Charlottesville Library: Educate the Electorate

White supremacists march near the library in Charlottesville, Virginia. Photo courtesy of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

John Halliday, director of the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library (JMRL), is not sure how to get racists away from what he calls “antisocial networks.” But he knows it needs to happen, because he’s seen the result of those networks firsthand. The JMRL is located right in downtown Charlottesville, Virginia.

When the now-infamous patchwork rally of white supremacists descended in August to chant, attack counterprotesters, and wave flaming torches, the library served in some nontraditional functions:

-

Taker-down of white supremacist bulletins, which had been illegally nailed to their front doors;

-

Opener of doors to tired police officers, who pulled long hours to keep the peace;

-

Securer of Wi-Fi; and

-

Raiser of diversity flags.

These are things they don’t teach you in library school.

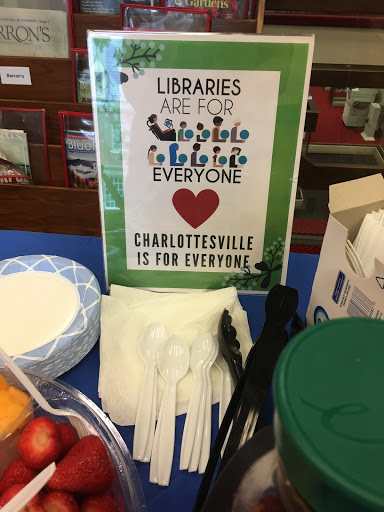

Charlottesville's library welcomes everyone.

What they do teach is that libraries are a democratic resource, a way to educate voters regardless of income or origin or set of beliefs. So, looking at the rally in Charlottesville and the ugly nest of snakes it uncovered, it now falls to libraries, as educators of democracy, to ask two important questions: What happened? And what now? In the words of John Halliday, “How do we get the haters and racists into the library and away from their TVs and antisocial networks?”

Libraries and Democracy

An informed citizenry is critical to the democratic process. If you don’t believe me, then consider the American Library Association’s investment in educating the electorate. According to an enthusiastic pamphlet by the ALA called Smart Voting Starts @ Your Library, “America’s libraries stand at the heart of our democracy as they are among the few public spaces left in civic life that stand outside of the marketplace.” The publication outlines some good ideas about fostering public discourse and making information available to voters, featuring a strong side focus on getting people to vote pro-library in their local communities. Page 8 lists the names and contact info of libraries who are doing it “right.” The tone is optimistic.

This publication predates the first iPhone by about six years.

These hectic modern times have taught us many useful things, but they haven’t made us much smarter. What fascinates the human brain is generally emotional, not factual. Not that the Internet is fully to blame. Libraries were invented to combat the natural human impulse toward reactionarianism when most of America couldn’t even read, much less follow the president on Twitter.

The difference is that up until now, we’ve assumed a certain power on the part of information. If something was true and verifiable, it would trump falsehood. Yet this isn’t necessarily so any longer. As Americans, we now find ourselves in a situation where voting citizens, emotionally invested in their opinions and beliefs, don’t need to find The Truth, just a truth, one that fits their perspective.

Prior to the Internet, isolated wackos might have been easily neutralized by a generally accepted, verifiable truth—-or, at least, by the trusted town paper. Now extreme ideologies congregate on Reddit. Members of the federal government call the newspapers into question constantly. As a result, the very production of objective information has become a political act.

What does this mean for libraries? Unlike newspapers, we’re not engines of truth, but rather of discernment. We don’t tell people what’s real, but instead give them the tools to decide for themselves. Historically, again, this has been fairly straightforward: libraries provided a selection of newspapers and the collected works of Ayn Rand and Karl Marx and called it a day.

But now we’re dealing with online communities spanning entire regions, even the nation, gathering followers online and grouping up like slime molds in real life whenever their numbers reach a critical mass. Could these far-flung groups influence elections? Craig Cobb, white supremacist, certainly thought so when he moved his neo-Nazi group to the North Dakota town of Leith and tried to take over.

America isn’t quite Leith writ large, but it might not take a ton of Nazis to nudge local elections. Remember, voter turnout percentages currently reside at profound depths. A small cohort of like-minded and organized racists, KKK members, or, yes, Nazis might tip smaller towns fairly easily toward candidates with extreme viewpoints. It also seems reasonable to assume that only the stupidest Nazis will show their faces in public; Smart ones might remain undercover, mowing their lawns and showing up to work on time, voting according to their beliefs or even running for office without anyone being the wiser. At least, at first.

Libraries, among other community-based educational institutions, have a responsibility to educate the electorate. At the moment, we’re being beaten—-how badly, it’s hard to say—-by the ghost of a failed Austrian painter.

Charlottesville Library on front lines

Most of us understand instinctively that this is a core piece of our mission, something we can’t give up when the going gets tough. It seems possible—-even likely—-that public libraries will soon be tested on their principles, as was the Jefferson-Madison Regional Library of Charlottesville, Virginia.

“I agree [educating voters] is a high priority,” says Halliday, director of JMRL. During the white supremacist march in Charlottesville in August, the JMRL central branch found itself in the midst of a surreal scene. Police used the library as a recon station. Someone nailed a white supremacist screed to their front door. And yet, they have doubled down on their mission to provide diverse programming. In the days after the march, which featured torch-wielding men attacking counterprotesters, the library displayed a pro-diversity banner in front of their building. They are outspoken about their policies, which prominently support the promotion of diversity, tolerance, and education.

But there are complications now beyond what one library can manage alone. “Unfortunately, the hateful thugs who came to Charlottesville intending to cause harm are not part of JMRL’s electorate,” Halliday said.

It seems doubtful that the racists who briefly invaded Charlottesville are avid library users to begin with, so their home libraries—-libraries across the nation—-would need to woo them independently to even make a dent in the kind of ignorance America saw on the nightly news. Each library would need to take it upon themselves to educate and extricate each individual away from Nazi ideology—-dragging against the pull of online white supremacist organizations—-and into a healthy American mindset of equality and tolerance. Instead of one giant fire of ignorance to stamp out, communities nationwide are confronted with scattered small blazes.

Worse, the Internet is comparatively easy to choose over the traditional library route. A book takes time. A book is uncomfortable. You can’t scream back at it if you disagree. You’re forced to absorb the cognitive dissonance, think about what you read, and decide how you feel in light of new evidence.

Attack Racists with Education

Halliday feels strongly that it’s possible for libraries to get racists into a healthy mindset through new channels. “Many libraries, JMRL included, are providing programming related to evaluating information sources and identifying fake news,” He says. “We need to keep doing more of that—-educating the public to identify accurate information and political propaganda.”

How do we educate an electorate in the Internet age? We teach them what librarians already know: how to be the smartest about information. How to rate it. How to vet it. If a racist has built walls to keep out the truth, we may be able to reach them without activating their mental defenses if we just teach them how to look at data. How to see that their twisted worldview is not just wrong, but toxic to themselves and the nation they claim to love.

Let’s not forget that education itself is a radical act and, in an age when an Internet user can educate themselves to the tune of any half-truth that feels right to them, a charged one. Libraries and schools are among the few institutions equipped with the expertise and tools to tell people that their feelings don’t count as facts. The political mission of a library is to make sure that Americans have the intellectual resources they need to be good voters, and thus libraries have always been, and will always be, political. Sitting this out is not an option.

Yet, as JMRL Assistant Director Krista Farrell points out, libraries don’t need to act alone. “We’re able to stand up responsive programs quickly because of our existing [community] partnerships and building on past successful programming,” she says. The fact that staff are a part of the community in Charlottesville, serving on various boards and councils throughout town, gave the library the support network it needed to push back not just against Nazis, but against ignorance, and do to it with a broad network of support. That support can, and ultimately must, include other educational institutions, schools and colleges and community centers.

Read the rest of our Knowledge Matters series

That’s what’s going to get us through this difficult political epoch. Not shouting. Not lone heroes. Not managing our collections or keeping our heads down or confronting the KKK with catchy handwritten signs. We’ll get through this by cooperating. With community support, it’s possible to answer this recent flare of racist action not with a bigger flare, but with a bucket brigade.

The road from Charlottesville will be rocky. There is no nationally funded community-based anti-racism campaign dedicated to convincing Nazis that they need to be reasonable…except the public library. This is our role, part of the reason that libraries are so critical to a functioning democracy. Halliday, director of a library that recently looked actual Nazis in the face, is ready. “Despite recent events, we still believe in the power of education and libraries,” he says. “We will not give up.”

Anna Call is a reference librarian at the Nevins Memorial Library in Methuen, Massachusetts. Follow her on Twitter @evil_librarian.

Anna Call