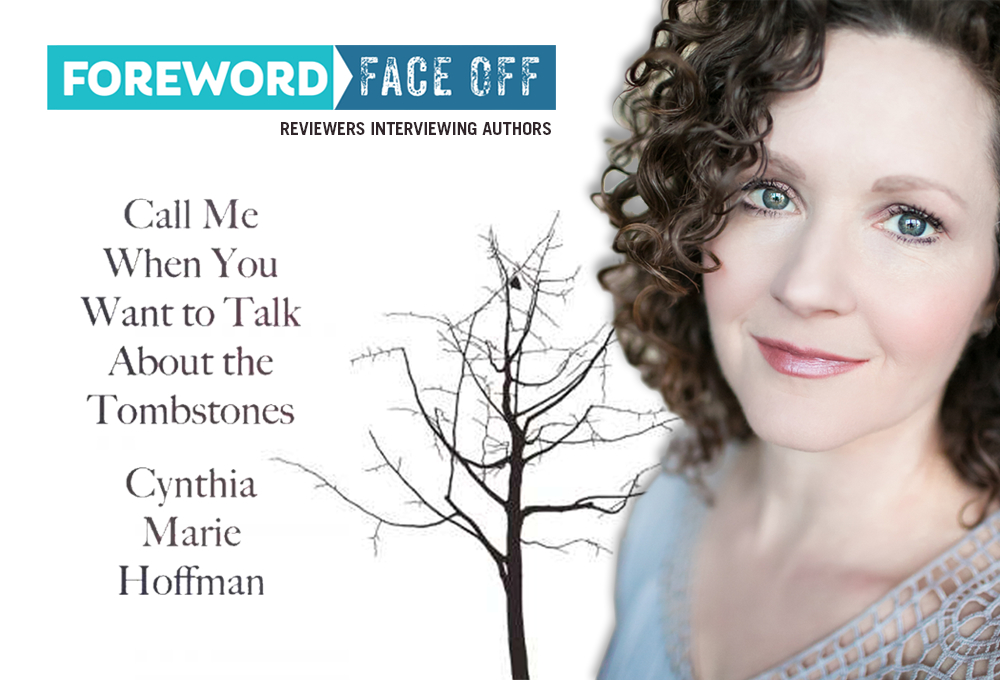

Camille-Yvette Welsch Chats with Poet Cynthia Marie Hoffman, Author of Call Me When You Want to Talk about the Tombstones

There’s countless ways to assemble a collection of poetry, and there’s also the logical way: immerse yourself in one stimulating subject and use the poetic form as your method to ponder and explore.

This week’s conversation is with Cynthia Marie Hoffman, an expert in the discipline of project books of poetry. In Call Me When You Want to Talk about the Tombstones, her third collection, Hoffman did a deep dive into her family’s ancestry, and the “effect is an echo chamber of family—mothers and daughters, grandmothers and uncles speaking across the divide of time, linked by the remains—tombstones, houses, census records,” in the words of Camille-Yvette Welsch in her review for the July/August issue of Foreword Reviews.

Welsch was so smitten with the collection, she pitched us with the Face Off idea and we quickly agreed. Enjoy!

You have two previous books, Sightseer and Paper Doll Fetus, which also operate as project books. What is your attraction to the genre? What does it offer you as a writer?

I believe there is never just one poem to be written about any one subject; often, the first poem just scratches the surface. Ever since I became “serious” about poetry, I have been fascinated with how a poet, who typically writes small things, builds a larger body of work—brick by brick. The more poems I write, and the longer period of time I spend with a subject, the deeper the dive.

And in the case of Call Me When You Want to Talk about the Tombstones, there was such a sheer mass of genealogical research, so many rich lives of my ancestors on the family tree, one poem could never hold it all. Even a book of poems leaves me feeling there is still more to discover.

My attraction to the project book as a reader is akin to my attraction to longer prose forms such as memoir and novels: I can settle down with it and experience full immersion.

As a writer, the project book offers me a “home” to return to. Instead of flitting about from idea to idea, having to come up with a brand new topic every time I sit down at the desk, the subject is already there and waiting. I’m writing travel poems! I’m writing about fetuses and the history of midwifery and birth! I’m bringing my dead ancestors back to life! I can simply pick up where I left off the last time.

And, though it may seem as if poets who write traditional collections on a range of different topics are, as I said, “flitting about,” a deeper analysis of their work will often reveal just one or two primary themes or motifs that resurge again and again—a certain questioning or belief about the world that we seek to communicate or understand. Writing a project book brings that realization into the conscious forefront of the writing process.

You often take history and make it new for the reader, both here and in your other books. Can you talk about that process of turning your family history into poetry?

Because these poems chronicle my genealogical quest to know the lives of my ancestors, the book itself is a sort of historical account of how history is written. Both the history of my ancestors and the history of my discovery of them are documented here.

At times throughout our research, my mother and I made mistakes, read things incorrectly, got confused. We suddenly believed the “Grandfather” in the photo was a particular man, and then we learned he wasn’t. The ghost appeared in my room plain as day, and then he was gone. That sometimes fumbling process becomes a new “third” history in which both the past and the present commingle.

And there is such an interesting tension, a musical one to my poet’s ear, in the cacophony of voices that arises from the commingling of past and present—the flourishing and formal written word from the 1800s versus the chatty and colloquial language of present day.

One of the primary themes I return to in my work is questioning how do we live both in the present and in the past at the same time? How can we live without forgetting? There always seems to me an unknowableness about history, and our attempts to know it, to interact with it, are how we make it new. How we remember the dead. And by writing it down, hopefully how we are remembered.

Genealogy plays a big part in this book. You sift through names and papers and try to piece together what may have happened. How does that link to the way that you craft a poem? Did intertwining the two disciplines change the way that you wrote and engaged with the poems?

The way I wrote this book was different than the way I’d written anything before. Your words “piece together” perfectly describe not only the genealogical research process but also the writing process. The many phrases and scraps of history that comprise this collection began as just that—bits and scraps of notes in a notebook. I typed them up, printed them out, cut them into hundreds of strips of paper. Each strip was a singular idea or unique voice.

I assembled these strips of paper on a card table by theme as if assembling a chorus of voices for a song about fire, tombstones, floods, the Shannon house, the evil brother. Often, the diverse snippets of voice were unmistakably attracted to each other as if by magnetic (or familial) force, and thus the collection took its shape.

The material I had gathered was all a jumbled mix—today and yesterday, the living and the dead—and the structure of the book purposefully attempts to mirror this. That’s another reason these poems are written as prose. Line breaks would have lent the collection more structural authority than befits the content. It was more important for me to recreate the raw experience of encountering scraps of history than to write a tidy poem about that history.

Your mom threads through the volume as she is your companion in this venture. What was her response to seeing herself in your work?

Mostly, she is flattered. This book was a gift for her.

I didn’t know when I was writing it whether it would be published for others to read. And it is therefore the only thing I have written that is so raw and completely unaffected by the ordinarily ever-present critical voice in my head.

I wrote it completely without my mother knowing, and when I finished, I mailed it to her in an envelope. When it arrived, she called me, surprised. Grateful.

A number of years have passed since then, and the book is now a real thing out in the world for others to read. My mother couldn’t be more excited or proud to be such a big part of “our” book. But she admits she’s slightly reticent about the “silly” parts. “Did I really say that?” she moaned to me, once she had a copy of the final published book in her hands. “But that’s my favorite part!” I protest.

She’s not sure how I recalled so many things she said while we traveled and researched. But I simply had a tiny notebook in which I noted a few magical or funny things she would say now and then on our travels or on the phone. We live 800 miles apart, and I was already furiously taking notes to follow along with the flurry of research she was conducting. Often, she would call and read from letters or articles she had discovered from the 1800s and interrupt them with her own commentary. Those phone calls were my favorite.

And then, when I had started to think purposefully about gathering material for poems, there were the dozens of emails to sift through. In fact, the title, Call Me When You want to Talk about the Tombstones, was taken from the last line of one of my mother’s emails.

Most of all, I wanted to capture my mother’s spirit, her way of speaking, her voice. I wanted it to really be her. I feel she is very vivid and alive on these pages. I wanted to give her the gift of knowing she will be remembered. I think I have done that.

In the section, “Corpse Under Local Excess,” a mother writes of her child, “It actually rained here today. Robin and I felt like going out and standing in it.” Though it is in the voice of an ancestor, it could also be yours as your daughter is also named Robin. How has writing this book, reading family history, sharing the genealogical search with your mother and daughter made you think about the legacy of women in the family?

The young girl named Robin (also my own daughter’s name!) in this section is actually my Great Aunt Robin (my grandfather’s sister). My daughter’s name, Robin Anne, takes from women on both my side and her father’s side of the family. And although my daughter is young (she’s eight now), she has quite a strong sense of ancestry and lineage, at least more so than I had at her age. She is aware that we are doing research on our family, she has seen the pictures and the faces of her family who lived long ago, and she is vaguely aware that one day, her great great grandchildren will do research on her. She talks about the things that represent memories and how we research lives by the few small things we keep (a razor, a set of glasses, a container of fresh water pearls, a nightgown).

That awareness, given at a young age, is a sort of legacy—and a responsibility—I feel we are passing down through the generations. I am learning it now through my mother, and I am gifting it on to my daughter. Rather than being scared of death and loss, we can provide comfort by teaching active remembrance.

You weave the language of other people into the book as well as former family homes, black and white pictures, and newspaper clippings. Why did you opt for this multi-media approach?

The inclusion of pictures and clippings was a late addition to the printed book, not something I had imagined possible during the drafting stages. I am thrilled that some of my family members’ faces will get to be seen by readers, especially those of Samuel and Kittie Shannon—who, as the poems say, “really are the main people”—and their ivy-draped home. And, that readers will get a small taste of the actual documents my mother and I were discovering.

Once Persea Books decided a multi-media approach was possible, I was set with the task of matching actual pictures and clippings to what I call the “caption” poems—the small prose poems that interact with or describe these documents. This was a breeze in cases where the caption is based on a specific, existing document. But some documents don’t exist, or they are things I had simply imagined. Imagining a new document was fun and liberating during the writing process, but it was a challenge during the publication process. In some of those cases, I included a document instead of photo, such as a letter recounting an event that occurred in the 1700s when, of course, there couldn’t have been an actual photograph.

And in other cases, it was more interesting to present a photograph that communicates with the caption in a way that layers meaning without directly illustrating what the poem already says. My favorite example of this is the photograph of my grandparents sitting together on the beach when they were young, both in profile and looking into the distance across the ocean. Beneath it, the caption poem describes a diagram of my elderly grandmother’s heart and ultimately, my grandmother’s passing. The actual diagram does exist, but the photo of my mother’s mother, sitting with the man she loved, is far more compelling.

If you could pick a line from this book as the book’s epigraph on a proverbial book tombstone, what would it be?

It would probably be one of the two epigraphs in the book “What if I croak before it’s done?” which is something my mother said.

It is everything this book is about: at once the desperation of grappling with our own mortality, the sense that we are running out of time to do all the things we wanted to with our lives, but also the certainty that we all one day “croak,” and that we are never done with the world before we are made to leave it. It tugs at my heartstrings with its urgency.

Camille-Yvette Welsch