Award-winning memoir of madness, resilience, and hope

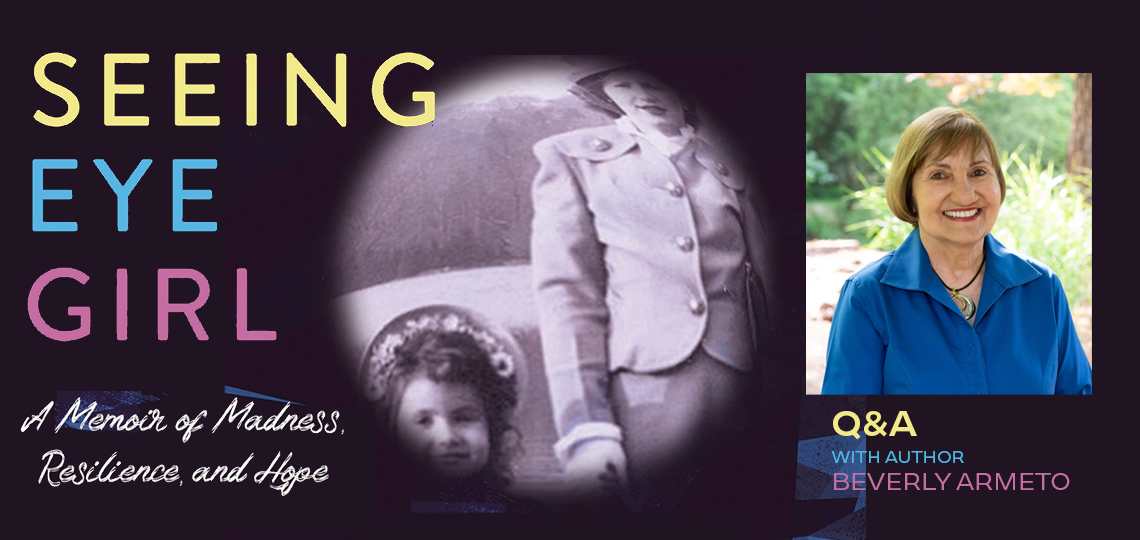

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Beverly Armento, Author of Seeing Eye Girl: A Memoir of Madness, Resilience, and Hope

Every so often a memoir comes along that takes our breath away as it depicts a life beyond imagining. Such books are a reminder to never look away. That we must be vigilant in our efforts to protect the young and the innocent—too often, silenced young children who society brushes off to the fringes.

In Beverly Armento’s Seeing Eye Girl, we hear firsthand of her twenty-plus years with a sadistic mother—and how she finally mustered the self-worth to escape.

Tellingly, Beverly uses the word “captivity,” as in she was psychologically imprisoned by her mother’s dominance. That her mother was blind and relied on Beverly for most of those years further explains Beverly’s torment.

To learn more about this remarkable woman and the message of strength she has to share, we assigned Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland to read Seeing Eye Girl and then connect with Beverly for the following interview. He readily admits that the book changed him forever.

In order to explain your book’s title, and your “seeing eye” role, let’s pull a quote from chapter one: “For the first nine years of my life, Momma was blind. But then her sight was restored. Now, only six years after her two successful corneal transplants, Momma’s eye disease has reinfected both corneas. A deep sadness fills me. Momma’s going blind again.” If it’s possible to briefly overlook everything else about your relationship with your mother, can you give us a sense of what it’s like to be someone else’s eyes? And then, at that “momma’s going blind again” moment, can you talk about the dread you must have felt when you realized you would be forced back into seeing for her?

Even as a young child, I realized Momma couldn’t see, and I intuitively made sure all my toys and clothes were stored neatly out of the way after I’d used them. I also knew that nothing breakable should be left out on the tables or counter tops. I don’t recall anyone “teaching” me these things, although that may have happened. As young as seven, I was leading Momma around our neighborhood, orchestrating bus trips to the grocery store, and reading labels, mail, and the newspaper aloud to her. At home, I was in charge of organizing the food storage in a logical way and making sure everything was in its place so Momma could easily find what she needed. Even after Momma’s first corneal transplants in 1950, I continued doing much of the work around the house, keeping things in order, and tending my younger siblings. I actually loved being helpful, and never saw these “tasks” as work.

When I realized Momma was losing her sight again, I really never felt dread for myself. Rather, I was deeply sad that she would again be blind. Her eye disease had re-infected her corneas and eventually she was able to have a second set of corneal transplants. Of course, I hoped this second surgery would give her a breath of fresh air, but that wasn’t to be.

In the mid 1950’s, after years of promise and national attention, your mother gave up on her art career, which proved to be a turning point for the family, and also led you to the realization that you didn’t want to become your mother. Why was this such a profound moment?

By the time Momma’s loss of vision was evident, six years after her successful corneal transplants, she was in a bad space all around. Serious delusional thinking was prompting her to behave in bizarre ways, her eyesight was fast failing, and she was receiving no support and encouragement for her art lessons. In retrospect, it is obvious to me that she had to be seriously depressed. When we moved to Garfield in 1956, she failed to erect her art table and easel and never again drew. She turned to men, and the steady stream of company into the house in the wee hours of night, affected all of us kids. It was when she and the men brought me into a dangerous situation—toward behavior that was frightening to me—that I knew I didn’t want to be like her. Certainly, I had that thought long before then, but Momma’s overly-promiscuous behavior made this realization crystal clear to me.

Through all the years of abuse and violence inflicted on you by your mother, you maintained a relationship with God. Can you talk about the dynamics of that relationship; why and how did you keep faith?

As an infant, I was baptized in the Catholic Church, as per my father’s wishes. When I was seven, though, I started going to a Baptist church, as it was close to Victory Homes, and I immediately got caught up in the religious zeal of the place. Like school, church became my safe place, and I was “all in” on the activities, the people, the ideas. In my child-like thinking, I soon began to “count on” Jesus and God to be with me at home and to protect me. Actually, it seems I was always talking with Jesus, praying for help dealing with the chaos of my home, making bargains—if you save me from this bar of soap, I’ll become a missionary!

By the time I was in high school and then college, the Methodist Church had become my home, my religious beliefs had matured, and I was a firm “believer” in basic Christian principles. Most importantly, I knew there was a God whose presence was always with me and we were in continuous conversations. Pragmatically, I think that belief supported Strong Beverly, enabling her to keep going and have hope for the future. Belief in God also strengthened Weak Beverly, providing comfort when there was none. I eventually lost faith in the institution of the church but remained a strong believer in God.

As a high school junior, fresh off earning an invite to join the National Honor Society, both your guidance counselor and English teacher, Mr. Tengi, strongly encouraged you to get a college degree and become a teacher. Your mother, unsurprisingly, was resistant to the idea. With such a tumultuous upbringing, how did your academic achievements and dreams of career—as a young woman in the 1950s, mind you—influence your sense of self?

How great was it for me that I loved school, loved to learn, loved new challenges, and tended to do very well in these efforts? And how good that my teachers encouraged and literally empowered me, a poor kid from the projects, and yes, in the 1950s!

The high school counselor had distinctive ideas about who girls should be: secretaries, nurses, and teachers while the boys were encouraged to become engineers, attorneys, and businessmen. At the time, we didn’t realize the limitations of the boxes we were “assigned” but, for me, becoming a teacher “fit.” I loved my teachers, had wonderful role models, and felt a “missionary” zeal to pass on the messages they’d transmitted to me: you can do just about anything you put your mind to. Work hard and focus on your goals.

My face to the world at school was that of Strong Beverly, confident, capable, happy. My academic achievement defined me and I was proud of that. It was what eventually opened doors to scholarships and then college. As I worked to become a great teacher like my own, my entire concept of myself became wrapped in that cloak.

There’s a moment during your student teaching when you reflect on all the teachers (including Mr. Tengi) who made a difference in your life. Please talk about the importance of those people, their classrooms, and education, in general, to you.

I cannot over emphasize how important school, learning, and my teachers were to me—then and now. I was safe in school and my teachers—yes, all of them—somehow made learning fun. My teachers were caring, supportive, and encouraging, and I desperately needed all of that.

In retrospect, of course, there’s an interaction between what students bring to the table and how the teacher interacts with the child and the content. In any case, I became Strong Beverly once I stepped into the classroom. I was free to be myself: funny, thoughtful, happy, and self-confident! Amazing. I was a leader. I earned great grades. I wasn’t popular, but that was fine with me. If I’d been invited to a birthday party or out on a date, I wouldn’t have a thing to wear and I wouldn’t have known how to behave. But in school I knew how to perform and it served me well in the long term.

Learning and my achievement became paramount to me and eventually became part of my route to a more balanced, better life for myself. Teachers served as my surrogate parents, in a large way. Judy Wise, my student teaching supervisor, left indelible marks on me as she showed me what great teaching and sound learning looked like. Her modeling influenced my lifetime of teaching. Much later, I realized that the face to the world I presented in the classroom was part of my maladaptive coping mechanism for hiding the trauma in my life. Then, I knew I had to repress my emotions and in the short term that worked for me. All that mattered was doing well in school, earning the praise of teachers, and eventually committing myself to pass on the good elements to my own students and to the educators with whom I worked.

After seventeen years, your father comes back into your life—ironically, at about the same time your stepfather deserts your family suddenly. What are your late thoughts on father-daughter relationships as it relates to your life?

It may be idealistic to think, but it is my recollection that the first five years of my life were wonderful: I had loving parents and I was an adored child. When the family fell apart and my father walked away from us, I was devastated, and throughout those seventeen years of his first absence I longed for him, thinking he’d be the one to “save” me from the abuse in the home. Needless to say, when he did show up—and subsequently from then to his death in 1990—our relationship was complex and difficult.

It seems that kids naturally yearn for any missing parent, and build that person up in their minds, as I did. Perhaps, the absent parent also idealizes the lost child. If and when they do meet, it’s difficult to fill the shoes of the person in your imagination. At twenty-four, I left home and lived with Dad and his then wife. It seemed he didn’t quite know what to do with me, how to treat me. He certainly didn’t want to talk about anything that happened in his absence and never apologized or explained a thing. Silence once more. All of that was disheartening. Throughout my life I’ve sought after surrogate mother and father mentors to fill the voids.

The detail you remember of your childhood is astounding. Why do you think these memories are so indelible in your memory?

I organized my chapters around the turning points in my life. These events are important, shrouded in emotion, and stored as images in the brain. You remember such events more clearly because they are etched with lots of feelings in your mind. I spent considerable time prior to writing collecting and organizing a range of artifacts: photos, newspaper and magazine articles about the family, research I had done on questions to which I had no answers, and so on. These materials aided my memory.

When I sketched out scenes, I’d surround myself with the photos of that time, and the scene, if possible. More than likely, there were no photos of most scenes, so I’d “day dream” for a long time trying to recall just what happened—along with as many details as I could muster. As I wrote I’d recall more. Every once in awhile my sister or a cousin would come across a photo or letter and send that to me, jogging my memory about events I’d totally forgotten. For example, the manuscript was almost complete when my sister found old photos of Dr. Yerzley and our family at the Jersey shore. I’d totally forgotten that. The new photos prompted me to recall and eventually write an entirely new scene.

But I also have that year and a half (from ages five to seven) where I’ve completely lost all recall, probably because I was so traumatized after the family disintegrated. So, memory can’t always be counted on. My siblings read various iterations of the manuscript in the effort to catch errors or failings of my own memory. The final book is my best effort to recall with honesty and from my perspective the events, the emotions, and the behaviors of the characters.

You struggled with bulimia nervosa, severe depression, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder in your late teens and early twenties, including suicidal thoughts that consumed you while supporting your mother and stepbrothers early in your teaching career. As you say, “I don’t want to live the rest of my life as momma’s captive.” Please tell our readers how you finally resolved to end your captivity.

After seventeen years of chronic physical and mental abuse, I was at the end of the road. I was embedded in a toxic co-dependent relationship with my mother, was filled with guilt, and was hopeless. My attitude that I was responsible for the family kept me in the dysfunctional home while my inability to envision a healthy future drove me to make a plan to end my life.

Meanwhile Strong Beverly was still there, showing up for my first class every day, presenting myself as a happy, capable young teacher. The turmoil in my mind kept me stuck on these two choices: stay there or drive into the Passaic River. One particularly long night of beatings found me hunkering on the kitchen floor, struggling to decide on one of these two options. I wasn’t alone as the voices of my angel teachers and my fantastic class of fourth graders echoed in my mind. God was there also, as I counted on that voice to give me a sign, to guide me through yet another crisis. Eventually I realized I had a purpose for living: to teach another year, to empower my students as my teachers had done for me. I had hope. Envisioning myself in the teacher role enabled me to see that I had a third choice: I could leave. I was able then to make a plan to complete my first year of teaching and walk from my current life to create a new one. There was nothing more difficult than this.

Every mother and daughter relationship is different in its own way. What is your hope when you imagine another traumatized young woman reading about your life?

My story is really a case study, with its themes echoing through the minds of many young people who are suffering from adverse childhood experiences or young and even mature adults who harbor and continue to be affected by such trauma. For those readers whose lives resonate with mine, my hope is that through reading Seeing Eye Girl, they will be inspired to search for their purpose, their sense of hope for their future. I would hope they would confide in trusted mentors, seek professional help, and eventually find a way to create a more-healthy life for themselves.

As I speak with readers through book clubs, conferences, or other settings, I hear personal stories of trauma. Many say they have never voiced these stories before and the pain they continue to feel is overtly evident. I believe the book “gives folks permission” to reflect on their lives and talk about their own situations with honesty and openness. For that I am eternally grateful.

You’ve recently retired from a fifty-year career in education. What occupies your time? Are you working on another writing project?

I am so purposefully busy with new writing, book reviewing, and activities surrounding Seeing Eye Girl. My fall calendar is full of speaking with more book clubs and mental health organizations, participating at writing conferences, and presenting keynote addresses to large groups. My new writing project is a father-memoir—there is more to that story I feel compelled to tell. A documentary of my life is currently also in the works. There’s never a dull moment.

Of course, I spend time with my many great friends and family, playing in the dirt in the garden, and nurturing the emotional, social, and spiritual aspects of my life. I have finally become a member of a church where I am once again finding my place. I am thankful every day for good health and for the life I’ve been able to create—with lots of help from my friends, family, and mentors.

Matt Sutherland