Book of the Day Roundup: November 11-15, 2024

We Called Them Giants

Kieron Gillen

Stephanie Hans

Clayton Cowles

Image Comics

Hardcover (104pp)

978-1-5343-8707-2

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

A teenage girl encounters huge, mysterious aliens in the engrossing graphic novel We Called Them Giants.

Lori, who is used to being moved between foster families, feels hardened to the world. When she wakes to find that most of the population has disappeared, she reasons that “The rapture is when all the good people disappear. I don’t believe in good people,” so this can’t be that. She and schoolmate Annette team up to navigate their strange new circumstances. On the run from a gang, they witness a pair of giant aliens fall from the sky. Annette is taken by the red giant; later, it saves Lori’s life. Suspicious of the red giant and unable to understand its language or motivations, Lori comes to realize that, despite her initial doubts, the giant is her best hope for survival.

The story is fueled by bold narrative decisions. The mass disappearance of humans and arrival of the aliens are kept mysterious, creating tension and intrigue as people gather information through guesswork and experience. Lori’s emotional breakthroughs and rediscoveries of how to trust are a satisfying second thread. And the illustrations are sleek and dynamic, with invigorating depictions of movement throughout. Their expert showcase of colors emphasizes the contrasts between the bleak, barren environment and the potent, powerful “otherness” of the aliens.

We Called Them Giants is a thrilling graphic novel about alien contact on a postapocalyptic Earth.

PETER DABBENE (October 14, 2024)

Something Close to Nothing

Tom Pyun

Amble Press

Softcover $19.95 (260pp)

978-1-61294-299-5

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

In Tom Pyun’s biting novel Something Close to Nothing, two exes learn to accept the imperfect but wonderful world as it is.

Wynn and Jared seemed to have it all: a nice house, a successful long-term relationship, and, thanks to a Cambodian surrogate, a baby on the way. But at the last minute, Wynn bails to fulfill his lifelong dream of being a professional dancer, leaving shocked Jared to face parenthood alone. Navigating grief, anger, and regret, each of the men comes to an important realization about his life.

Moving between Jared and Wynn and the continents that separate them, the wry yet candid prose unearths the factors that combined to destroy their once-passionate love. Their class and racial differences are widened by a mutual sense of entitlement and a lack of self-awareness, preventing either from understanding the other or attempting honest communication. Illuminating flashbacks—some touching, some horrifying—reveal their differing personalities and the depths of their dysfunction as people and partners. Sometimes unlikable but always fascinating, they never cease to grow and reveal more about themselves.

In the months following their dramatic break-up, Wynn and Jared learn painful but necessary lessons about living mature, meaningful lives. Through fleeting, ill-fated romances and public errors both amusing and catastrophic, they come to see their relationship in a new light and accept that aspirations, as fortifying as they can be, are not reality. With this relatable, universal truth at last in hand, they try to live by the implications: that the realities they tried so hard to ignore are all they can depend on.

Something Close to Nothing is a poignant novel in which two expectant fathers learn that letting go of their former dreams doesn’t have to be a tragedy.

EILEEN GONZALEZ (October 14, 2024)

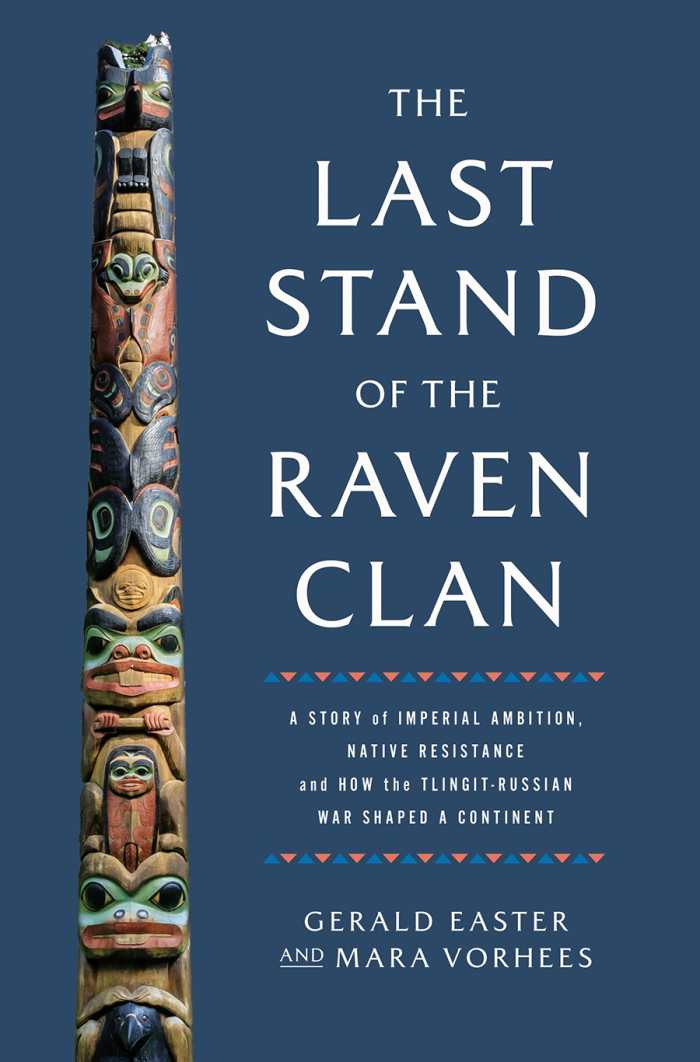

The Last Stand of the Raven Clan

A Story of Imperial Ambition, Native Resistance and How the Tlingit-Russian War Shaped a Continent

Gerald Easter

Mara Vorhees

Pegasus Books

Hardcover $29.95 (320pp)

978-1-63936-736-8

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Gerald Easter and Mara Vorhees’s The Last Stand of the Raven Clan is an engrossing history of the Tlingit-Russian war, its causes, and its impacts on North America.

Written from the perspective of the Tlingit, this refreshing narrative explores a war long ignored in white settler history. The Tlingit are introduced in the present day as proud, reflective, and perhaps a little foolhardy. This stature echoes back in time, with the book covering cultural practices of the Tlingit precolonization and showcasing their unbroken cultural spirit. The Russians are then introduced on the Great Northern Expedition. Their exploitation of the otter, mixed with their desire to participate in Europe’s colonial expansionism in the Americas, drove them to explore, expand, and conquer. Next came the Tlingit resistance.

The prose is gripping, propelled along by lyrical flourishes even through information-dense and violent sections:

A second hunter, Afanasy Liskenkov, scrambled past Baranov, but was struck by a spear and fell backward. A chorus of jeers rang down.

The beauty of the prose is supported by accounts from native people who witnessed the massacres and battles, giving a complete and rare look into how these events were seen at the time:

I was a boy of nine or ten, when the first Russian ship, a two-master, arrived. We had never seen a ship before, we did not know white men.

As a tribe without gunpowder and other modern European weaponry, their successes against the Russians are an astounding tribute to their skill as warriors and their unbroken will. Theirs is a triumphant historical account of a success forged in the face of tremendous odds.

Captivating and poetic, The Last Stand of the Raven Clan is a resonant history of Indigenous resistance whose lessons are far-reaching.

AHLIAH BRATZLER (October 14, 2024)

Mishka

Edward van de Vendel

Anoush Elman

Annet Schaap, illustrator

Nancy Forest-Flier, translator

Levine Querido

Hardcover $15.99 (160pp)

978-1-64614-458-7

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

A white dwarf rabbit brings a refugee family together in Edward van de Vendel and Anoush Elman’s novel Mishka.

Roya and her family are refugees from Afghanistan. When they learn that they have been permitted to stay in the Netherlands, they are elated. To celebrate, they bring home a white dwarf rabbit as a pet. Every day, they feed, play, and bond with Mishka. Trouble arises when Mishka goes missing on the day when Roya is to give a presentation on dwarf rabbits at school.

Central to the novel are animal-human affinities. The family bonds of Roya’s household tighten as they speak to Mishka about their memories. They have him nearby as they process their emotions from their time fleeing Afghanistan. Roya, who was too young to remember much of the journey, is inducted into this oral family history as her brothers and parents recount funny and happy moments (broom soldiers sweeping away their steps; a fellow refugee’s beautiful singing) alongside sad and harrowing ones, like being forced to burn photographs of their escape.

On occasion, Roya’s narration is awkward. Her first meeting with Mishka is described as a telepathic exchange, for example: “He looked as if he was thinking, ‘Hey.’ And that’s just what I was thinking: ‘Hey.’ But right after that I thought, ‘YESSS,’ because the dwarf rabbit was also thinking, ‘YESSS.’ I saw it and I heard it in my head.” Nonetheless, she is an earnest narrator who’s steadfast in her love for Mishka and who is persistent and determined about recovering him when he disappears. And the accompanying illustrations, done on brown paper in oil pastel, are impressionistic and whimsical.

In this moving novel about home and belonging, a beloved bunny helps a refugee family tap into their collective stories.

ISABELLA ZHOU (October 14, 2024)

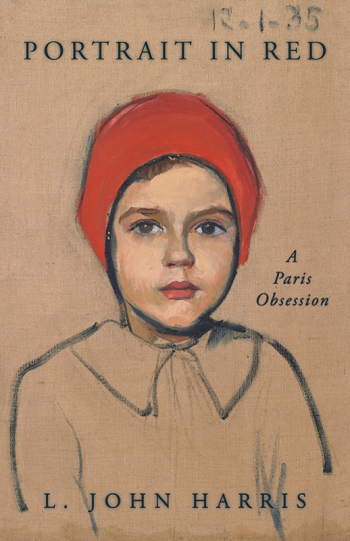

Portrait in Red

A Paris Obsession

L. John Harris

Heyday

Hardcover $35.00 (320pp)

978-1-59714-649-4

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

In his memoir Portrait in Red, L. John Harris pursues multiple avenues (and delightful detours) in an attempt to solve an art mystery in Paris.

Harris, who attended art school at Berkeley in the 1960s, arrived in Paris on magazine assignment, having been asked to assess the croque-monsieur. On his first day there, he stumbled upon a discarded painting of a girl with a red head covering. Recognizing the artist’s skill, he took the portrait home. This painting, dated January 12, 1935, but not signed, presented several mysteries: about the girl, about the artist, and regarding whether the painting was even finished.

This account of Harris’s search is digressive by design—both a record of his quest to satisfy his curiosity and a detailed account of his fixation on the painting. Humorous sketches of Harris’s long-past art school “happenings” complement his quest, as do his ranging discussions of art, food, and literature, with the text making nimble shifts from topics like apple strudel to Gustav Klimt paintings.

After his initial queries failed to unlock the painting’s provenance, Harris began staging events which were themselves a kind of performance art. He hosted an unveiling at his home in California—a formal “first viewing” suitable for a masterpiece. He created and disseminated “wanted” posters across Paris. Even the writing of this book became a part of the “happening.” Forays into numerology and references to Wikipedia, Facebook posts, and Pliny the Elder enliven the book further.

With photographs to illustrate its search, the memoir Portrait in Red is about how a stranger’s trash became an inquisitive writer’s treasure—a free-wheeling, fascinating dissertation on a found object with infinite worth.

SUZANNE KAMATA (October 14, 2024)

Kathy Young