An Interview With Deepak Unnikrishnan, Winner of New Immigrant Writing Prize

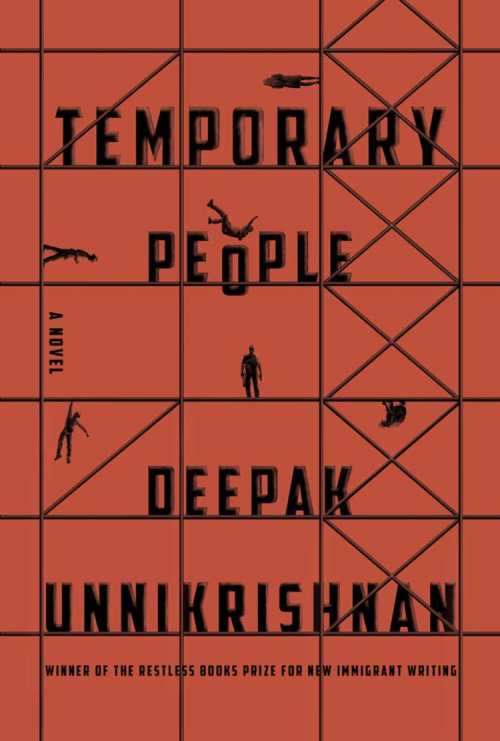

Ann Arbor is gray and drizzly for Deepak Unnikrishnan’s first visit. Fresh from stops on both coasts, the New York/Abu Dhabi-based writer asks the timezone and sets his watch as we sit down. His first book, Temporary People, was published by Brooklyn-based Restless Books in March and is the inaugural winner of its Restless Books Prize for New Immigrant Writing. The collection brings together guest workers’ voices in the United Arab Emirates to explore nationality, impermanence, and the Gulf. This interview has been shortened and condensed.

How did you come to this project?

Deepak Unnikrishnan: 'One of the most tolerant and diverse places on earth that I inhabit is in the Middle East.'

I’ve been thinking about it for ten, twelve years. I’ve lost track. I think sometime midway through the process, while I was here in the States, I started reading narratives of the Gulf. I didn’t come up with much in English. Wilfred Thesiger’s Arabian Sands is a good one, Cities of Salt by Abdelrahman Munif is an excellent one as well. Then I looked at Western reportage about the Gulf, and it was always skewed in the direction of labor—labor was the be-all and end-all.

My parents have lived there for quite a while and I didn’t see much about them, so I was contemplating what else could be said or written about the place, written about the children of the place. I also understood that I wanted to play with architecture, form, and language—not just English but variations of it, how it’s spoken in the Gulf, and use semblances of Hindi or Malayalam because I felt if I left them out then the place wouldn’t register properly with me as a writer.

I think by that stage I’d realized that’s what was missing from narratives of the Gulf; I didn’t know what the place sounded like, especially Abu Dhabi. Everything I’d read up to that point at least in English didn’t have that register.

How do the stories resonate for you as a whole?

Not only did I want the stories to speak to each other, I also wanted the stories to separate. if you wanted to think of it as a collection, you can. I was asked whether it’s a novel, and it’s very gracious when people consider that, but I don’t think it is. There’s a conversation being made and I think that’s necessary for what the book is trying to do. I don’t think even the book knows what it is: it’s trying to be something and it doesn’t know exactly what it is.

The book to me is also a consequence of circumstance, what I’ve become, what the city made me into, what the cities made me into—Abu Dhabi, New York, Chicago—and I wanted all of that. I wanted someone to pick up the book, look at it, and go, “What is this?” I’d prefer conversation rather than someone going, “Ah-ha! Here’s the how-to manual on what the Gulf is.”

What was it like to work with Restless Books?

Fantastic. Anna Ghosh, my tenacious and wonderful agent, sent me an email in the fall of 2015 saying there’s this prize, it’s inaugural, and it’s a publisher called Restless Books. It was gratifying to see they were looking for a certain kind of content, which resonated with me mainly because of my background. In early 2016 I got an email saying I’d won it. Once I met them for the first time, they started asking me about the relationship between the pieces and why I did what I did.

We had a very long conversation about language, and I told them I don’t have many conditions; no one knows who I am and you’re willing to publish me, so forgive me, but I do not want to italicize anything. It’s not that these languages are foreign, they’re English as well. This is written by someone who’s acknowledging or paying homage to them, not only that but using them. I wanted that to remain. And they said, “Okay.” That wasn’t what I had expected. They’re very gracious and generous and I’m grateful.

How does your work tackle the subject of migration or societal conflicts around migration?

For me, what’s missing in the word today is just f—ing kindness. If someone had told me the book would come out in a time when Donald Trump was president, that would have felt more surreal than the book itself. If the reader picks up the book and says, “Here’s someone who’s a migrant who doesn’t identify as a national of any country but who identifies as a creature of cities that raised him, what does he think?” That might be useful.

If we are indeed living in a world where citizens are global citizens, we need to grapple with what that means. Can we forgo nationality? I hope the reader thinks about that, and I hope they don’t think about anything at all because at the end of the day the response to the book is anything the reader wants it to be. I’ve been writing about the Gulf for a while and few people were interested. All of a sudden, they are. I’m interested in why people matter, why they matter when they matter.

Is there anything US policy or people in the United States can take from the UAE?

You’re talking about a nation where 80 percent of folks are from other places. People figure out a way to live together or tolerate each other. On top of that, when you have a country that’s evolved so quickly the way it has, problems amplify over time. It’s not the perfect system, but at this point one of the most tolerant and diverse places on earth that I inhabit is in the Middle East.

I say the Middle East and people assume certain things—I’m pretty sure someone is thinking of one tank, one bomb, one gold-plated Ferrari, something. They’re not thinking of tolerance, of conversation, of arguments respectfully stated across the table. I live in a country like that. I thought I could say the same years ago about not just the US but also North America or maybe even Europe, but I can’t anymore. Something is broken and needs to be acknowledged.

Everyone says look West. Maybe we should look East and West and North and South and take bits and pieces of whatever works and try to do something with the world and not screw it up.

Rebecca Huffman is a freelance writer and editor based in Ann Arbor, Michigan

Rebecca Huffman