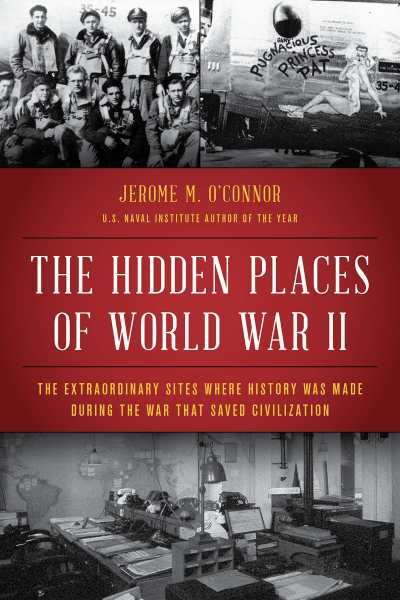

An Interview with Jerome M. O’Connor, Author of The Hidden Places of WWII: The Extraordinary Sites Where History was Made During the War that Saved Civilization

Let’s take a moment to look back at the twentieth century in order to appreciate the stunning changes wrought by the two great wars. “Appreciate” may be the wrong word in solemn remembrance of the Holocaust, but from the standpoint of politics, culture, nation states, and mind-boggling loss of life and treasure, WWI and WWII (scholars now consider the two just one war with a long, tenuous truce in the middle) changed virtually every region of the planet—and thankfully ridded the world of that idiot Hitler.

Next year, 2020, will mark the 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War. All of the men and women who fought and served in the military during the war are now in their nonagenarian and centenarian years and approaching their final, unwinnable battle with mortality. Aside from that sad fact, tens of thousands of WWII books and hundreds more movies have been released detailing seemingly every battle and nuance of the war. And more books and movies keep coming. Are we world warred out?

This week we welcome Jerome O’Connor, an accomplished historian who believes that much more coverage of the war is warranted “because of the vastness of the war.” The new author of The Hidden Places of WWII, O’Connor explains his motivation to write and research by saying, “Instead of further opening an already existing seam of knowledge, I would change course completely and describe the people, places, and events that were all but ignored by history and other writers. Even better, most would be unknown and unrevealed.” And, we’d add, compelling to hear about as only top quality military nonfiction can be.

Melissa Wuske reviewed the book enthusiastically in the March/April issue of Foreword Reviews. With an assist from the good people at Lyons Press, we connected Melissa and Jerome and the rest, yes, is history.

Take it from here, Melissa.

Much has been written about World War II—that’s certainly an understatement—and yet somehow there’s still more to say about this pivotal era in the twentieth century. And indeed, you’ve added a vital and needed book to the canon. How do you explain this need for another World War II book? And why this one?

It may reasonably be asked: Why another book about WWII? How many ways and times can the Battle of Guadalcanal, for example, be retold, or can any land or sea battle be described still again? That’s the question I also asked myself in 2016 when, after fifty-two years of journalism, I decided to write a book with an entirely different insight into the war.

Instead of further opening an already existing seam of knowledge, I would change course completely and describe the people, places, and events that were all but ignored by history and other writers. Even better, most would be unknown and unrevealed. To qualify, every event, place, or person had to be not only factual but had to exist, even if in remnants. The book, therefore, mostly describes what was not previously known, and may thus add a few pages to history. It actually enters the real places forgotten by history, although it took half a century for them to be accumulated.

This book focuses on “little-known, overlooked, or under-reported people, places, and great events of modern history,” as you describe on your website. Why do you think certain significant events, places, or people fall into the shadows? Or, looking from the other direction, why do other events, places, or people dominate the narrative memory of a culture, sometimes holding a disproportionate share of attention?

Let’s first take the example of Bill O’Reilly’s current Killing the SS. It’s another in the undeniably successful series that began with Killing Jesus. In considerable detail, he describes the well-known evil personages who carried out the mass murders of the Jews of Europe. One of them, in fact, the architect of the Holocaust, Adolf Eichmann, has pride of place in the narrative, but no mention of the suburban Berlin locale where the decision was made to conduct the “final solution.”

In chapter twenty-two of my book, a section called “Wannsee—The House on the Lake” brings readers through description and photos into the very same place—and in much its original appearance—where the decision was made, the meeting notes taken by Eichmann, who then carried out the mass murders. I place decision-makers in the same place where others—and this is no criticism—begin their narrative later, and, perhaps, also predictably. Bill O’Reilly and many others avoid the actual places that still exist or perhaps concluded that they were destroyed or were not even real.

Why do people and events “fall into the shadows?” For there to be shadows, there must first be prior existence. In much of the book, I describe people, places, and events for which no prior knowledge or shadow exists. They remain unknown. Because of the vastness of the war, I propose that much more remains to be revealed, especially as the 75th anniversary of its end approaches. It will be an international observance across all media platforms, and the last hurrah for the fighters who will all be gone at the centennial observance. The book’s epilogue honors their sacrifice while some are still here to accept the honor.

You’ve done significant research and reporting for many years about the World War Two era. What captivates you about this time period?

Most of the twentieth century involved preparing for war, conducting war, or rebuilding after the wars. Yet, only two of those wars (WWI and WWII) were declared by the United States, both under highly extenuating circumstances. Along with the founding of the country and the Civil War, the Second World War (a continuation of the first) utterly changed almost every people, culture, empire, country, and previous borders everywhere. WWII easily ranks as among the few most important events in American history. Only America—a country torn by pre-war isolationism, factionalism, cultural and ideological divisions, and possessing at best a third-rate military—survived intact. Those on the home front, who also won the war, and the military brought about a never-before-possible and never-again-to-be-repeated victory that defines the country to the present day. It was a once-only event in all history, and I was around as a child to absorb some of it on the home front.

I also recall that our immigrant block in the Englewood neighborhood of Chicago’s South Side echoed with the emptiness of all the young men gone to war—about seven boys for every block in Chicago and the other major cities. I remember the blue banners that meant a family member had gone to war, and one house with a Gold Star in front of the white linen curtain. The family in that bungalow had a son or brother who would never return.

I knew that a war was underway, but it would take decades to know its significance as the war that defined the entire century and made America the world’s dominant power. For me, it later became almost natural to find and report on places where some of the great events of that war were discussed or decided. The best history is the history that lives, is real, and can be seen, walked, and often entered.

Was there a moment in your travel, research, or writing of this book that stopped you in your tracks—with wonder, grief, overwhelm, confusion, or something else?

What not only stopped me but brought me to my knees happened at one of the long-gone USAAF bases in England from where thousands of attacks were launched against Nazi Germany. The young men knew that they flew against the odds and that every mission successfully finished meant that the odds of completing the minimum number of missions—first 25, then 30, then 35—meant that the odds of returning from the next mission dramatically increased. Yet they flew and had ten times the casualties of the infantry, who had at least a semblance of control over their lives on the battlefield that the airmen lacked. They flew from A to B.

With that as background, on my final day exploring the remnants of the Eighth Air Force base at Old Buckenham, where Jimmy Stewart was stationed, I encountered an area near the runway with visible bicycle tire tracks, then initials from long ago in the curing concrete, and then size nine shoe prints defiantly trailing into the distance. And it did bring me to my knees as my hands traced the initials from those kids who flew perhaps into eternity. Who were they? I wondered. And by what resolve were they able to go up again and again? I concluded that they went up for each other as much as for the desire to rid Europe of fascism.

What lessons does the war hold for modern America—personally for citizens and nationally in international affairs?

As made clear in the introduction, the two wars were really one great war separated by an uneasy and vengeful truce. The victors in the first war, mostly France and Britain, were determined to reduce Germany to near indigence through reparations, making certain the rise and success of the demagogue who ensnared Europe’s most progressive country. Beware demagogues in America and everywhere. The lessons for the future include maintaining a strong military and, most especially, not withdrawing from the world through a new isolationism some would call “America First,” exactly the rhetoric that nearly fatally divided America in the 1930s.

Your research has involved significant travel to see the sites firsthand. What are some practical tips for more casual travelers for seeing the depths of history in the places they visit?

Prepare by reading and researching every possible aspect of the planned trip. Develop an itinerary and assume that more time will almost certainly be needed. Rent a car. Establish a research base and visit the museums in the area for maps and assistance at local travel offices, even libraries. They are eager to share information.

Melissa Wuske