardly demure and younger woman, how do you think she would have been treated by the press?

Given the heinous nature of the crimes—a double murder of a mother and child over Christmas—the penny press would’ve viciously attacked any female defendant accused of the crimes. James Gordon Bennett, the unscrupulous editor of the New York Herald, reveled in misogynistic stereotypes.

If Polly had been a widow, the press might’ve portrayed her as a “black widow” killer who secretly poisoned her first husband, too. If she were an outwardly demure, younger woman, the press might’ve painted her as a duplicitous woman who held dark secrets (not unlike Lizzie Borden). Tabloid justice often caricatures the trial participants, including the accused, witnesses, and, sadly, even the victims.

The book contrasts 19th century Staten Island and Manhattan as culturally different places. Manhattan was considered to be the capitalist and morally corrupt “wicked city,” whereas Staten Island was more rural and close-knit. Yet the fishermen of Staten Island benefited economically from Manhattan’s voracious appetite for oysters, and the city’s vibrant energy surely had a certain intrigue for other Staten Island residents. Was Polly perhaps a bit entranced by the fact that George Waite was a Manhattan “sporting man?”

Polly seems to have been drawn to Manhattan. After she separated from her abusive husband, Polly started traveling into Manhattan, and worked as a shopkeeper in the city. When her son Albert became an apprentice to George Waite, she visited them regularly at Waite’s apothecary just off Broadway. “A feeling of the purest love, emphatically the purest love, sprang up between her and Waite,” represented Polly’s attorneys at trial. Beyond that, I can’t speculate on affairs of the heart. It couldn’t have been for his money. Waite was behind on the rent and even borrowed money from Polly’s father.

Polly’s family could afford to hire a “dream team” of defense attorneys, ably led by David Graham, Jr. If she’d been from a poorer family or simply on her own, what might have happened to her in terms of legal representation?

Without David Graham, Jr., I think Polly Bodine would’ve hung from the gallows. Graham was ahead of his time. He understood how the press could prejudice jury pools, and the need to reshape his client’s image in the courtroom. Remember, there was no public defender office in 1840s New York. (The New York legislature did not mandate court-appointed counsel for indigent defendants until 1881). Had Polly been from a poor family, she would’ve been lucky to secure any attorney admitted to practice. On occasion, Graham did take on pro bono clients in high-profile murder cases if he saw a sympathetic angle to the defendant. That might’ve been an indigent Polly’s only hope.

Polly’s three trials are recreated with captivating details, like how after hearing the Newburgh not guilty verdict, her supporters approvingly stomped their feet on the wooden courtroom floor. And there was James Decker, the “stubborn eccentric” holdout juror in Staten Island, who tried to escape further deliberations by crawling out of the courthouse window. The Jewish pawnbroker witnesses were subjected to ridiculously antisemitic courtroom theatrics, while the bevy of “gentleladies” who came to see the Manhattan trial arrived in a “sea of bonnets and dome-shaped skirts.” What was your research process to bring all this to life?

First, I’m so glad you enjoyed those details. My personal epiphany as a writer came from this advice: think of your book as a movie in which you’re presenting scenes to the reader. If a picture is worth a thousand words, then a vivid detail is worth a few hundred. My research gets obsessive: I try to find every piece of paper on the event, person, building, or weather. Then, I purposefully look for evocative details buried in those sources. For example, the newspapers described how Manhattan gentleladies treated the trial like gala theatre. So I researched 1840s fashion, and found a color sketch in a magazine of the “Fashions for March 1845,” the same month the trial began. Visiting the places where the events happened can be very helpful, too. The original courtroom where Polly was first tried has been remarkably well-preserved at Historic Richmond Town on Staten Island. I could see the height of the chandeliers, hear the wooden floors creak, and almost feel the drop that James Decker took from the window of the jury room to the ground.

Do you think Polly Bodine was guilty, or at least involved in the murders?

That’s a difficult question for a crime historian. Some authors believe that they should never reveal their personal views about a case, because it could interfere with the readers making up their own minds. To be clear, I did my best to present the best arguments and evidence for both sides. None of us were present in the courtrooms, and the Newburgh jury’s verdict was, of course, entitled to respect as a legal matter.

With those lawyerly caveats, yes, I am convinced that Polly Bodine was involved in the homicides. For me, the fact that Polly lied to her son Albert about where she was headed on Christmas night, and then wrote a note to George Waite trying to manufacture an alibi is quite damning. Even recognizing that the authorities used unduly suggestive techniques for the jailhouse identifications, there was little dispute that Emeline Houseman’s valuables were pawned by some woman on Christmas Day. It’s hard to see how any other woman would’ve even had access to Emeline’s valuables that morning. Without any evidence, Polly tried to blame a black family for the crimes, and urged her brother not to post a reward. Those seem like acts of a guilty person.

Now, the prosecution had an issue with proving first-degree murder with premeditation, because it couldn’t establish what happened leading up to it. Emeline had defensive wounds on her left arm, which strongly indicated a physical confrontation. Was that premeditated or spontaneous in the heat of a fight? It’s particularly horrifying to think of Polly coldly murdering her eighteen-month-old niece Ann Eliza. (The prosecution suggested that Polly killed her niece because the child was able to talk.) At the Manhattan trial, the jury asked if they could vote for manslaughter. If I found the prosecution witnesses as credible in person, I would’ve voted for manslaughter, and could have been persuaded to vote for second-degree murder.

Are you working on any new projects that you can share?

My next project is my most important one. My wife and I have an impossibly adorable five-month-old daughter named Sarafina. We love her so much. I am focused on raising her.

Meg Nola