An Interview with Sally Cole-Misch, Author of The Best Part of Us

To enter the novelist’s realm, writers must travel a path with countless forks, switchbacks, and deadends—a veritable maze leading to the glorious moment a finished manuscript is shipped off to a publisher. The editorial team at Foreword Reviews is always interested to know the backstory behind these journeys. Who are these people and what was it that compelled them to spend months and years in the brutally difficult act of writing?

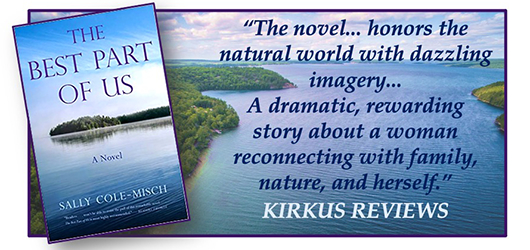

In the case of Sally Cole-Misch’s wonderful new novel, The Best Part of Us, the answer is crystal clear: an environmental educator with a degree in journalism, Sally seeks to inspire readers to connect with nature as a means to discover something larger than themselves. What could be more needed in these times of pandemic and increasing perils of a warming planet?

We recently caught up with Sally to learn more about her considerable storytelling skills and environmental convictions. She was all too happy to oblige.

You open the book with a scene in which Beth faces bittersweet memories of her edenic childhood summers spent on a remote Canadian island, along with the realization that she alone has been given the power by her grandfather to decide who will inherit the family cottage. Can we assume you know how to make a mean wild blueberry cobbler and that you’re comfortable trolling for whitefish and lake trout in cold northern lakes? How does that early nature experience influence who you are as an adult?

When I first learned to write fiction, my professors emphasized picking one element—setting, character, or plot— that is familiar to ground the story. So yes, this setting was an easy pick as my familiar piece. Cobbler, pie, pancakes, I’ve probably made everything possible with blueberries! I’m also fortunate to know the essentials of trolling and the rush of adrenaline from jumping into one of the northern Great Lakes region’s deep, clear, and cold lakes. Beyond that personal connection, however, Beth took over the story early in the writing process for The Best Part of Us and created her own unique experiences, settings, and family. Letting the characters lead the plot in unexpected directions was fun and exciting.

My early nature experiences must have seeped deep into my pores, because I’ve spent most of my career in environmental communications and my family vacations in the outdoors. In the early days of environmental protection, we thought we had to hammer home all the horrible ways humans were destroying our air, water, and soil. We realized fairly quickly that negative information doesn’t encourage personal change, and switched our focus to connecting with nature first, because what people value, they will act to protect. The benefits of spending time in nature are well documented in hundreds of studies: it feeds the soul, reduces stress, makes us more aware of the world around us as well as within, and gives us a sense of generosity and commitment to something larger than ourselves.

Summers on Lake Wigwakobi exposed Beth to entrenched tension between Indigenous, First Nations landowners on one end of the lake and her grandfather, a first generation Welsh, who bought the land in the 1940s and flatly rejects any idea of Ojibwe cultural heritage. Beth, her siblings, and even her parents are quite sensitive to the Indigenous cause, to the great dismay of Taid, their grandfather. Please talk about this aspect of the story and how you came to be so aware of these issues?

I’ve had the good fortune to learn about Ojibwe traditions, structures and land conflicts from members of several US tribes and Canadian First Nations in my work. Both countries have long histories of taking land from Indigenous peoples who had lived on it for thousands of years, even after treaties and agreements, and resolving many of those conflicts continues today. I also learned that their spirituality and culture focus on Mother Nature, our collective role as part of nature, and celebrating her many gifts to our lives, which reflect the novel’s key messages and themes. For these reasons, as well as that Ojibwe still live throughout the northern Great Lakes region where the novel is based, I couldn’t imagine writing this novel without including them.

Beth’s older sister, Maegan, and brother, Dylan, each contribute to a spirited triangle of siblings. And her parent’s political persuasions and intelligence make for lively family conversations. As the youngest, Beth is vulnerable, often feels left out, and experiences severe anxiety which she deals with in different, sometimes self-destructive ways. These relationships drive the story. Was the complex sibling-parent dynamic a main focus for you as you worked on the novel? Where did you look for guidance and inspiration?

When I first thought about who should be in Beth’s family, I wanted to include three generations for the varying dynamics of discipline and affection that can occur between and among them. I also considered each character in terms of their innate level of connection with nature—from the Ojibwe, Ben, Dylan, and Beth on one end of the scale, the grandparents and Evan in the middle, and Maegan and Kate on the other end. How would that connection drive their thoughts, motivations, and actions throughout the story, as well as their perspectives of each other?

Finally, I focused on each character’s personal sense of loyalty to her or himself, which I view as a sort of coming of age we all go through as we travel through life. How might each character come of age over the course of the story in terms of what and who they are loyal to, and how do these conflict with other family members’ viewpoints and priorities? These three elements for each character provided plenty of opportunities for complex sibling and parent dynamics.

I also wanted to try to write a story where every character had the best of intentions, based on their own needs and wants but also based on their deep love for each other and the island. Collectively their actions resulted in unintended consequences and outcomes, which each person has to deal with individually. Will they consider their actions and learn from them, or stay firmly rooted in their own perspectives? This turned out to be what ties the siblings together and why Beth is the primary character. While she complains about a lack of respect as the youngest in the family, she is who every family member counts on throughout the story, in various ways, to bring herself and the family to where it wants and needs to be. This makes her evolution or coming of age at the end that much more valuable.

Loons, eagles, bears, rock bass, and many other wild creatures are a constant presence in the book, in addition to your rich descriptions of island plant life, the moodiness of Lake Wigwakobi, and constellations in the northern night sky. It’s obvious, you gave Mother Nature a prominent role in The Best Part of Us. Can you tell our readers why you wrote the story this way?

I wanted to write a novel where nature is as much of a character as the people to inspire readers to remember and reconnect with places that they care about, whether it’s a national park, a family cottage, or even a backyard garden, because we are all a part of and interconnected with the natural world every day, even if we don’t recognize it. By focusing more of the novel’s details on the lake, island, and wildness, readers are immersed in nature’s beauty, breath, and variable personalities, from its calming underlying presence to its power and moodiness, as you suggest. I also wanted to write a hopeful story that reflects nature’s constancy, that we could still return to a beloved place in the natural world and find it almost the same as it was fourteen years ago, as Beth did. Readers thus far have loved seeing nature as a character and it has reminded them of favorite places they’ve visited recently, and as a child. Many have also mentioned that they’ve considered how valuable nature is to them now, after reading the novel and in the midst of the COVID pandemic, even if it’s just a walk around their neighborhood.

Selfishly, escaping to Beth’s island and lake was great fun!

Numerous Welsh phrases, customs, and celebrations punctuate life on Lake Wigwakobi thanks to Taid and Naina, Beth’s grandparents. The strong connection the elderly couple feel toward their homeland mirrors those felt by the Ojibwe characters to their ancestors and the region. Please talk about your decision to contrast the two cultures?

As I mentioned earlier, I wanted to include the Ojibwe to reflect the reality that they live in that part of Ontario and throughout the Great Lakes region, and because they represent a cultural and spiritual philosophy deeply connected with nature. Taid and Naina represent the more patrician or Anglo-Saxon viewpoint: they love the lake and island for their similarities to Wales and to enjoy being there with their family, but Taid builds his cabin and trails to the top of Llyndee’s Peak as a way to own versus revere the land. They don’t spend much time in nature, for example, as do Beth, Dylan, and Ben. Even with this different perspective, they have a deep emotional connection to the island because of their own family memories, traditions, and celebrations while they’re there. So each side of the conflict has justifiable reasons for believing the island should belong to them. This contrast also provided the opportunity to consider the more basic question: can anyone can really own a piece of nature?

Lastly, are you currently working on another project and can you tip your hand about what we might expect?

I’m working on a piece that reflects the positives and negatives of our current COVID life—especially our dependence on our health care workers, expecting them to be superheroes in spite of some people’s unwillingness to protect their own health—and the impact of one nurse’s random act of kindness that could change her and her family’s life in ways she can’t imagine. Nature again plays a strong role as she tries to fit the clues together of who she was so kind to and how, amongst all of her heroic acts over the course of the COVID pandemic, that she will inherit his or her entire estate of 500 million dollars—if she can answer the clues correctly and remember that person within the next four months. I understand now why authors love to write mysteries!

Barbara Hodge