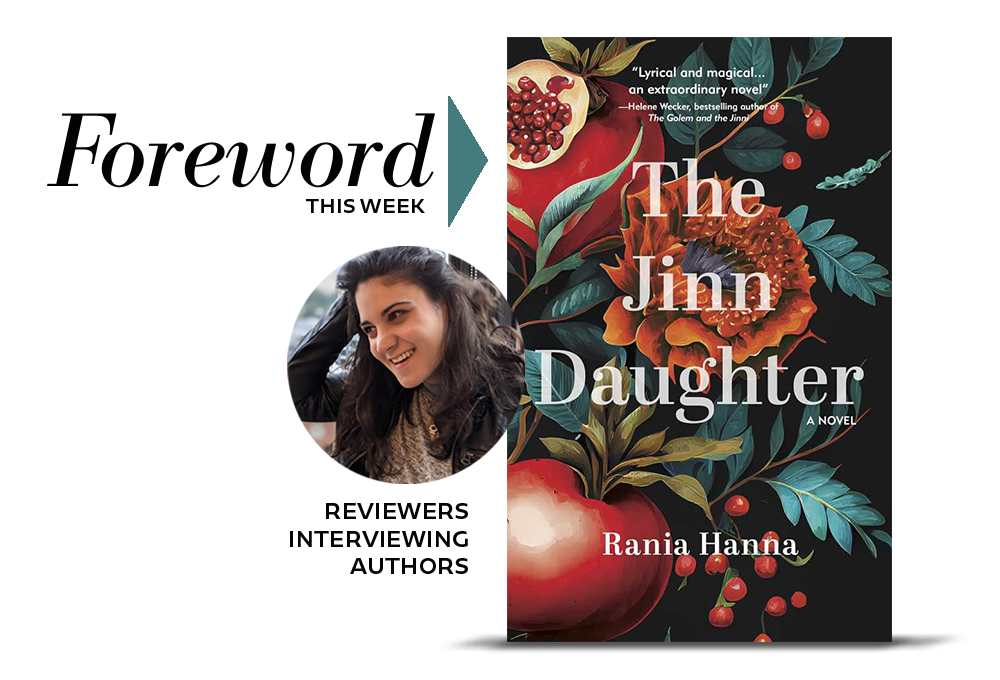

An Interview with Rania Hanna, Author of The Jinn Daughter - Foreword This Week

“Being a Jinn is something Nadine is proud of, but she is also fearful because of how she is treated. This is something that parallels, I think, to many immigrants and children of immigrants. People have a pride for who they are, where they came from, and where they have gone, but there is a wariness of being afraid to be seen as something different or less than because of an accent or the color of skin or their ‘foreign’ name.’’ —Rania Hanna

Snow White, Cinderella, Rapunzel, Red Riding Hood, and other folk tale heroines from Europe’s deep past were subject to all manner of sexual and violent trauma as their stories were originally told. Indeed, there were such horrifying depictions of sex and violence that Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm blushed and took out the worst of it when they compiled their magisterial Grimm’s Fairy Tales in 1812. But the sage storytellers of old also understood something about the minds of youngsters that many contemporary parents overlook. The Brothers Grimm didn’t sanitize the stories too much because they knew that the violence, sexual references, and chaos of fairy tales helps kids deal with their own inexpressible, inner-life dilemmas.

The metaphors buried within the tales are true and helpful precisely because they aren’t real.

By being overly protective, scholars warn, parents don’t let their children see that much of what goes wrong in life happens because humans aren’t perfect—and very often, it’s displays of selfishness or aggressiveness or anger that is to blame for our own problems.

Today we’re excited to spend time with Rania Hanna, a modern-day fabulist who certainly understands the great appeal of storytelling to wrestle with parenting’s grandest dilemmas. In The Jinn Daughter, Rania explores just how far a mother will go to rescue her daughter from death.

Along with starring her review of Jinn in Foreword, Karen Rigby jumped at the chance to fire a few questions at Rania.

The Jinn Daughter explores Nadine’s desire to protect her daughter, Layala. At what point do you feel that love might threaten to overwhelm, or create misunderstanding? It’s striking how a mother can be driven by her own ideas about what seems best …

I think any parent or caregiver behaves in this way. Layala is about fourteen years old—she’s young to be making decisions that would affect her the rest of her life, when her mother, Nadine, knows what’s best based on her experience dealing with death as a realm and Death as a goddess. I think Nadine is behaving in good faith and trying her best as a single parent, who is ostracized by society and wants better for her daughter. Of course, we see that doesn’t work out the way she wants, and ultimately, she loses control of the situation. But I think Nadine grows as a character by the end of the novel.

Amid the fantasy setting, was it a conscious decision to portray mother-daughter relationships in as realistic a manner as possible? Did any aspect of writing about these characters surprise you?

It wasn’t necessarily conscious—it’s more that the relationship unfolded this way. I initially wanted the story to be more about Layala, but Nadine took over and it seemed that this was her story to tell, not Layala’s, and I gave her that space. Some of the dynamics grew out of my own childhood and adolescence, and the tensions that are born simply out of people living together as a family in a shared space. I’m not a mother, so I don’t know what it is like being a mother, but I can imagine the fears and worries Nadine has as a parent, thinking back to my relationship with my own mother.

Death is a mother here, with her own yearning, too. She’s made more than only an adversary because of it. Would you speak about the myths, stories, or inspirations behind her?

Death as a goddess, and as a mother, was born out of parallels to Nadine. Kamuna (Death) grew into her role as a nurturer, partially because I did not want her simply to be a power-hungry goddess. She needed to have a reason for wanting the things she does, and she needed to have a driving factor for eventually accepting things. I don’t know that I necessarily pulled from specific myths or stories, but I do love books like Sabriel by Garth Nix, which focuses on death as a realm. I wanted death to be incarnate, and Kamuna grew out of that desire. At the core, I wanted to humanize death, since it’s such a central piece of the narrative.

Inherited legacies provide both a comforting path to take pride in, and a weight. How does being a Jinn, who is never far from learning about what has happened to others, shape or change Nadine?

Being a Jinn is something Nadine is proud of, but she is also fearful of because of how she is treated. This is something that parallels, I think, to many immigrants and children of immigrants. People have a pride for who they are, where they came from, and where they have gone, but there is a wariness of being afraid to be seen as something different or less than because of an accent or the color of skin or their “foreign” name. Nadine has these same experiences, and though she was born in the land she is ostracized in, she is seen as different, and because of that difference, she is hurt. But she is proud of her heritage, and her magical inheritance, even as she knows it can put her and her child in danger. It’s a thoughtful balance she has to strike every day.

Stories play a strong role: the stories of others, stories as morals or fables, even the subtle stories people might be tempted to tell themselves to make their actions seem reasonable. When did you know that the novel would take its current form, as a collection of many stories?

From the start. I wanted this narrative to be like One Thousand and One Nights, where there are smaller stories interwoven into the larger narrative. Some of the stories are actually ones, or based on ones, that my father told me growing up! So those are special for me, and many of the others I made up based on a swirl of fables I read or heard growing up. Fairy tales are such an integral part of so many childhoods, and they provide such a magic as we grow up, and I wanted that feeling in this book.

Sacrifice, and the wisdom of the young, are compelling themes. Was Layala’s decision planned from the outset, or did you discover, as her author, facets of her character along the way that made leading her seem inevitable?

It was a mix. I did want her story to end somewhat the way it did, but I didn’t know how that would happen. I trusted her to make the decisions she needed to to get to the end of her story. I did wonder if at some point Layala’s story ending would actually be Nadine’s, because I did want Nadine to make an ultimate sacrifice. But with Layala taking the lead at times, and Nadine making a sacrifice, just not the one I thought she would, the story came together the way it did.

Karen Rigby