"A work of photographic alchemy, Light Waves is an impressive collection"

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Craig Blacklock, Photographer of Light Waves: Abstract Photographs of Reflections from Lake Superior

Before every shutter click, photographers face the discouraging fact that capturing anything new in the world of photography is all but impossible.

As a professional nature photographer, Craig Blacklock confronts this reality everyday. His solution: showcase the familiar in new, innovative ways. And it was this approach that led him to create a technique for stunning abstract images of the world’s largest body of freshwater—exquisitely collected in Light Waves: Abstract Photographs of Reflections from Lake Superior.

Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland, himself raised on the northern shores of Lake Michigan, recently caught up with Craig to discuss the new book, environmentalism, the dangers of November gales, and more.

Lake Superior is an incomprehensibly positive force for our planet, and each of us who are blessed to know it benefit from the big lake in countless ways. Can you talk about how you got to know the lake?

I’ve known Superior my entire life. As a child, I lived 160 miles away, back before freeways. So getting there was nearly an all-day adventure with a much-anticipated reward at the end of the trip. Its massive size, with its crashing waves and horizon line stretching wide across my vision, was enthralling. Often, fog banks swept in, with their tendrils reaching up onto land. One of the rituals (no longer safe), was to drink the cold, clear water straight from the lake. Many of my most cherished childhood memories were formed on those trips, as well as my beginning to form a relationship with what would become the dominant subject of my life’s work.

I now live an hour from the lake, spending weeks each year kayaking its shores, but even with this intimate relationship, and forty-six years of photographing it, it remains exotic—partially veiled. Perhaps it is this, that continually drives me to find new ways to depict it. My earliest work showcased in The Lake Superior Images, depicted what it looked like. With A Voice Within: The Lake Superior Nudes, I expressed what it felt like to be within Superior’s environs. With Horizons and now with Light Waves, Superior has become a metaphor for things both personal and universal. I don’t title my images but hope that each viewer will discover their own connections and meanings within them.

The subtitle to your new book Light Waves, is Abstract Photographs of Reflections from Lake Superior. I know you have built your career around photographing the largest body of freshwater on the planet, and this series is no exception, but these photographs move well beyond the specifics of location—Superior is shown as a stand-in for our planet and what we are doing to it. The images are artworks that can be enjoyed by anyone, whether they know Lake Superior well, or have never heard of it.

Many of the photographs look like they could have been made with the new James Webb Space Telescope, a microscope, or an underwater camera revealing secrets from the depths of the ocean. That said, there’s something familiar about the images, but it’s like seeing the lake in a sidewards glance.

With Light Waves, you’ve transitioned to creating images that are a “glorious collaboration between light and water,” as expressed by Daile Kaplan in the book’s introduction, which seems pretty spot on. Please tell us about the evolution of creating Light Waves.

When I was born in 1954, the planet had nearly three billion people on it—already severely overpopulated. As a reference, many scientists feel the earth can only sustain a population of around two billion people if everyone is to enjoy a decent standard of living, and we allow areas of nature to thrive. By the time I was a teenager, many scientists and environmentalists were warning about rapid population growth and its ramifications. The planet will soon have eight billion people on it, and the warnings about climate change, water shortages, mass human migration, and species extinctions are now coming to fruition at an alarming pace. Climate-induced natural disasters (floods, drought, heat waves, wildfires, and intense hurricanes as we just witnessed with Ian) of the last few years culminated in a horrifying crescendo just as the pandemic hit.

I’ve always spoken and written about environmental issues, but while many of my peers turned their cameras towards the ugliness of the degradation, I continued to showcase the remaining beauty in the world, that more than ever, needed protection. By 2021 I realized I had to do something different with my art as well. I spent a lot of time during the pandemic lockdown thinking about what approach to take.

The overwhelming feeling I had, which I believe I shared with many, was that even familiar things seemed different—off. Even though my family remained healthy, and our own surroundings were intact, there was an overwhelming sense of imbalance and disorientation. Not just about the immediate pandemic, but the larger, slow-moving forces relentlessly altering our lives.

I incorporated that into my photography. Utilizing the same subject matter I had for decades—the wild shores of Lake Superior—but only showing it indirectly, reflected in the undulating waters of the lake itself. The light was my paint, the waves my brush, and my camera’s sensor my canvas.

In 2021 there were several forest fires near where I was working. The sky filled with smoke, and the sun remained a dull red disk well into the mornings. This created amazing photographs, but also tied the climate-driven fires directly to the art within Light Waves. I wrote an artist statement that served as a guide and summed up what I had set out to achieve.

“Light Waves is a response to the fracturing of our planet’s ecosystems at the dawn of the Anthropocene Epoch, simultaneously acknowledging changes and loss, while also revealing the beauty remaining to be discovered within the shards, providing a place of refuge.”

It was very important to me that this imagery remain beautiful. People need nature’s beauty to be whole, and even images of it can fulfill that need. So, while I am hoping this project helps raise awareness of what we are doing to our world, I am also hoping that people will find within these images, spaces they would like to occupy in their imaginations.

Please walk us, or paddle us, through the process of making the photographic images in Light Waves, from your planning to time on the water to shutter click to editing the images?

As a child, and throughout my life, I’ve been exposed to many styles of art, including the abstract art shown at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. Coming of age in the late 1960s, I absorbed a lot of influences that are only now fully finding their manifestation in my Light Waves series. There are two historic photographic series that I consider direct ancestors to my current work.

A century ago, Alfred Stieglitz turned his Graflex camera skyward, freeing images of clouds from the contextualizing anchor of land creating his Equivalents series, which many cite as the first abstract photographs.

Forty years later, Wynn Bullock created his groundbreaking series, Color Light Abstractions, with sweeping patterns reminiscent of Stieglitz’s Equivalents, but imbued with intense colors. Bullock’s subject matter was light, transmitted, refracted, and reflected through and from fractured glass and other materials arranged in his studio.

Now, utilizing advances in digital photography and editing technology, I’ve built upon these historic works, creating a fusion of the two. Like Stieglitz, I am photographing wind-driven patterns in nature, with Lake Superior supplanting Stieglitz’s clouds while embracing Bullock’s fascination with, and mastery of, color and light.

For this project, as in most of my past work, I’ve traveled by sea kayak to the wild shores of Lake Superior to find my subject matter. Trips ranged from a few days to nearly three weeks. My first trip specifically for this was to Isle Royale, the largest island in Superior. This was one of the trips with thick smoke, which helped create some fantastic images. But there were many more failures than successes, and I realized the technical difficulty in doing what I was trying to achieve. After that, I put together two hybrid camera systems that solved the most pressing technical challenge of getting a high magnification of the subject and getting it in focus.

From then on, I made about half of the images from my kayak, and the rest from a tripod-mounted camera on land. Viewing the saturated colors of Bullock’s Color Light Abstractions gave me permission to push the contrast and color saturation beyond what I would in my normal landscapes when I was editing the digital files. I realized that the larger they were printed, the more power they had. The inaugural exhibition of the series will be at the Palm Beach Photographic Centre’s museum, where many will be printed to around 40x55 inches.

Why do you believe the light-water collaboration you’ve captured is so compelling to human viewers?

It has been fascinating watching people experience this work and talking about it with them. There is a delight they take in knowing these otherworldly, abstract images are actually pretty straight photographs of nature. I’ve had several people say they don’t normally like abstract art, but they love these. I think it is because they don’t have to worry about what it is. Just knowing it is a reflection of something real allows them to get past that impediment, and lets their imagination take over in how they enter and relate to the images.

We also are drawn to familiar things shown to us in new ways. In the world of photography, finding anything new is nearly impossible, but as far as I’m aware, nobody has done anything quite like this.

Working with the Minnesota Land Trust and other organizations, you’ve helped preserve undeveloped shorelines and make them accessible to the public. Warming lake temperatures caused by global warming, as well as invasive species like gobies, zebra mussels, sea lampreys, and a couple others are changing the lake. What have you noticed over your decades of hyper close observation? What encourages you? What worries you?

Of course the invasive species with by far the largest impact is us, humans. During my lifetime I’ve seen much of Superior’s shoreline, especially on the US side, transition from wild to a strip city of cabins and mansions. Even those rich enough to own such properties no longer have access to the beauty they usurped—it’s gone. Also gone is the chance to hike or pull a boat up on those shorelines without running into no trespassing signs.

Regarding climate change, there are areas that used to freeze over every year, allowing access over the ice to places like sea caves with icicles draped over their arched openings. Now our winters are warmer, and the ice less predictable. Those warming waters, along with invasive species, are also threatening some of the most important fish species.

My daughter is a senior at the University of Minnesota, Duluth, with a double major in art and environmental sustainability. I am encouraged by her generation realizing they must take personal responsibility and make personal sacrifices in order to save our planet. What worries me is that by the time they take charge, our generation’s failures to act may have already diminished their prospects beyond hope.

With an eye on Africa, the Middle East, America’s West, and other water stressed areas, those of us who live in the Great Lakes basin can’t help but feel a level of comfort. Even so, water rights, water wars, water anxiety will be a major factor for all of us on this earth for the foreseeable future. Where is your head on the topic?

In the coming decades, there will be over two billion climate refugees seeking cooler areas with access to water. This is going to put huge stress on the environment and quality of life in regions like the areas around Lake Superior. It all goes back to overpopulation. Our best hope is that while we humanely assist in that migration, we have the love and wisdom to lower our birth rate, eventually reducing our population down to the carrying capacity of a damaged planet. Realistically, that may be less than 1.5 billion.

We happen to be corresponding as the Gordon Lightfoot “gales of November” season approaches—and, no doubt, you have a story or two about how the lake kicked up unexpectedly and caught you unawares. Care to share? Did you ever lose an expensive lens overboard?

Lake Superior of course can produce waves large enough to sink huge ships. A trained kayaker in good shape can navigate quite large waves. As I often say, “it is landing that kills you.” Part of the responsibility of being a safe paddler is planning your route so if bad weather comes up, you know where the closest place to land safely is. There are many areas where it is miles between safe landing options, so getting good weather reports ahead of launching your boat is important.

I’m a pretty good paddler, and at 68, still in great shape. I’m also a prudent paddler and know when to get off the lake. In thousands of miles of kayaking, I’ve only tipped once, when my bow caught the lake bottom as I was approaching a beach in heavy surf. I was in a dry suit and comfortably walked my boat to shore, and no equipment was damaged. I’ve lost one light meter and one camera over the years, but both while I was walking along the shore, not paddling!

And lastly, what’s your next challenge? What are you currently working on?

I plan to continue with the Light Waves series. I’ve done some experimenting with a bit more freedom in editing the images, and I’d like to see where that might take me.

I’d also like to do a second edition of my first large book, The Lake Superior Images. That was all shot on large or medium format film, which had many limitations compared to what can be done with digital cameras, not to mention that I now also do much of my photography using a drone-mounted camera.

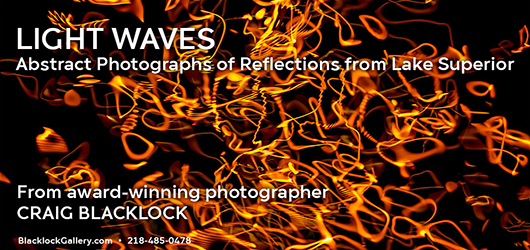

Light Waves: Abstract Photographs of Reflections from Lake Superior

Daile Kaplan

Craig Blacklock, Photographer

Blacklock Photography Gallery (Nov 18, 2022)

A work of photographic alchemy, Light Waves is an impressive collection that showcases the dramatic, shifting natural wonder that is Lake Superior.

Years of kayaking along the shores of Lake Superior, sometimes for weeks at a time, are distilled in Craig Blacklock’s latest collection of abstract landscape images. Published in conjunction with an exhibition of digital prints at the Palm Beach Photographic Centre, Light Waves features an emotive series of portraits of the lake’s ever-changing surface.

In her introductory essay, photography historian and critic Daile Kaplan describes Blacklock’s long career as a landscape photographer and environmental champion, setting his long and shifting career in the context of other iconic artists who feature natural landscapes in a variety of media and through other historical eras. She also chronicles his transitions between color photography, large-format black-and-white photography, and digital photography, highlighting his mastery at manipulating color, light, and form through “an artisanal approach to digital printing.”

In previous collections Blacklock shot more descriptive depictions of wildlife, shorelines, and water, whereas Light Waves features “extracted images” that are abstractions of the interactions of atmosphere and water. They convey a range of powerful emotions. Some are calm and playful, while other photographs pulse with the nervous energy of angry colors and jagged patterns.

Kaplan notes that Lake Superior has the largest surface area of any lake in the world and that this watery leviathan contains huge amounts of the earth’s freshwater reserves. But despite its vast volume, depths, and lengthy embrace of Minnesota, Michigan, and Ontario, Kaplan also says that this great body of water is showing the effects of climate change: its waters have warmed, and the winds over it have grown more fierce. Blacklock’s photographs evince these dramatic changes. Some images radiate with volatile energy and unusual colors; many are streaked with slashes of neon orange and red, refracted from skies laden with ash from intensified local wildfires.

Many images form contrasting pairs, while others are featured as singles or in triptychs. There are softer patterns of closeup shots, and other images that display more intricate and dramatic compositions shot from a distance. Blacklock’s exploration of how ripples on Lake Superior’s watery skin can seem like other surfaces is photographic alchemy. Water becomes sky becomes earth and rock as the pages turn.

Reflections from shoreline greenery in some images make Superior’s surface seem less like water than slices of agate or malachite. The electric blues and golds of another image are akin to the contents of a metallurgist’s cauldron. A calming symphony of hazy gray stripes in one image contrasts with its neighbor—a torrid composition that appears like something solid, bathed in red lacquer. One could be forgiven for mistaking aqueous surfaces for textiles, light sculptures, or calligraphic scrolls.

The sleek book design and judicious use of white space that balances and frames each suite of images complement the subject matter. Some words from the artist describing these artworks and his new creative direction would be welcome, though.

Light Waves is an impressive photographic collection that showcases the dramatic, shifting natural wonder that is Lake Superior. It shows an artist at the height of his maturity, dazzling audiences with images of impressive skill and sensibility. Above all, it is a testament to Blacklock’s lifelong “spiritual connection to the lake.”

Rachel Jagareski (October 31, 2022)

Matt Sutherland