Best Of 2023, Round One - Foreword This Week

As we do at the very beginning of every year, this week we’re offering you an assemblage of our favorite questions and responses from the previous year’s fifty-plus interviews between reviewers and authors. Please give this an attentive read—we know you’ll find a few nuggets of wisdom to help make 2024 a year of great gains and growth.

Reviewer Karen Rigby Interviews Cheuk Kwan, Author of Have You Eaten Yet?: Stories from Chinese Restaurants Around the World

Authentic or fusion, Chinese food is regional and different everywhere, but is there an essence or ethos that you feel ties it together? What makes a dish distinctly Chinese?

This is a hard question to answer. In my book, I mentioned that there are fifty-five ethnic groups in China each with its own distinctive cuisine, not to mention regional variations within the majority Han Chinese, which comprises ninety-two percent of China’s population.

But if I have to point to something, it’s the way Chinese treat their food. For them, eating is very much the essence of life and an important part of one’s well-being. There’s a whole consideration for the yin-and-yang balance of what you eat; that holistic way to look at food and health; and the communal way food is consumed. That’s why “Have you eaten yet?” became a colloquial greeting meaning “How are you?”

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Erin Sharkey, Editor of A Darker Wilderness: Black Nature Writing from Soil to Stars

The writers in this collection greatly expand the definition of nature writing. As your introduction points out, this genre has been dominated by white, male, cisgender perspectives. Are there other writers (aside from those in A Darker Wilderness) not typically associated with this genre whom you would add to the traditional nature writing pantheon?

Oh, so many writers. For me, the best poetry is sensual and evocative. Often, that means poetry that contains natural elements and nature themes because they are inherently sensory. I think of Lucille Clifton; so many of her poems use simple natural objects: the waters, wind, ribs, clay, claws, melt, vapor, lips, nose, and stone to evoke themes of loss, belonging, fatigue, pride, and love. Read any Toni Morrison novel for its nature themes. That will blow your mind. I think of Earthseed, the fledgling faith system in Octavia E. Butler’s The Parable of the Sower, which features many themes of conservation, of change, foraging for seeds, of reading nature’s signs, and reading the stars for direction.

One of the reasons Black writers have been left out of the nature writing canon is that contemporary Americans view nature as separate from us, as something we need to seek out outside of ourselves. Nature needs to be conquered. It needs to be owned and categorized, and ordered. We can not ignore the colonial history of the genre of nature writing because the exclusion of Black folks has had consequences, as has the ways other people of color’s relationship to nature has been relegated to some innate primitive connection. Think about the ways Jim Crow laws kept Black people out of swimming pools many decades ago and their ties to higher rates of drowning for Black people. Or Sundowner laws, which kept Black folks outside town limits after dark, have inevitably contributed to a lack of land ownership by Black people in rural communities. It was not that long ago that that kind of stratification was a rule of thumb for organizing bookstores as well, relegating Black authors to the Black books shelf.

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Matthew Birkhold, Author of Chasing Icebergs: How Frozen Freshwater Can Save the Planet

Are creative solutions like iceberg harvesting a key direction to pursue as the climate crisis accelerates?

We will have many urgent problems to tackle in the future. Some will involve trying to slow or reverse the devastating environmental consequences we’ve unleashed. Others will require us to act urgently to address acute human emergencies, like water scarcity. Creative solutions and outside-the-box thinking will be essential to solving any of these issues. As the climate crises accelerates, huge portions of the planet will run out of safe drinking water. Icebergs may be a great solution to this shortage—but whether harvesting icebergs saves the planet will depend on how we approach and regulate the practice.

Reviewer Erika Harlitz Kern Interviews Costanza Casati, Author of Clytemnestra

In the Greek texts, Clytemnestra is put forward as an example of how a woman should not behave, something that tends to carry over into our modern readings of her. But in your novel, you took another route and instead presented Clytemnestra as a person with a genuine backstory and deep personality. What made you decide to write a novel from Clytemnestra’s perspective? What was it you wanted to say by making that choice?

What I love the most about Clytemnestra is that she is a woman who sees herself as equal to the men around her and who would do anything to protect the ones she loves. For me, she is a good person, and I believe it was important to write her thinking she was a good person at heart, even when she did bad things, otherwise the novel wouldn’t have worked.

As you say, modern readings of Clytemnestra tend to depict her in a negative light, as the archetypally bad wife: a lustful murderess who doesn’t know her place. While I was writing my novel, I was really interested in the contrast between how she perceives herself and how others perceive her. There’s a quote towards the end of the book that says, “Heracles, Perseus, Jason, Theseus … songs about them are sung, and their cruel deeds are turned into sunlight. As for queens, they are either hated or forgotten. She already knowns which option suits her better. Let her be hated forever.”

Throughout the novel, Clytemnestra is aware that her deeds aren’t considered heroic, because she is a woman, but she doesn’t care. This is something that comes across even in the ancient texts. Two of my favourite quotes are from the Odyssey and Agamemnon. The first is by Agamemnon, the second by Clytemnestra, and both talk about her murder of her husband. “There’s nothing more deadly,’“he says, “bestial than a woman/ set on works like these––what a monstrous thing/ she plotted, slaughtered her own lawful husband!,” while she says: “I brooded on this trial, this ancient blood feud/ year by year. At last my hour came. / Here I stand and here I struck/ and here my work is done.” He thinks her bestial, she thinks herself heroic.

Reviewer Carolina Ciucci Interviews Maria Rodale, Author of Love, Nature, Magic: Shamanic Journeys into the Heart of My Garden

Combining gardening and shamanic journeying makes it clear that the two have more in common than one might think. What would you say are lessons to be learned from both?

Pay attention. Listen. Nature is trying to communicate with us! Nature is love made visible. And good, true love is a relationship where everything and everyone feels seen, heard, and cared for. There are many gardens that are visually perfect, but not loved. Real love allows for some freedom and wildness.

“Perfect” gardens are like “perfect” families on social media. Visually they seem perfect and we can feel inadequate compared to them, but underneath there is often pain, trauma, and loneliness. Embrace your wildness and imperfections and you will discover more joy and more love.

Reviewer Jeremiah Rood Interviews Oren Kessler, Author of Palestine 1936: The Great Revolt and the Roots of the Middle East Conflict

I really enjoyed reading the book, in part because I had this ever-present sense of hopefulness that things would work out. Let me back up a bit. The book covers the Great Revolt of 1936-39, a relatively small time frame and scale violence that becomes the “crucible in which Palestinian identity coalesced.” It pits nationalistic Arabs against Zionist-minded Jews in a struggle over both land and power, a conflict that echoes all these years later. What do you hope people better understood about the history of the conflict?

I hope this book can illuminate a forgotten but hugely formative chapter in Israeli and Palestinian history, and of the Middle East conflict itself. I argue that many facets of that conflict’s “template” took shape not in 1967, when Israel took control of the West Bank and Gaza, nor even in 1948, when the Jewish state was born, but a decade before. It was then that Palestine’s Arabs first united in concerted action against a common foe: Zionism and its midwife the British Empire. It was then that Palestine’s Jewish community became a force to be reckoned with militarily, economically, and demographically. And it was then that momentous concepts like “Jewish state” and “two-state solution” first appeared on the diplomatic agenda.

I won’t be so bold as to claim that learning about this period will magically solve the Middle East dispute, but I do argue that it fills some crucial historical gaps in understanding how we’ve reached this point of apparently endless discord and hopelessness.

Reviewer Jeana Jorgensen Interviews Thomas Cirotteau, Coauthor of Lady Sapiens: Breaking Stereotypes about Prehistoric Women

The entire book warns against applying modern Western gender norms to ancient peoples. This is especially evident in the stereotype about “man as hunter, woman as gatherer.” Why do you think these stereotypes remain so prevalent?

It seems to me that our Western society in which we live still has a lot of progress to make in order to give women their rightful place in many areas. We are the product of our past, and it has put men in the limelight most of the time while forgetting about women. But fortunately, this society can and must change. If you allow me a personal anecdote, I have the great fortune to have two daughters who are teenagers. They often complain about the sexist remarks they receive or hear in their school lives. There is a considerable challenge to make the younger generations, boys but also girls, understand that being a woman does not force you to accept all these stereotypes.

Reviewer Ashley Holstrom Interviews Ruby Warrington, Author of Women Without Kids: The Revolutionary Rise of an Unsung Sisterhood

In the end, it all comes down to bodily autonomy and the patriarchy. How do you hope the world changes in favor of women?

I wouldn’t say it all comes down to this—economic and environmental concerns are two of the biggest drivers behind the drop off in the birth rate. But yes, this is equally the result of more women having more say over what we do with our bodies and how we live our lives.

However, a “patriarchy” by definition privileges and exalts maleness and masculinity. The fact that more women are rejecting motherhood—which in many ways is the ultimate feminine gender role—or are feeling frustrated and subjugated in their mothering, shows the extent to which patriarchal values govern all of our lives. Simply put, under patriarchy it pays for women to be more “like men,” and becoming a mother is antithetical to this.

For the world to change in favor of women—or in favor of “the feminine”—we will need to revalue femaleness and femininity, beginning perhaps with revaluing the unpaid labor of childrearing.

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Matthew Vollmer, Author of All of Us Together in the End

Your work embraces hybrid forms. How does crossing genres help you to tell the stories that need to be told?

We think with words. And what are words but expressions of thought? With thoughts, therefore, we make the world. And how myriad are the forms that the world makes! And then: how do I speak about the things I see and feel? The apprehension of a tree may suggest discursiveness, a many-branched digression, or it might suggest shade and shadow and obfuscation. The rootedness of the tree might imply groundedness, or its wind-stripped leaves a delightful fragmentation. Depending on the day and hour, or the weather, or the season, or my mood or disposition, I will certainly require different words in my attempt to cast my perception of the tree in the amber of language—and I will also need different forms.

The representation of lived experience, then, will always necessitate a particular shape. Sometimes this representation is rather straightforward; on other, more complicated occasions, a melange of sorts is in order.

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Henry Hale, Co-author of The Zelensky Effect

Do you envision a Ukrainian victory and what might it look like? What do most Ukrainians want for their country’s future?

I do think Ukraine is likely ultimately to win, though exactly when or how is hard to say. I see two primary scenarios. One is a very long and grinding war; prior to 2022, for example, the war had already raged on in the Donbas for nearly eight years, resulting in well over 10,000 deaths. Ukrainians have resolve and Western military arms on their side, but Russia has the sheer force of numbers now that President Vladimir Putin has taken to mobilizing hundreds of thousands of young Russians to throw into the meat grinder for his expansionist plans. The other scenario, though, is that Russian military failure and Ukrainian gains could, at some point, trigger an unraveling of the Putin regime. This is one reason why this spring and summer are so important: If Ukraine’s planned counteroffensive achieves major successes, the “unraveling” scenario in Russia becomes much more likely, though it may take some time to play out.

For peace, most Ukrainians are not willing to accept anything less than full restoration of their boundaries as internationally recognized (including by Russia) upon gaining independence in 1991, and they also seek reparations from Russia and prosecution of those responsible for Russia’s war crimes. Bigger-picture, though, Ukrainians see their country’s future as prosperous and European. While largely symbolic at this point, the EU’s granting of Ukraine candidate membership status last year was very important to many in Ukraine as a sign of hope for the future and a commitment on the part of its government to undertake needed reforms. Hope is thus very high now in Ukraine that it will truly one day become a “normal” European country.

Reviewer Erika Harlitz-Kern Interviews Artem Mozgovoy, Author of Spring In Siberia

The focus of the story is on the persecution of gay people in Russia. Why is it important for people to know what is happening, and what do you think that people outside of Russia can do to support gay rights in Russia?

When I hear my American friends say that “there’s no worst place to be for a queer person today than Florida,” I have to take a deep breath … Why is it important to be aware of what’s happening in Russia? In Ukraine? In Iran? In Kenya? In Uganda? To me the answer is so simple … The world would be a place far less lonely if we learnt to hear one another. We would understand ourselves much better and, perhaps, even find ways to better our own future.

Listening, hearing, learning to relate to the seemingly most distant points of view and voices is also the best support one can give, the best support one can receive. We’re one. We’re in the same boat—yet we keep ignoring it.

The war in Ukraine and its potential escalation into the Third World War is the clearest signal of our inability to establish contact, to hear each other. In the same way COVID-19 served us the best (or the worst) of signals of the humanity’s exorbitant abuse of nature. At some moment, we receive punishment for our arrogant ignorance.

Reviewer Kristen Rabe Interview Chris Impey, Author of Worlds Without End: Exoplanets, Habitability, and the Future of Humanity

Your book also examines moons—those in our own solar system as well as those orbiting exoplanets. What are we learning about planetary moons, and how likely is it that they could support life?

Moons in the outer parts of our solar system sometimes have all the ingredients for life: carbon-rich material, liquid water, and a local energy source. Perhaps a dozen moons have potentially habitable locations, including moons of Uranus and Neptune, though we still have much to learn about them. The best candidates for life are Jupiter’s Europa, Saturn’s tiny Enceladus, and Saturn’s large moon Titan (for a weird version of biology). If what we’re seeing in our solar system is typical, we should expect that there are habitable exomoons (or moons orbiting exoplanets). They are extremely difficult to detect, however, so this is research for the future.

You include a fascinating history of philosophers and writers who have pondered the nature of the universe, from ancient Romans to Isaac Asimov and James Cameron. Talk about the intersection of science and the imagination. How does art help us think more expansively about our planet and what’s beyond?

Astrobiology is the perfect subject for creative speculation since we know only one example of biology. The universe has probably conducted some wild and bizarre experiments given all the habitable real estate and vast spans of time. For example, an Earth clone could have formed eight billion years before the Earth did, and so it would have had that much head start for evolving creatures. Weird biology is on the table, as well as forms of life we might not even recognize. Art helps us imagine and visualize what might be possible as opposed to what is.

Reviewer Catherine Reed-Thureson Interviews Celeste Larsen, Author of Heal the Witch Wound: Reclaim Your Magic and Step into Your Power

The book discusses how the witch wound affects people today. Can you explain why it is so important to address and heal this wound?

The short answer? Because this is your life, and you deserve to live it as your truest self, doing and experiencing all the things that make you happy without fear or shame. Period.

The longer answer is that the witch wound is insidious, and can affect us in all kinds of seemingly unrelated ways. Deeply rooted limited beliefs (such as the idea that your intuition cannot be trusted, that your emotions are “too much,” or that you are not creative enough) can cause you to delay your dreams and limit your own potential in order to meet societal expectations. Fear of rejection can lead to stifling your self-expression, dimming your own light, people-pleasing, and allowing personal boundary violations. The witch wound can also show up as feelings of shame related to sexuality and the physical body, especially for women.

In my own life, the journey of healing my witch wound has opened so many doors—many of which I never even realized were locked.

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Jeff Biggers, Author of In Sardinia: An Unexpected Journey in Italy

If you had to describe the spirit of Sardinia and its people in just a few words, what would you say?

“If there is a word to express the feelings of the Sardinians in the millennia,” of ancient times, the great Sardinian writer Sergio Atzeni wrote, “perhaps it is happiness.” Despite invasions over thousands of years, from the Phoenicians to Carthaginians to Ancient Romans to the Goths, Vandals, Spaniards (until Italy’s unification), and contemporary crises over economic development, Sardinia has carved out its own unique ways, cultures, languages, and stories—and altered European history in the process. Such happiness, as a form of resistance, is evident in the exuberance we see in so many of Sardinia’s enduring festivals, processions, and its strong traditions of music, song, and dance. And I’d add beauty, in both the stunning landscape and its colors, from the sea to the Supramonte mountain ranges, and in the people and their cultural ways; Sardinia is rightfully called the “pearl” of the Mediterranean. But there is also another Sardinia—the Sardinia in the forefront of the arts, literature, music, architecture, cultural innovations, political leaders, and more.

Reviewer Dontaná McPherson-Joseph Interviews Dorothy Lazard, Author of What You Don’t Know Will Make a Whole New World

As I was trying to craft a final question for you on the myriad ways you realized, explored, and fully rooted yourself in your Blackness, particularly during the time now known as the Black Arts Movement, and after, I’m finding it difficult to word. I felt a pang in my soul when you talked about realizing how you would need a public self and private self as a Black child in a white space. I felt your excitement, your confidence, and your sense of belonging grow through middle school and high school.

Perhaps what I’m most curious about is this: Do you feel more rooted in your identity as a Black woman today than you did back then? If so, in what ways and what contributed to that? What words of wisdom do you have for other Black girls and women today?

It’s not that I needed a public self and a private self, that’s just the way society was set up—with the Black community, my Black family influencing me in one way and the white, “mainstream” society expecting me to act in another way. Did I “need” that dichotomy? No. But how can we expect any other result when we have a society that is split along racial lines, where whiteness is paramount, and blackness is demonized?

I feel rooted in my Black identity because of the Black Arts Movement which taught me and my peers that we were beautiful, whole within ourselves, that we were not all the negative labels that society had assigned us. During that time, we had to learn to see ourselves, love ourselves as we were, not as white society said we were. That was liberating to hear and see. There was a lot to unlearn. I see my youth, the period I depict in my book, as a time to retire my sense of self. Too often Black children learn self-hatred before we consciously learn self-love. And that’s a pity.

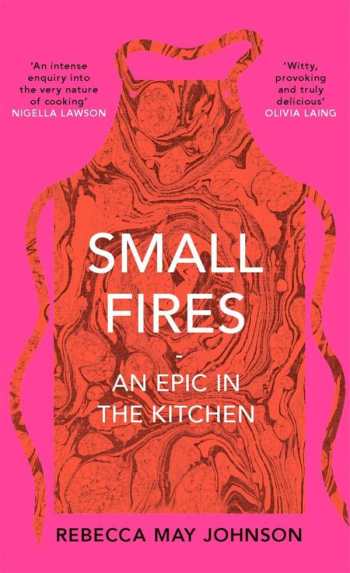

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews Rebecca May Johnson, Author of Small Fires: An Epic in the Kitchen

Your aim of learning to think and cook critically as a way of resisting the patriarchal history of knowledge really comes through in this book. You consider this all through the lens of your “hot red epic,” the tomato sauce recipe developed over ten years, ten kitchens, and thousands of iterations. What drew you to this recipe as your focus?

Every time I tried to think about what I knew about cooking and to identify the moment when I developed a meaningful understanding of it, I came back to this recipe. Occasionally in life, I gain a transformative insight that changes how I see the world and how I live—often this has been through study or reading, and from talking to people. This recipe brought about such a transformative moment, too: the first time cooking the recipe was a wild, paradigm-shifting experience—revelatory and ecstatic!

I suddenly perceived ingredients and the processes of cooking as never before. The recipe gave me principles for understanding so much beyond that one dish and became a kind of grammar that enabled me to speak through cooking—to express myself, and to communicate. As I began to document all the times I had cooked the sauce, I realised how much of my life was contained in the recipe, how many relationships of all kinds had come into being while making it.

Matt Sutherland