Bracingly forthright memoir of friendship across racial and class divides

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Wendy Sanford, Author of These Walls Between Us

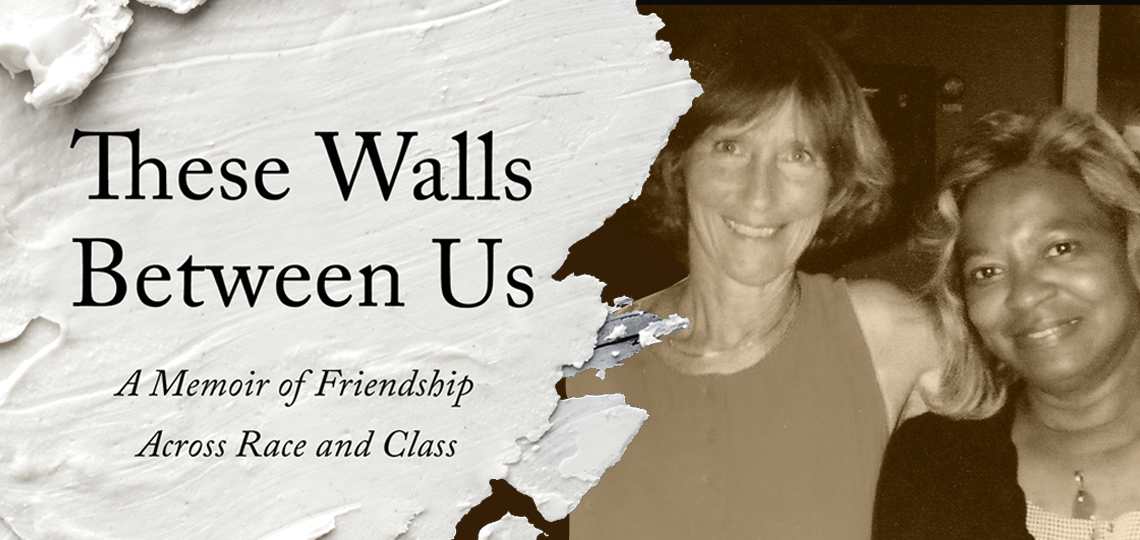

Wendy Sanford, who is white, and Mary Norman, who is Black, have created a friendship that spans sixty-five years. The story of their friendship—recounted tenderly by Wendy in These Walls Between Us—began when fifteen-year-old Mary joined Wendy’s family at their Nantucket vacation home as a domestic worker. Later, after Mary moved into a career in corrections and Wendy helped to write the women’s health classic Our Bodies Ourselves, the two turned to each other as friends. Wendy has made it one of her life’s missions to better understand white supremacy culture so as “to see Mary more fully and to become a more dependable friend.”

Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland caught up with Wendy to discuss These Walls Between Us and one of the most unlikely, inspiring friendships imaginable.

Back in the 1950s, when your well-to-do family was vacationing on Nantucket, a fifteen year old Black girl from rural Virginia named Mary White (later Mary Norman) joined your vacation household as a live-in domestic worker. You have remained good friends with Mary for more than sixty years. As you write in the introduction, These Walls Between Us “focuses on my often-stumbling journey towards seeing Mary more fully across the socially constructed barriers between us—that is, towards being a truer friend. It is written with a white readership in mind, to invite white readers to join me in exploring our relationship to white supremacy culture.” That invitation points to what may be the most important issue of our times, the one that is causing such a bitter divide in this country. Can you talk about your hopes for the book in light of the issues of the day?

Mary Norman and I have talked about this a lot: What are our hopes for the book we have co-created—I as the writer, both of us as truth-tellers? Why expose our lives to scrutiny by people we do not know? I guess our bottom-line conviction is this: If more white people can show up informed and ready for interracial friendship and cooperation, we have a chance of building a better country. Mary and I grew up divided by racial and class inequities that impact our lives in every way. If we could write a book about creating friendship across those barriers, and if I could be utterly honest about my learned ignorance, missteps and microaggressions, we felt that perhaps we could make a difference.

As we were finishing up the book, the inhabitant of the White House was fomenting white racism for his own benefit, and his supporters harked back nostalgically to the “great” America before the Civil Rights Movement. Mary said, “This book will show people what the ‘good old days’ were really like.” Today, conservative governors, state legislatures and school boards are making it illegal for teachers to give a full and accurate picture of US history. We offer our story as part of the necessary truth-telling.

White readers tell us that These Walls Between Us invites them to reflect on their own racial ignorance and gives them resources for learning and change. They express gratitude for the transparency and lack of self-blame with which I face the ways I, as a white woman, have benefited from racism and white supremacy culture. Several Black interviewers have welcomed the fuller picture of the realities and hidden rules of domestic service—including the treatment of Black immigrant home health aides in white families today. As people in communities across the country work to end the ignorance and fear behind police shootings of unarmed Black people, and organize to protect the right to vote, we hope that the hard-won friendship and love expressed in our book will be a resource for change.

As a teen, you attended an elite Maryland boarding school for girls, one with a curriculum that was decidedly light on a factual rendering of history, especially as it detailed the region’s slave history and other unflattering portraits of America. And you now call this schooling a training ground for white privilege, along with the upper-class guidance you received from your mother. At some point over the next few years, you started to see that these coming-of-age experiences were “inextricably implicated in the story of racism and white supremacy in my life.” Can you talk about the eye-opening period of your life that set you on a path to “become a citizen of the multicultural world that is our life in this country.”

You are so right that the 1970s changed my life! I entered my twenties firmly ensconced in the privileges and perspectives of my white, affluent, Republican background. By my mid-thirties, I was a feminist, a Quaker, a lesbian—and an anti-imperialist Democrat. Even my feminism was open to evolution. For a short while, white women in the budding women’s health movement thought we were naming issues for all women. Very soon, Black, Latina, and Indigenous women’s health activists challenged us not to focus mainly on issues that affected us as white women. What about sterilization abuse, they asked us. What about the critically higher maternal mortality rates for Black women? And what about the lack of government supports for new mothers living in poverty? In these exchanges, I became aware of a wider “we” that I needed to learn about and to honor. At the same time, poets and feminist icons Audre Lorde and Adrienne Rich began a public dialogue about the impact of racism on relations between women. It was a time of great learning and reckoning for me.

You and Mary set out thirty years ago to write a book together. Can you tell me how that worked out, and why you are listed as the sole author? When you speak of Mary as a ‘co-creator’ of the book, what do you mean?“

For many years after Mary Norman first arrived, at fifteen, to do domestic work during my family’s vacation, Mary used her own vacation from full-time work back in New Jersey to return to the summer job. Although we were less than four years apart in age, Mary and I were rigidly divided by our different roles in my family—Mary as a domestic worker, I as the privileged daughter on vacation. In interviews today, Mary recounts my friendly but insistent curiosity. I’d stand at her door in the beach-side cottage, asking her endless questions—with, as she says, no concept that she might want to do something else with her time. Her job description did not include saying no to me.

One summer when we were both in our thirties, things began to change. Mary and I had both married and divorced; we were both single parents; Mary was leading the way in county corrections in New Jersey as the first woman officer in the system, and I was an emerging women’s health activist. The all-white beach enclave where my family vacationed was starkly lonely for Mary, and I felt increasingly alone in my conservative family as a feminist and maybe-lesbian. One evening we wanted to talk more openly than we could in the house with my parents, so we went down to walk the beach together. This began a tradition of night-time walks on a beach where Mary was unwelcome in daylight except in the white uniform of service. We talked about our lives, our children, our work.

After many of these walks, and increasing connection between visits, Mary said, “We should write a book together. No one will believe our friendship.” We’d been sharing books by African American writers in that great flowering of new and re-issued novels and memoirs by Black women in the late 1970’s and early 80’s. I was co-writing chapters for Our Bodies, Ourselves. Writing a book together seemed entirely possible.

Things turned out differently than we imagined in that first heady moment of deciding to write a book together. As Mary said just the other day to a social justice group we spoke with via Zoom, she worked at least three jobs at all times. She gave any discretionary time to her children. She had no time to write. As an English major in college and a person with enough resources to have leisure time, I jumped in to write “our” book.

Only gradually did I come to understand that I as a white person could not actually write “our” book. These Walls Between Us began with decades of phone calls and conversations in each other’s homes, with me asking Mary questions and taking copious notes. The resulting manuscripts were in my voice, from my perspective, through my gaze—the “white gaze,” as Toni Morrison famously observed. Mary read and commented on each draft, but I knew that, given the power differences that hung over from the origins of our relationship, she might feel hesitant to criticize my work. As I learned from Black mentors-in-print like Toni Morrison, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and the leaders of Black Lives Matter, too little of Mary’s actual voice and perspective were present in the book for it to be “ours.” I nearly gave up more than once.

Finally, the project took so long that we experienced a technological breakthrough: Mary and I both got smartphones. “Ask me anything,” Mary texted me, “and I’ll answer.” We went back through the whole book, using Mary’s exact words to flesh out her experiences and perspectives. Co-creation had entered a new phase. It was still a different book than it would have been if we had both done the writing, but it felt like it was closer, perhaps as close as we could get. *These Walls *brings to life scenes from the sixty-five-year evolution of our unlikely friendship, told from my perspective, focusing on my many missteps and microaggressions as I slowly learned to see Mary more fully and to become a more dependable friend. Woven in are stories and perspectives from a number of the books that Mary and I have shared over the years.

Suddenly this had to be our final version, because we were getting so old!

I feel blessed that Mary’s two grown sons encouraged her to give me the go-ahead to publish the book as it is now, that they find her present in its pages in so much of her accomplishment and complexity. Even though it is most honest to list me as the sole author, we honor each other as co-creators. We decided that a percentage of proceeds from These Walls will go to the work of the Equal Justice Initiative in Montgomery, Alabama. (Founder Brian Stevenson is a hero to both of us.) The rest goes to Mary.

The question of reparations to African Americans for the crippling legacy of enslavement in a country that built its wealth on their labor is rightly in the public eye these days. I think of my years of working on These Walls as a kind of reparations. In retrospect, I agree with the wise people who say that, while reparations are surely about money, they are also about relationship, even about love.

Why do you think the US struggles with addressing social class?

Oh yes, we do have social class in this country! I think the US struggles with addressing class because so many people pretend that the disparities don’t exist—especially people with the most to gain from the rigid and inequitable class system. It took me years to realize how very different Mary’s life was from mine. We laugh now about how I used to worry at her that she was a “workaholic,” when, in fact, as a working class person she had to work every possible job in order to make ends meet. My learned ignorance fostered the continuation of the class barriers that damaged my friend’s life. But there’s more. Many in the “upper” classes foment anti-Black and anti-immigrant racism to keep apart groups that might work together for change. We saw this with the 45th President and his supporters, how they use anti-Black racism to rally support among white people.

But your upbringing instilled in you a deep respect for education, language, and history—leading to your interest in women’s health and sexuality, writing, and more. In fact, you admit to a little too much scholarly fervor: “When I do not work actively to uproot much of what my family and schooling taught me, these hierarchical and elitist ways of thinking structure my personality, my aspirations, and my ideas. I emerged from my schooling with a large dose of internalized superiority and a habit of dominance.” Certainly, this passion also serves you well, especially in your awareness of it. Can you expand a bit on how you live with this powerful force inside of you?

To me, conventional education is a training in the status quo. I came out of an elite version of that education shaped and limited in ways I wasn’t yet aware of—also, as you say, quite passionate about learning itself. I first experienced popular education through consciousness-raising in early second-wave feminism, and then encountered it in seminary through the work of Paulo Freire and the teaching style of Rev. Dr. Katie Geneva Cannon. In those encounters, a different kind of learning began for me. The powerful force that came from connecting my own experiences to the larger world of love and justice is what fueled me through the thirty years of writing These Walls Between Us and makes me eager to meet with readers in person and via Zoom.

Per your carefully orchestrated upper-class training, the summer after your sophomore year at Harvard, you married a young man of your social status. While describing the grand Nantucket event, you foreshadow problems to come: “Not even a perfect summer wedding could effectively shore up our marriage against the predictable backwash of our families’ dysfunctions or the oncoming tides of feminism.” Another disturbing moment from that wedding chapter finds you recounting how you remembered Mary sitting normally in the church and at the reception, but in a conversation with her decades later she lets you know that she wasn’t allowed to attend. You call it a case of “white amnesia,” a term coined by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Your memories of that time and place seem especially painful for you to recollect. Would you mind offering readers a thought or two on what those memories represent to you now that your relationship with Mary has grown so much deeper and richer?

Thank you for asking this, Matt. First of all, I feel great chagrin that my mother and I called Mary our “friend” and did not invite her to the wedding that she worked so hard to make possible. She might not have wanted to come, but that choice should have been up to her. Second, I am fascinated by the way my distorting memory shielded me from this realization. Twenty years later, I asked Mary where she sat at the wedding, and she told me she had not been there. “It was the times,” Mary said. What else am I remembering wrongly, and whose oppression does my amnesia serve?

Early in your marriage, after the birth of your first child, you experienced postpartum depression. You eventually connected with a circle of women in Cambridge and an amazing turnabout occurred. Please tell us about the period leading up to Our Bodies, Ourselves, and your role in the groundbreaking book?

I can answer your good question best by showing how my experience of postpartum depression took me to the creation of Our Bodies, Ourselves.

Postpartum depression was a turning point for me, a gateway. In the months after my son was born in 1969, instead of being a “happy” new mother, I dragged myself around. When he napped, I lay on the living room floor, dreading the little sighs and whimpers of his waking. Ashamed to show friends how down I felt, I tried speaking to the doctor who had delivered my baby. Across his wide expanse of desk, I searched for words to tell him how I felt. The doctor laid a hand on mine. “Don’t want too much,” he said, patting. “Get out to a library once in a while, keep your mind fresh, but be satisfied. You are raising a new generation. You are taking care of your husband when he comes home from a busy day.”

At my first meeting with the women who would soon create the early newsprint edition of Our Bodies, Ourselves, a woman named Paula told the group that she felt depressed for months after her first baby was born. She couldn’t seem to get active, she said; she felt drained, worried, and afraid. She was describing my experience! Many doctors dismissed postpartum depression as the “baby blues,” Paula said, but the condition was caused by hormonal changes and social isolation and could be serious. She was doing research on this condition; she wanted to offer information and understanding to other women.

This was dizzying news to me. What I had been feeling had physical and societal causes. The nuclear family was a lonely place for mothers. Feeling depressed wasn’t my fault. I felt a glimmer of elation, as if a heavy tarp had been lying across my spirits and these women had lifted an edge, letting in light and air.

My life so far had brought me no conscious suffering. I had wealth and health, an able body, private education, and blond-haired, blue-eyed whiteness to smooth my path. Yes, my parents drank and fought, and my mother hid bruises beneath her fancy cashmere sweaters, but I kept quiet about this violence. I did not let this personal pain open a door to connection with anyone else. When caring for a newborn surprised me with its own variety of pain, I found myself in a circle of women who sought to tell each other new truths. With them, I was able to let my small experience of motherly distress “raise my consciousness” about more than my own misery. With their help, I learned that my depression was part of a larger social picture—the isolation of mothers in the nuclear family, the loneliness of parents separated by rigid sex roles, the paternalistic sexism of many doctors to whom new mothers turned for help.

I joined this circle of women to keep learning and to work for change—in medical training, in workplace support for new families, in fundamental assumptions about what’s “normal” and what’s “right.” We wrote up our factual research in the context of our own and other women’s experiences, as well as the politics of health care in the US. The result was Our Bodies, Ourselves. I have been active with this group—my sisters—for more than fifty years.

Aha! experiences like mine are at the heart of the social change fostered by the women’s movement.

Through its values of simplicity, pacifism, integrity, community, and equality, you were drawn into the Quaker faith. At the time you were also traveling in feminist circles, studying African American writers of both sexes, involved in women’s health activism, attending seminary, and still speaking and working with the Our Bodies, Ourselves movement. In the midst of all this, you write, “I found myself adapting the traditional spiritual practice of ‘devotional reading.’ My devotional reading for the rest of my life would feature, not the Bible and other more traditionally religious texts, but writings that increased my understandings of Black American history and culture, and also of white racism, white privilege, white supremacy. Over time, this devotional reading evolved into what I have come to call ‘restorative reading.’” What a wonderful term or expression. Can you talk about the role reading has played throughout your life?

First of all, you mention Quakers in your question, and I want to let Foreword readers know that, over the thirty years after Mary suggested that we write a book, I worked on These Walls in response to what Quakers call a “leading.” A “leading” is a nudge from the Spirit of Love to do something that might be utterly daunting but that one is meant to take on. This leading, and the devoted support of a small circle of Quaker women, kept me going when obstacles loomed. The leading kept me turning back to Mary to make sure I was creating her “character” in the memoir as accurately and richly as possible. In the present time, the leading keeps me doing all the unfamiliar jobs that turn out to be necessary to “promote” a book—that is, to let potential readers decide whether reading it might be illuminating or useful for them. Thank you for helping me with this job through your questions! And now, to your great question about the role that reading has played in my life.

I’ve always thought that my father, who was born into a family where no one had gone to college, remade himself through reading. He got himself into Dartmouth College from a high school in Queens, and made a point of reading all the classics in English literature—mostly, that is, books by affluent white British men. He emerged from this reading prepared to enter the upper class—he attended law school, became a corporate lawyer, and married my blue-blood mother. In the Princeton, NJ, house where I grew up, the den contained shelf after shelf of novels by the British “greats,” all with the drab and unadorned covers that let me know he had purchased them for pennies during the Great Depression.

In my twenties, to my dad’s dismay, I turned away from the upper-class white world he had so desired and worked for. More like him than I even knew at the time, I, too, remade myself through reading. I remember the first book that changed my life, a slim puce paperback by Howard Zinn called Vietnam: The Logic of Withdrawal. I remember the puppy-nibbled arm of the sofa where I sat reading Zinn’s early book, in the summer of 1968, how I’d never before thought that US imperialism was anything but bringing democracy to the world.

There’s another book from that time that could also have changed my life, if I had read it. During my sophomore year at college, shortly after I said “yes” to marrying my preppy boyfriend, a friend who had left college to get married and have a baby gave me a copy of Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique as an engagement present. I told myself I was too busy planning my wedding to read it. Friedan’s warnings about sexism, and the utter depression and disappointment of upper-middle-class white housewives, was lost on me.

But I had majored in English in college, I loved reading fiction, and when I began through multiracial feminism to understand there was a whole world out there that I’d been taught to ignore, I went for the fiction. In the 1970s and ’80s, there were more fabulous novels by current and past African American writers than I could even begin to sample, and a new era of remaking myself began. I call this reading “restorative” because I can read, and learn, from African American writers without blaming myself for racism, or feeling uselessly guilty. This reminds me of the South African “restorative justice” context, in which white perpetrators of horrible abuse to Black people during Apartheid are invited to acknowledge and restore rather than going to prison. Through restorative reading, I can also study what I need to know without leaning on Black friends or colleagues to spend their precious discretionary time teaching me.

In These Walls Between Us, I lift up books by several of the writers whose work has illuminated me, as a kind of fact-checking on any self-serving memory lapses, and to provide a more accurate context for the story of sixty-five years of friendship between Mary and myself.

You also confronted your lesbian identity in the late seventies, as a single, full-time mother. And, with tender shyness, you admit to longing for a loving, physical relationship with a woman. In light of your many amazing experiences and roles, will you help us understand your evolving sense of identity at this time—feminist, best-selling author, Quaker, lesbian, affluent white woman, mother, and more? Is “identity” important?

There’s identity—who I experience myself to be, the many parts and aspects of the whole me that I want to affirm and to have the world respect and affirm. And there’s social location—what worlds walk into a room with me, worlds of class and racial background, for example, contexts that have shaped me in ways that I need to acknowledge and be aware of as I interact with other people. Both are important. One’s identity is precious. Awareness of one’s social location is absolutely necessary.

You’ve spent a lifetime recollecting incidents and conversations with Mary in the light of white supremacy culture, reexamining the countless ways you interacted with her that confirmed the roles you both played over sixty years. This painstaking introspection is admirable, to say the least. Additionally, in great detail, you also describe your relationship, and Mary’s, with your alcoholic parents, the abuse and dysfunction, racism and sexism. My question relates to the writing process. How did you feel when you finally put down the pen and sent the book off to be published?

So many times I thought the book was done, and then realized I had missed key elements of Mary’s experience and/or my own necessary learning. Finally, I reached my late seventies and Mary turned eighty. We realized that, for the book to get out there in our lifetime, this was the moment. After Mary’s two adult sons gave These Walls Between Us a green light, I pushed “send.” My feelings? Gratitude, worry, hope. Mary remembers her feelings when holding the published book in her hands for the first time: “Is it really done? It had been so many years in the making and reading different versions and wondering if we really want it out there. I am in awe.”

I feel fortunate to have found the excellent indie hybrid She Writes Press. The few mainstream presses and agents I had approached were understandably wary of a book written primarily by a white woman about someone who had done domestic work for her family. Although I worked to upset every trope, stereotype, and nostalgic self-indulgence involved in many such books, how were the publishers and agents to know? I had the resources to approach a hybrid press, and so, finally, I did. Brooke Warner read the manuscript, made me shorten it by ten percent, had a beautiful cover designed, and took a chance on These Walls Between Us. I am grateful.

Please tell us what your life is like today? Are you writing? How is your relationship with Mary?

Mary and I talk on the phone or text each other a few times a week. We talked daily during the long years of COVID shutdown, and supported each other to get vaccinated and to stay safe. A new evolution in our friendship has come through invitations from book groups and interviewers to appear on Zoom together, Mary from Virginia and I from Massachusetts. Mary and I plan for, carry out, and reflect on those engagements, and, believe it or not, we learn things about each other that we didn’t know, even after sixty five years. Still in sync politically, we vent passionately with each other after watching the news. We witness the erosion of voting rights in this country with dread and anger. And, finally, my spouse, Polly, and I savor a yearly visit to Mary in her gracious Virginia home, where Mary and I still spar over who is going to wash the dishes.

Okay, how else do I end a conversation with one of our country’s legendary feminists and women’s health advocates without bringing up the recent reversal of Roe v. Wade. Where did your thoughts go when you heard the announcement?

First I felt appalled and angry. Then three thoughts: 1. Organize! We have to keep this crucial option available to women and for the doctors who care for us. 2. Help children! It is cynical and cruel to force more children into the world when we as a country fail miserably to provide the social supports that families need. 3. Hold men accountable! As a sign from a recent rally read, “Blame Dick, not Jane.” Unwanted pregnancy happens too often because men pressure women to have sex (or unprotected sex) and won’t take no for an answer. The Dobbs decision penalizes women for the sexism that gives men the power to pursue sexual release whenever and however they want it. How about a campaign among men to “zip it up!”

Matt Sutherland