Celebrate First Woman Presidential Nominee with Feminist History Books

Late July, 2016: when the American political landscape changed forever, and Hillary Clinton, following a path set by Shirley Chisholm and other brave women who insisted upon change, became the first woman to accept a major American party’s nomination for the presidency.

We who live for cutting edge books cannot help but be moved by these monumental cultural shifts—particularly when they’re ushered in, as Hillary’s nomination was, by speeches celebrating reading itself, and the new landscapes it opens. Chelsea Clinton located her own dawning awareness of the world’s possibilities in trips, with her mother, to the library; we agree that public stacks are a site of enormous potential. That curiosity that begins with a book can lead somewhere revolutionary.

In recognition of the fresh realization that women, too, can be the one’s who lead us, and to honor the fact that those options sometimes become clear in a book: we nominate these great titles on feminism and women’s progress for your must-read stacks.

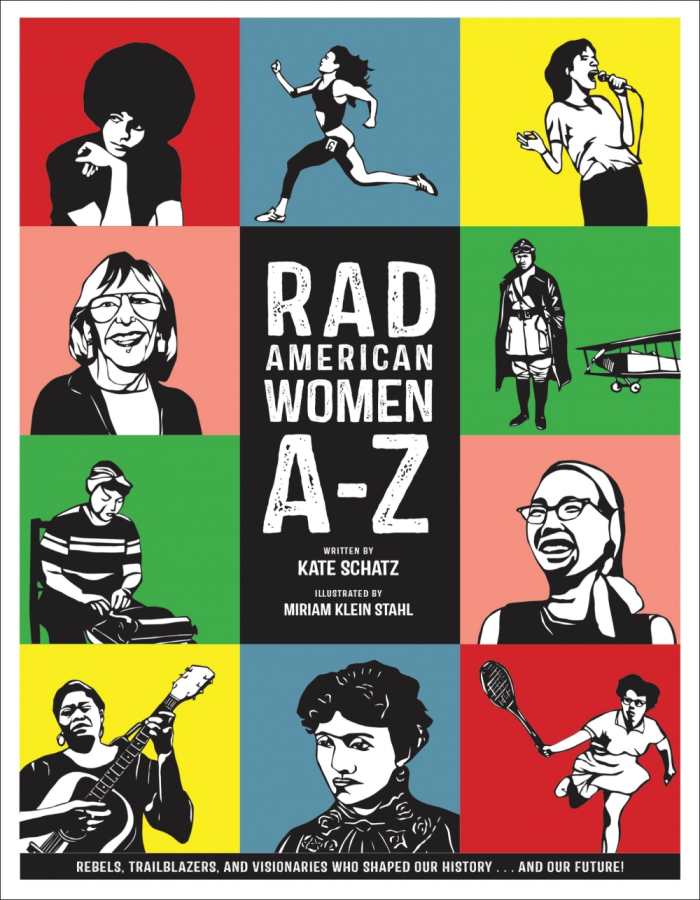

Rad American Women A–Z

Rebels, Trailblazers, and Visionaries Who Shaped Our History … and Our Future!

Kate Schatz

Miriam Klein Stahl, illustrator

City Lights Publishers

Hardcover $14.95 (64pp)

978-0-87286-683-6

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Angela Davis. Billie Jean King. Carol Burnett. The first three women in this fantastic ABC book set the tone for what’s to come: visionary, bold, diverse role models for an array of children today. Each page, with a modern illustration, a brief biography, and an uplifting overview of her accomplishments, will inspire young world-changers both in social studies classrooms and at home. Ages eight and up.

AIMEE JODOIN (February 27, 2015)

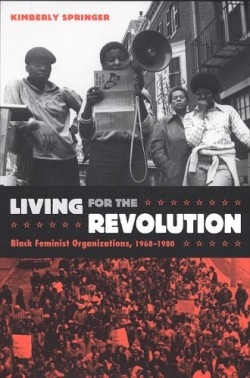

Living for the Revolution

Black Feminist Organizations 1968-1980

Kimberly Springer

Duke University Press

Unknown $22.95 (240pp)

978-0-8223-3493-4

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Black feminist organizations are an appropriate place to begin chronicling the history of African American women’s social clubs. Though clubs have been in existence since the nineteenth century, the author focuses her study on five contemporary black feminist organizations, all of which were organized by 1968 and defunct by 1980: the National Black Feminist Organization, the Combahee River Collective, the Third World Women’s Alliance, Black Women Organized for Action, and the National Alliance of Black Feminists.

Springer, who is also editor of Still Lifting, Still Climbing: African American Women’s Contemporary Activism, has written numerous articles about black feminism for anthologies and journals and is a lecturer in American Studies at Kings College, University of London.

For quite some time, black women have been in a precarious position regarding the politics that are of interest to them. Active in civil rights organizations, they have been asked to ignore sexism and other gender-related concerns in order to focus fully on the race question. These established organizations allowed few opportunities for black women to assume leadership roles or to nourish their attempts at activism. Some black women, though skeptical, turned to white feminist organizations, but quickly learned that mainstream feminism was not eager to take on the concerns of women of color. At the core of black feminism is the idea that black women are multiply oppressed by race, gender, and in some cases class and sexuality.

Interested in both civil rights and feminism, black women formed their own organizations determined to do the work that mattered to them. The five organizations studied took an anti-racist and anti-imperialist stance and confronted sexism, heterosexism, and other forms of discrimination in the United States and in Third World countries. They challenged racial and sexual stereotypes of black women (and men and children) in the media, low-wage domestic positions for black females (including some college graduates), unequal pay, forced sterilization, and general health-care issues.

Using interviews with key figures like Francis Beal and Barbara Smith, and organizational documents such as newsletters, files, and calendars, Springer describes how and why these organizations were started, including their objectives, accomplishments, and demises. Maintaining these organizations beyond twelve years proved difficult. Black feminists learned that black women are not monolithic. They too hold a variety of ideas about class, educational attainment, sexuality, and other topics. Internal “challenges” related to differences in ideology, difficulty securing adequate funding, and unequal distribution of responsibilities contributed to the demise of the organizations.

Though it often reads like a doctoral dissertation and is a bit repetitive throughout the six chapters, Living for the Revolution proves that these organizations have left comprehensive maps, which black feminists can make use of today and in the future. Who knows? Despite the different ways that black feminism(s) are practiced, there could be new contemporary black feminist organizations in the works.

KAAVONIA HINTON (August 18, 2009)

Imagining Ourselves

Global Voices from a New Generation of Women

Paula Goldman, author, editor

New World Library

Softcover $26.95 (239pp)

978-1-57731-524-7

They’re the best educated, most professionally successful, internationally attuned generation of young women in history, and there are more than one billion of them living in 193 countries, speaking more than six thousand languages. Yet, women in their twenties, thirties, and forties remain the most unrecognized and unappreciated population group on the planet.

The editor of this anthology is one of them. In the fateful fall of 2001, Goldman was armed with a Harvard master’s degree in public policy and little else, save a dream of making a difference in the world. Having worked and traveled internationally, Goldman knew women just like herself who were doing precisely that—taking the initiative to change their own lives and help others improve theirs, despite overwhelming odds and often in the face of cultural and political antagonism. There were, she thought, countless stories to be told, and so, working in conjunction with the International Museum of Women (IMOW), Goldman sent out a call for submissions of artwork and writing that would answer the question, “What defines your generation of women?”

The response was staggering: more than 3,000 replies and 800 formal submissions were received from women representing approximately one hundred countries. The most inspiring and thought-provoking entries are gathered in an electrifying book that showcases the creative talents, celebrates the diversity, and illuminates the political, social, and economic challenges this generation of women are facing and have overcome. The keystone of the IMOW’s “Imagining Ourselves” project, the book, along with an interactive online exhibit, unites the woman in the next cubicle with the woman on the next continent. From Albania to Zaire, their commonality lies in their commitment to change, whether as a person or as a member of society.

Some of the 105 contributors are well known: British author Zadie Smith, American singer Ani DiFranco, former Russian Olympic figure skater Oksana Baiul. Most, however, are not, but to call them “ordinary” or “typical” would be a disservice. From Nigeria’s Hafsat Abiola’s interview with a young woman sentenced by an Islamic court to death by stoning for having a baby out of wedlock, to Malaysia’s Yee-Ming Tan, director of Third Thinking, a corporate culture consultancy, the women are remarkable for the depth of their determination and their unbridled optimism in the face of continued violence, oppression, and poverty. Through their paintings and poems, sculpture and stories, they speak to diverse issues of motherhood and beauty, crime and disease, racism and sexuality.

“As a generation of women,” says Kenya’s Naomi Wanjiku, “we have limitless possibilities. Once we have made achievements as individuals, it will dawn on us that we are all one large, beautiful quilt, made of individual stitches.”

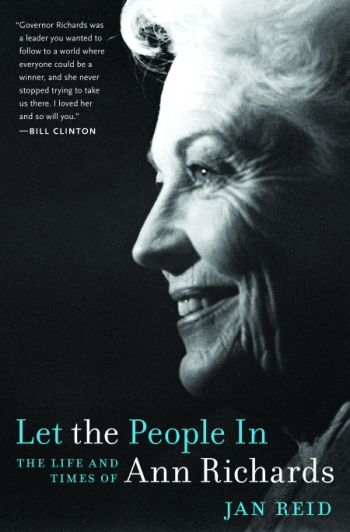

Let the People In

The Life and Times of Ann Richards

Jan Reid

University of Texas Press

Hardcover $27.00 (460pp)

978-0-292-71964-4

When Ann Richards was elected governor of Texas in 1991, she ushered in a “New Texas” by appointing large numbers of women and minorities to government positions. True to Richards’s feminism and progressivism, she “let the people in,” which biographer Jan Reid claims was the politician’s greatest accomplishment. The author presents a compelling history that not only tells Richards’s story but also provides a revealing view of the Lone Star State’s unique brand of politics. The author of eleven previous books, including two award-winning novels, Reid researched this account deeply, plumbing the Ann Richards archives at the University of Texas and conducting more than two hundred interviews with her family members and coworkers.

Born Ann Willis in 1933, her impoverished parents worked hard and, with scholarship aid, sent their daughter to local Baylor University, where Ann’s high school sweetheart and future husband, David Richards, also matriculated. By 1963, Ann Richards was a stay-at-home mom raising their four children while volunteering for the Democratic Party. Reid’s story of how her subject’s alcoholism and failing marriage led to her decision to enter rehabilitation is gripping. This experience later encouraged Richards to introduce rehabilitation programs for prison inmates.

Both Richards’s 1984 nominating speech for Democratic vice presidential candidate Geraldine Ferraro and her keynote speech at the Democratic Convention four years later were career-changing events, claims the author. After squeaking by former governor Clayton Williams in a bitterly fought battle for governor in 1990, Richards’s single term was a success for the first two years followed by controversy during the last two. Prison and insurance reforms and environment preservation highlighted the good years, but scandals and vetoing a bill that would allow citizens to carry concealed weapons made her vulnerable to a Republican challenge in 1994. She was routed in her bid for re-election by George W. Bush, who felt a special vindication for Richards’s earlier remark that George H.W. Bush was “born with a silver foot in his mouth.” Ann Richards died in 2006 at age seventy-three from esophageal cancer and is remembered as a mentor for many women politicians, including Hillary Clinton.

Although Reid at times includes too much detail, mostly about the 1990 gubernatorial campaign, and does not include a summation of Richards’s career and legacy, this account of the woman, her times, and rough-and-tumble Texas politics will engross informed general readers, political junkies, and feminist and political scholars.

KARL HELICHER (December 3, 2012)

The Feminist Utopia Project

Alexandra Brodsky, editor

Rachel Kauder Nalebuff, editor

The Feminist Press

Softcover $19.95 (384pp)

978-1-55861-900-5

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

This inspiring and thoughtful anthology imagines a world where women’s bodies, minds, and beliefs are undoubtedly respected.

If feminism is the belief that men and women should have equal rights and opportunities, what would that the ideal society really look like? With the thought-provoking The Feminist Utopia Project: Fifty-Seven Visions of a Wildly Better Future, you can leave pay inequality, harassment, glass ceilings, and sexism behind and wander through a world where women’s bodies, minds, and beliefs are undoubtedly respected.

For the inspiring anthology, editors Alexandra Brodsky and Rachel Kauder Nalebuff asked their peers of activists, journalists, and artists, as well as the public at large, to sketch out scenarios where feminist dreams are fully realized. “We want more,” the editors write in the introduction to the collection of essays, stories, poems, and artworks. “[But] how can we dream big when are constantly playing whack-a-mole with the patriarchy?” So the editors implored the contributors, which include television writer Jill Soloway and trans activist Miss Major Griffin-Gracy, to put down their mallets momentarily and start dreaming.

In Gloria Malone’s “Feminist Utopia Teen Mom Schedule,” the high school has an on-site daycare where the a teen mom can visit and breast-feed her baby. In “Not on My Block,” a picture of life without street harassment, Hannah Giorgis writes of not having to choose between a prohibitively expensive cab ride and walking home with the risk of violence from men. In one of the anthology’s several interviews, a high-school teacher imagines a world in which sex-ed classes include the history and politics of reproductive health and students would speak with a pharmacist to really understand how oral contraceptives work.

What’s more, The Feminist Utopia Project is thoughtfully organized to avoid creating a hierarchy of topics or contributors, and the layout reflects its utopian vision right down the typefaces used, which were, of course, designed by talented women.

In total, the works are poised to “ignite your feminist imaginations to help you dream bigger and weirder and inspire our movements to greater collective ambitions,” in the editor’s words. It’s a welcome relief to spend a little time in a place where rampant gender inequality seems like a bad and distant dream.

AMANDA MCCORQUODALE (November 27, 2015)

The New Feminist Agenda

Defining the Next Revolution for Women, Work, and Family

Madeleine M. Kunin

Chelsea Green Publishing

Softcover $17.95 (288pp)

978-1-60358-291-9

As the first female governor of Vermont, and a lifelong feminist, Madeleine M. Kunin brings a wealth of knowledge and authority to her latest book, The New Feminist Agenda. Convinced that feminism has not lived up to its potential, Kunin seeks to infuse the movement with new vigor by redirecting its focus. And so she asks: “Can we mobilize under the banner of Feminists for Families?”

And by “we,” she pretty much means everyone. “We need a revolution,” writes Kunin. “But women cannot lead it alone. We have to broaden the feminist conversation to include men, unions, the elderly, the disabled, religious groups, and the unaffiliated.” What she suggests is that feminists broaden their ranks so that they may “snatch back the words ‘family values’ and redefine them as the work/family policies necessary to sustain strong families.” In particular, Kunin calls for the institution of work flexibility across the board, for all men and women, wealthy and poor.

Kunin looks to other countries for case studies where the institution of maternal/paternal leave and work flexibility has been successful. She investigates the more radical policies of the Nordic and European countries, as well as the policies of countries similar to the United States, including the United Kingdom and Canada. Her line of inquiry not only details the policies of these other countries but also asks, “Would this work in the US?”

In studying the states that have successfully passed family leave policies (California, Washington, and New Jersey), Kunin details the lessons learned from those situations so that similar laws might be implemented elsewhere. The conclusions might seem simplistic or obvious—for example, “form a broad coalition,” “frame the question,” “do not accept the inevitable”—and yet, the work Kunin is doing here is important. She’s not only framing the conversation but also bringing a new generation of feminists into a discussion in which they may have never before played a part.

Though at its heart this is a feminist manifesto, it’s not a polemic. Rather, The New Feminist Agenda reads like a practical guide, loaded with case studies and examples, all of which invite even the casual reader to consider that the “next revolution” may be not only definable but also attainable.

OLINE EATON (May 31, 2012)

A Little F’d Up

Why Feminism Is Not a Dirty Word

Julie Zeilinger

Seal Press

Softcover $16.00 (256pp)

978-1-58005-371-6

It seems that every few years, feminism gets a new literary paint job. We’re now in the era of “third wave” feminism, with a strong focus on criticism of gender stereotypes and media portrayals of women. In academic circles, this wave involves elements like postcolonial theory, ecofeminism, transgender politics, and queer theory.

Although discussions centering around those themes are useful to pursue, first-time author Julie Zeilinger prefers a different route: focusing on the essentials of female empowerment and appealing to the young women who will form a crucial “fourth wave” before long.

She talks to these teenagers like she’s one of them because she is. She begins her witty book with: “So. I’m a teenager and I wrote a book. And not just any book. A book about feminism. What kind of obviously pretentious and generally ridiculous teen does that?” The answer: a very talented one.

Zeilinger’s wry, conversational style works exceedingly well at making her opinions and research accessible to a wide audience, particularly young adults. She titles a chapter on feminist pioneers “The Badasses Who Came Before Us” and breaks down complicated milestones like the Equal Pay Act and Roe v. Wade. She’s not afraid to throw swear words around, but she also elevates her writing with complex insight.

Particularly significant, she argues for new language around the word feminist, noting that although it’s not a dirty word (as denoted in her book’s subtitle), the term has taken on negative connotations that are difficult to avoid. She manages to describe the difficulties of language without becoming ensnared herself, proving to readers that words have power, which turns out to be her larger point.

Often, she’s like an adult Alice, giving a tour of Wonderland to younger girls, with the promise that they’ll inherit all they see as long as they don’t drink from the poisoned bottle of misogyny. As a tour guide, Zeilinger brings a great deal of experience to the task. Currently a student at Barnard College, her blog for teenage feminists, FBomb, is regularly read by hundreds of thousands of people worldwide, and this work should garner an even broader audience.

Irreverent, fresh, charming, and hugely important, Zeilinger’s exploration of feminism should be required reading for every teenage girl—and passed around by adult women, too.

ELIZABETH MILLARD (May 31, 2012)

A Strong-Minded Woman

The Life of Mary Livermore

Wendy Hamand Venet

University of Massachusetts Press

Unknown $24.95 (319pp)

978-1-55849-513-5

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Upon her death in 1905, Mary A. Livermore was hailed by the Boston Transcript as “America’s foremost woman.” It was a fitting epitaph. During the Civil War, Livermore worked tirelessly to ensure proper nutrition and medical care for Union soldiers. She was a gifted journalist and orator, and commanded private audiences with Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant. At the peak of her thirty-year career, her reputation as a champion of women’s rights rivaled, and perhaps even surpassed, those of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. One hundred years later, the fact that few, if any, Americans have even heard of Livermore is both a testament to her complex character and to the fickle forces that shape celebrity.

The author’s latest book marks the first full-length study of Livermore’s life, a fact due in part to the difficulty of the task. Wary of posthumous biographers who might tarnish her reputation, Livermore burnt all her personal correspondence before she died. Venet nevertheless succeeds in crafting a remarkable piece of research by drawing on Livermore’s two autobiographies and her numerous articles and speeches. Anyone with an interest in American history or women’s history will delight in this fascinating behind-the-scenes look at the incipient U.S. feminist movement and one of its brightest stars.

Venet first developed an interest in her subject as a graduate student of history at the University of Illinois. Her research on the role of women in the Civil War resulted in her first book, Neither Ballots Nor Bullets: Women Abolitionists and the Civil War (University Press of Virginia, 1991). In 1997, she co-edited the anthology Midwestern Women: Work, Community, and Leadership at the Crossroads (Indiana University Press). A book review editor for the academic journal The Historian, Venet is a full-time professor of nineteenth-century U.S. History and American Women’s History at Georgia State University.

At a time when women could not attend college nor lay any legal claim to their own income, Mary Livermore campaigned for women’s acceptance into the Universalist ministry and won. She deplored the dire working conditions in dress factories and celebrated the first woman admitted to the Philadelphia Typographical Union. But her progressivism was not without limits. Raised in a strict evangelical household, the Boston native was slow to embrace social liberalism and in some ways never fully did.

Throughout her life, she remained a staunch critic of alcohol consumption and supported the wearing of moderate corsets. Although such antiquated values may have contributed to Livermore’s fading legacy, they also add depth to her biography. More than just a figurehead for a cause, Venet’s Livermore emerges as a living, breathing woman who both succumbs to and surpasses the times in which she lived.

AIMEE SABO (August 18, 2009)

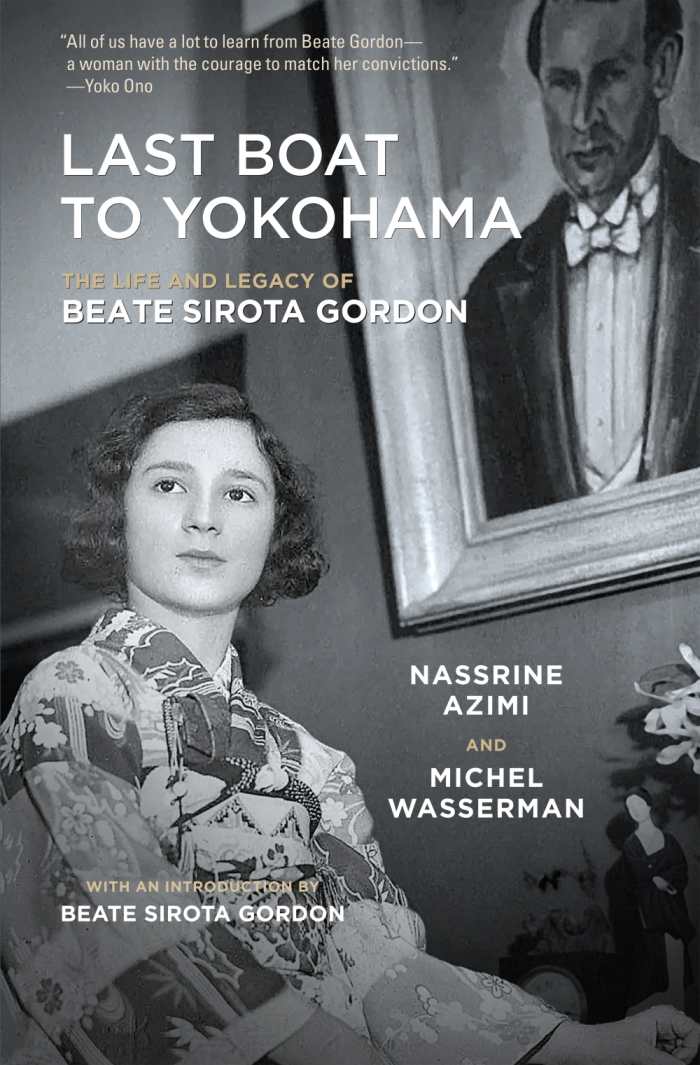

Last Boat to Yokohama

The Life and Legacy of Beate Sirota Gordon

Nassrine Azimi

Michel Wasserman

Three Rooms Press

Softcover $15.95 (170pp)

978-1-941110-18-8

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop)

Women’s rights activist Beate Sirota Gordon’s passion for bridging cultures is clearly evoked through this fascinating tribute to her work.

Nassrine Azimi and Michel Wasserman pay tribute to Beate Sirota Gordon, champion of the arts and part of the American team who developed Japan’s postwar constitution under General MacArthur. Gordon’s story highlights her sustaining belief in making human connections. With a prismatic approach that includes remarks from Associate Justice Sonia Sotomayor, an interview with Gordon, journal entries by Gordon’s mother, and other sources, Last Boat to Yokohama: The Life and Legacy of Beate Sirota Gordon gathers respectful reflections that shed light on a specific moment in history and on one woman’s remarkable career.

At the age of twenty-two, Sirota Gordon penned the words that would mark her as a beloved figure among Japanese women. Last Boat to Yokohama quietly emphasizes the importance of the constitutional article that granted legal rights concerning marriage, divorce, property, and inheritance that hadn’t existed in the once-feudal society. When the authors note how Japan’s postwar constitution has inspired other countries emerging from war, the impact of Sirota Gordon’s efforts is especially felt.

Amid the story of Sirota Gordon’s unlikely role working under the occupation lies an intriguing glimpse at her childhood in Japan, her parents’ experiences during the war, her father’s path as a concert pianist, and Sirota Gordon’s later involvement in bringing Asian performers to the US. Threads spanning the 1940s are particularly compelling for their portrayal of foreigners’ daily lives in Japan. The clear, well-paced writing maintains the focus and interest of a solid, extended magazine profile.

Despite the elegiac nature of such a compilation, the book does not dwell on hardship and consistently reveals its subject’s optimism. Sirota Gordon’s passion for bridging cultures is clearly evoked through accounts of her travels. Last Boat to Yokohama offers just enough detail to inspire readers to seek Sirota Gordon’s own biography, The Only Woman in the Room: A Memoir of Japan, Human Rights, and the Arts.

KAREN RIGBY (May 27, 2015)

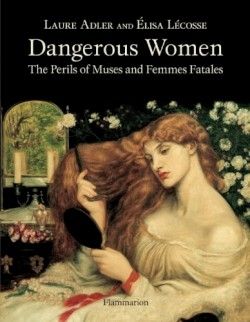

Dangerous Women

The Perils of Muses and Femmes Fatales

Laura Adler

Flammarion

Unknown $39.95 (160pp)

978-2-08030128-4

“History and mythology are full of female figures who made a crucial impact on cultural or political life,” the authors write.

In Dangerous Women, Adler, a journalist and feminist historian, and Lécosse, who holds a doctorate in art history and authored Love in the Louvre, analyze the women who have exerted a siren-like pull on men. More than forty-five women are included, such as sorceress Circe, the brewer of potions; irresistible Esther, the bewitching slave-girl; and infamous Pandora, “a poisoned chalice for mankind.” These character sketches are accompanied and illuminated by 100 color reproductions of memorable paintings.

“This journey through the history of art invites us to examine for ourselves the various metamorphoses of woman in love,” Adler writes in her introduction. She provides perspectives on women which include the “fascination” with virgins, “the instantaneousness of desire,” male/female relationships, and “women with the hearts of men.” The feminist historian illustrates her remarks with references to different portrayals of the Virgin Mary, like the “sexualized virgin” in The Annunciation c.1450 by Flippo Lippi, in which the artist “turns [the Virgin Mary] into a bride.”

Included in the “Seductress and Enchantress” chapter is Viviane, “the Lady of the Lake,” who beguiles from Merlin his knowledge of the arcane. In “Emancipation and Transgression in Love” a metaphor of the dangers of female power is illustrated by Ovid’s nymph Salmacis entangling Hermaphroditus. Boston eccentric Isabella Stewart Gardner appears in “Women and Power,” painted by John Singer Sargent; known as the “serpent of the Charles,” she assembled a collection of men and art. In “The ‘Eternal’ Feminine” is devotee Juliette Drouet, Victor Hugo’s inamorata; even though this actress was betrayed many times by him, she wrote more than one thousand billets-doux to Hugo.

Francesca in “Women in Love” falls for Paolo, the brother of the husband she was forced to marry. In punishment for their entangled liaison they appear in Dante’s “Second Circle,” “so painful that it stings to groan.” The description of Ary Scheffer’s The Shades of Francesca di Rimni and Paolo Malatesta Appearing to Dante and Virgil c.1855 is artfully rendered: “Their luminous, entwined bodies appear to surge up from black depths through which they float ethereally.”

The book’s strengths are its descriptions and interpretations, though Adler’s penchant for rhetorical questions can occasionally annoy. Overall, this book is a provocative marriage of words and image: the selection of illustrative paintings is admirably chosen, and Dangerous Women provides a full palette of feminine power.

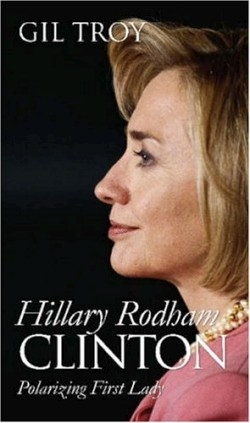

And on Hillary herself, before she was secretary of state—these valuable notes from along the way:

Hillary Rodham Clinton

Polarizing First Lady

Gil Troy

University Press of Kansas

Unknown $24.95 (263pp)

978-0-7006-1488-2

With the exception of Eleanor Roosevelt, no other first lady has stirred as much controversy as Hillary Rodham Clinton. The author says she has “been bolstered by her friends, betrayed by her husband … interrogated by prosecutors, hounded by reporters … and lionized by women throughout the world.” Troy, a highly regarded historian at McGill University and the author of Morning in America: How Ronald Reagan Invented the 1980s*, Mr. and Mrs. President: From the Trumans to the Clintons, and See How They Run: The Changing Role of the Presidential Candidate, presents an illuminating and welcome investigation of Clinton as “the first feminist First Lady.” Troy’s refreshingly unbiased account reveals Clinton’s contributions and excesses and assesses her impact on the institution of the First Lady.

Her introduction to the nation was less than auspicious. It occurred on an episode of 60 Minutes* during Bill Clinton’s 1992 presidential campaign. The interview included probing questions about her marriage that led to an angry retort, which angered country singer Tammy Wynette and droves of working-class women.

Clinton regretfully ignored America’s distrust of powerful first ladies. She tackled National Health Care as a co-president, which contributed to the failure of a national plan and led to a backlash that made her a scapegoat for President Clinton’s failed first hundred days. The author is especially good at identifying characteristics that the public wants in a First Lady. The most popular ones—Mamie Eisenhower, Jackie Kennedy, Barbara Bush, and Laura Bush—avoid policy fights and enjoy the traditional role as the nation’s First Hostess. More outspoken First Ladies, including Betty Ford, Rosalyn Carter, and Nancy Reagan, who downplayed the “traditional gossamer shackles” the position imposes, quickly drew public mistrust with cries of “who elected her?”

During President Clinton’s first term, Hillary became embroiled in Whitewater, Travelgate, and cattle future speculations, while blaming understandable attacks on “a vast right-wing conspiracy,” which made her less popular than her amoral spouse. During Clinton’s second term, Mrs. Clinton became a more appealing First Lady by taking on such projects as establishing the Mother Teresa Home in Washington D.C. and becoming honorary chair of the President’s Committee on the Arts and Humanities. However, she also had to deal with the embarrassing Lewinsky affair and the presidential impeachment.

Troy notes that the public never did support policy roles for Mrs. Clinton but did offer her sympathy for her husband’s philandering and came to admire her for assuming acceptable First Lady responsibilities. Ultimately—as Senator Hillary Clinton has demonstrated—the author concludes that real political power comes from winning elections and not from being married to the president.

KARL HELICHER (December 8, 2006)

Avowed feminist Michelle Anne Schingler is associate editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow her on Twitter @mschingler or e-mail her at mschingler@forewordreviews.com.

Michelle Anne Schingler