America's Last Wild Place: A Love Letter

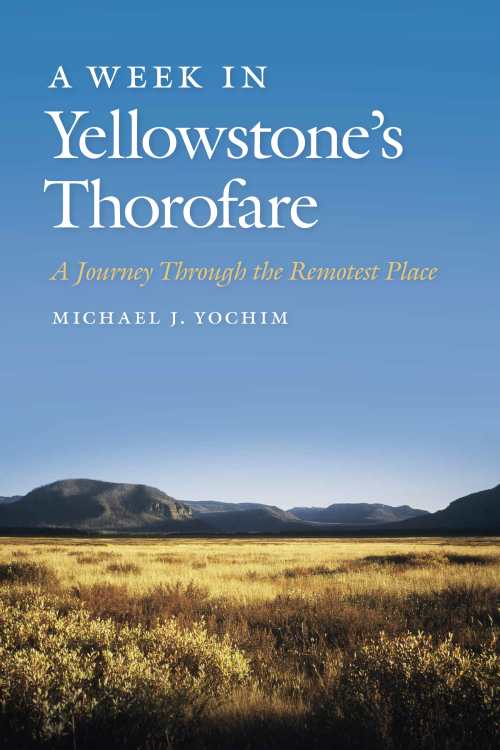

It’s been 100 years since the creation of the National Park Service, and one of the United States’ most iconic parks is Yellowstone. If Yellowstone National Park had a voice, it would be that of Michael J. Yochim, author of a series of books about the park, including his latest, A Week in Yellowstone’s Thorofare: A Journey Through the Remotest Place (Oregon State University Press), released in June.

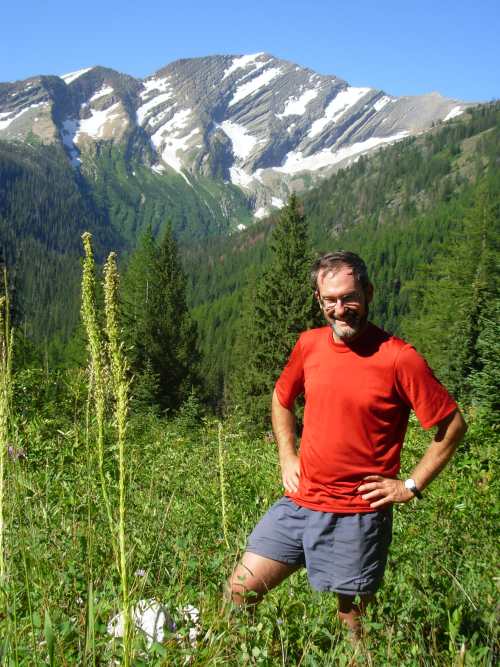

What makes Yochim’s voice particularly powerful is that he is not a tourist. He’s not a writer who came to Yellowstone just to write about it, then leave. Yochim knows the wilderness well, having worked more than two decades as a park planner. His passion for the beauty and preservation of one of the last wild places in the country shows. This is likely Yochim’s last word on the subject, though. He has been diagnosed with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS), and he’ll lose the ability to walk, talk, and take care of himself.

Yochim kindly granted me an interview despite his condition, and his responses show that he has not lost his eloquence and passion.

Do we need to choose between human development and wilderness? Or can we really have both in the long term?

Michael J. Yochim: 'It's also about taking personal responsibility for what we do when we're in nature.'

Development and wilderness protection are not part of a zero-sum game. With 7.4 billion of us on the planet already, and 9 billion expected by 2050, we have little choice about whether to develop. It’s how we develop that is crucial; do we sprawl, as we have done in so many parts of the country, or do we adopt smart growth practices? Things like infill development, zoning for more livable communities, and redevelopment can provide for a growing population while preserving farmland and open space.

But it’s more than just being smart about how we develop, it’s also about taking personal responsibility for what we do when we’re in nature (especially in wilderness), just as we do in our communities.

As I wrote in my book, wilderness can’t be all things to all people. Wilderness is about restraint, from that which we exercise when we set it aside, to that which we exercise when we’re in it, from following Leave No Trace principles to refraining from activities prohibited in wilderness, such as mountain biking or snowmobiling. It’s about recognizing that if we limit our personal freedom, we gain a societal freedom, a place for everyone to escape, to find beauty, to experience wildness, to share with others we love.

As your ALS takes its toll, this book will become your voice on this topic. What is the one thing you hope readers will take away?

That, no matter who or where we are, wild places are incredibly important as a source of inspiration for us. We all need inspiration occasionally. Most of us will never visit the Thorofare, but many of us will find inspiration from knowing that a place almost twenty miles from a road still exists in our country, outside of Alaska.

Others will take comfort in knowing there are still places that humankind has not altered, that still bear the imprint of whatever creator they believe in. Some will find solace in the fact that there are still blank spaces on the map, places they can explore and experience the sense of discovery that our forefathers and mothers found.

Some will be relieved to know that true silence can still be had, that nature’s sounds still dominate somewhere. Others will cherish the fact that wildness can still be found, the visceral feeling that forces more powerful than us still bring a touch of fear and mystery to us. Still others will take joy in knowing that there are places where the furry and feathered creatures we share the Earth with find a home and roam freely. Some will smile at the beauty of wild places, beauty that we can only hope to replicate in our works. Others will dream of the day when they can escape from their reality to find a different, more basic reality.

Whatever the reason, wild places carry rich rewards, inspiration that is not always available from other sources.

It has been 100 years since the creation of the National Park Service. What will Yellowstone be like 100 years from now?

Yellowstone National Park is forty-four years older than the NPS, and if there is anything we’ve learned since 1872, it’s that the park is always changing, ever resilient, and endlessly fascinating. We have never stopped creating Yellowstone, and its meanings have been constantly evolving. That is almost certain to be the case in another century, but there are some changes we can expect to see. One of those is that its visitors will be more diverse, reflecting the increasing diversity of Americans in general. Another change is that the modes of transportation will have evolved, as they have been throughout the park’s existence.

As for the park itself, it’s anyone’s guess what it will look like, depending mainly on whether we get serious about addressing global warming. If we do, Yellowstone may look much the same. Although changes have already begun, stabilizing carbon emissions will keep those changes to a minimum. If, on the other hand, we persist in our intransigence and denial of the reality and risks of climate change, there will likely be dramatic changes in the park’s biota, as the effects of global warming become widespread and all-encompassing.

I discuss some of the possible changes in the book, so here I will sum them up by stating that the park will be a very different place ecologically, with uncertain and varying effects on the wildlife species that call Yellowstone home. Our most beloved national park may well be radically and irrevocably altered by the very society farsighted enough to protect it for everyone—and its ability to inspire may follow the same trajectory.

Howard Lovy is executive editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow him on Twitter @Howard_Lovy

Howard Lovy