Discover Buck’s Pantry: “an engaging storyline . . . a witty and uplifting novel”—Kirkus Reviews

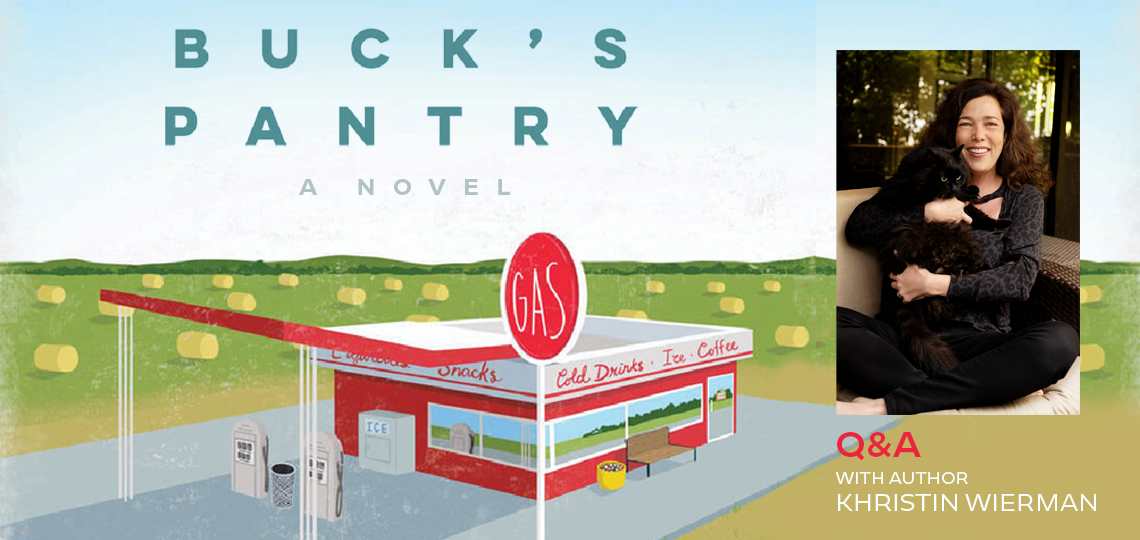

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Khristin Wierman, Author of Buck’s Pantry

Forget best or worst, a life-threatening crisis has a way of bringing out the essence of a person. Someone may behave in admirable or despicable ways when under intense pressure, but you can be sure that however they react is an authentic representation of their character.

Khristin Wierman’s interest as a writer of fiction is to use stress and the unexpected to reveal depth in her female protagonists. “There’s this sort of magical place in writing,” she says in the interview below, “when the characters begin to take on a life of their own and reveal depths you didn’t know were there. They begin to surprise you.”

When he discovered Khristin’s recently published novel Buck’s Pantry, Executive Editor Matt Sutherland made such a compelling argument that we had no choice but to assign him the task of interviewing Khristin. As you’ll see, his enthusiasm for the book is contagious.

Enjoy!

A random crime of the wrong-place, wrong-time variety sets up much of the compelling drama of Buck’s Pantry, demonstrating how life can change in seconds. So, what inspired this story?

A nap, actually. I woke up with this idea of two women, vastly in contradiction to each other, being trapped in a convenience store. Immediately, I knew I wanted it to be in Texas. And to use the Texas vs. East Coast culture clash in those two characters. Separately, I’d known for a while that I wanted to write a story containing a thread about mental illness, specifically from the point of view of someone experiencing it tangentially—not only having to watch someone they love suffer with it, but also having to live through the collateral fallout themselves. With those two “seeds,” I started writing some scenes, which is generally how I begin.

Early in the book, Lianna does a spectacular hit job on Gillian’s Republicanism, exposing Gillian’s blind devotion to a set of beliefs that are counter to how she really feels. Yet Gillian gives as good as she gets, often correcting Lianna’s mannerisms and salty language. They are women of different cultures and their relationship is very entertaining to observe. Did you enjoy bringing these two to life?

I had so much fun with these characters. There’s this sort of magical place in writing, when the characters begin to take on a life of their own and reveal depths you didn’t know were there. They begin to surprise you. I grew up in Texas in similar circumstances to Gillian. My professional life took me to the East Coast for many years. And there were so many low-stakes, surface differences to play with—Gillian’s colloquialisms and fussiness about manners; Lianna’s horrible language and missile-like directness. But what became apparent to me was that deep down Gillian and Lianna were similar in so many positive ways: both strong, both brave. They both have agency, and when the stakes get high enough, neither shies away from it.

The ending for me—for which I’ve been wrist-slapped a bit as it doesn’t follow traditional thriller or epilogue rules—was really the most special part of the book. Being able to show (I hope) that once they get past the surface conflict and the trauma, these women complement each other and have unique abilities to support each other. They make each other stronger, more balanced, more interesting. And there’s never any competition between them.

Aimee’s mother has always been terribly demanding, and not until Aimee discovers a handful of self-help books does she begin to understand how toxic the relationship is to her own wellbeing. But Aimee also feels responsible for her cousin Andy’s worsening mental health condition because she’s had less and less time to call and visit him as her life gets busy. When it comes to both her mother and Andy, the guilt she feels is quite oppressive. As it relates to Aimee’s role in the book, can you talk about this family dynamic?

Being the child of a wounded adult is tricky on so many levels. Not only is that adult your caretaker, but also your primary source of information about the world and your place in it. If a parent’s expectations are unrealistic, a child often doesn’t have any other data points. And it’s an invisible sort of poison—often nothing appears to be amiss on the surface.

Being the “healthy” person in a relationship with someone who is mentally unwell can be similarly crippling. It’s traumatizing to watch someone you love struggle and suffer. It’s traumatizing to be asked to fix things that are beyond your ability to fix. And there’s this especially weird place in between doctors (who have expertise that you do not) and the patient (who’s body and mind you do not inhabit) where you are expected to help figure out problems about which you have no direct information. As the “healthy” one, your needs will never trump those of the person who is sick. Your strength and energy are continually diverted into their situation—which can leave nothing for yourself.

In both cases, your sense of boundaries—of what’s your job to solve and what is not—becomes all out of whack. It feels wrong to take care of yourself instead of someone else. You carry blame and responsibility that isn’t yours to bear. And as you sink underneath those impossible expectations, it doesn’t feel like anything “should” be wrong.

My mother suffered from mental illness that went undiagnosed for many years, then took her in and out of hospitals. Both Aimee’s mom and Andy are drawn from my experience with her. Fiction is such a beautiful thing because it allows you to take feelings from real experiences and weave them into a story that you have the ability to direct, on your own terms—protecting the innocent (and sometimes not-so-innocent), adding levity to soften blows, creating happier endings for everyone.

Lianna and Aimee experience a few days of respite in the home of Gillian and her husband, Trip, and are mesmerized by scenes of domestic tranquility—rambunctious toddlers, a wolf-sized dog, bountiful meals, a beautifully appointed home. In fact, being cared for by Gillian is profoundly healing to them both because Gillian is so kind and loving. Why was it important to you to show Lianna and Aimee as two adult women in need of female caretaking?

Your question makes me smile because what was on my mind was showing some of the gifts Gillian and Trip have to offer. There is a hospitality in Texas, a particular kind of graciousness and neighborliness. And it’s so often lost in bigger ideological debates. I wanted to show this side of the place where I grew up. For me, this book became a love letter to Texas, although I know some critics don’t see it that way.

It was another sort of a magical moment when I could also show the healing effects that Gillian’s and Trip’s gifts—as small and surface level as they may seem—have on Aimee and Lianna. There’s a cost to being strong all the time, to always relying on yourself. And sometimes, it’s only small acts of compassion that can make it through the walls we put up to keep ourselves safe and strong. Or that can get past the barriers of what we think we deserve.

I feel like it’s so easy to lose sight of the impact of small kindnesses. To get sucked into the belief that unless you do something huge and world-changing, you’re not contributing at all. We need people to do big things. We also need people who can make smaller moments more bearable, more healing. Because when a thousand small moments coalesce and compound, I think they can create big improvements as well.

Trip and his father, Big Floyd, have a mostly dysfunctional relationship of their own, further complicated by the son working for his dad at a local bank. Meanwhile, Trip’s mother is a skilled meddler who constantly pushes buttons in Gillian and Trip’s marriage. As the novel progresses, the tables turn very satisfyingly, as Gillian and Trip learn to stand their ground, and Big Floyd lends them a hand. With such a strong cast of females, what was on your writer’s mind as you fleshed out the roles of the male characters in Buck’s Pantry?

The men were also so much fun to write. When I first began the book, I knew Gillian and Trip were fighting, but I didn’t know about what. As the shape of the story became clearer, Big Floyd emerged, who is based on my grandfather. And not in a loose way. The story about Big Floyd seeing a man’s arm coming through the window in the middle of the night and grabbing it to pull the burglar inside? That happened.

From those moments—I got to imagine Big Floyd really evolving, changing how he viewed the world, and becoming a stronger supporter of Gillian and Trip.

Please share a few details about your writing process, other writers who influenced you, and the types of stories that most appeal to you.

I want to read books that make me laugh, make me think, and leave me feeling better about the world, not worse. I want to read about characters who are wildly imperfect and still find ways to grow and succeed and change what they don’t like about themselves. At so many difficult moments in my life, reading stories in which circumstances improved was the only balm I could access—so happy(ish) endings are very important to me.

It’s such a gift when you’re reading a story and a phrase makes you laugh out loud. Or an author strings together a sentence that is like a key turning in a lock and opens up a whole new way to at least consider something you’ve never questioned before.

Augusten Burroughs’s books have meant a lot to me, many of which I was fortunate enough to find at a really dark time in my life. He’s a phenomenal writer—so funny, so adept at putting together smart, witty words and weaving them into a story you can’t put down. And he’s brave enough to write memoir, which leaves me in absolute awe. I’m also a huge fan of Taylor Jenkins Reid, Brit Bennett, Matt Haig, Jonathan Tropper, Janelle Brown, Kevin Wilson, Stephen Chbosky, Marcie Maxfield, Lianne Moriarty, and Laurie Gelman.

In terms of my writing process, it’s fairly fluid now. When I first started—after I’d left the corporate world—I was quite rigid in terms of a daily writing schedule and word count. Mostly because the idea of actually being able to do something I loved and enjoyed felt contradictory to everything that had been instilled in me growing up. It took a long time for me to let myself be more relaxed about it.

I think it’s different for every writer and what matters is finding your own rhythm—what makes you feel good and the effort feel worthwhile. For some people, fixed structures are a wonderful support. For some of us, they feel confining. There’s no right or wrong answer, just what works for you. And that can change over time.

Where will you next direct your writing talent?

Thank you for asking! My next novel is in the final stages of editing. It’s a different story, but also one that is close to my heart—about a woman rethinking her successful corporate career in the hopes of finding a way to make it more fulfilling. There are so many bumps and am-I-losing-my-mind moments that often come along when you decide to try and take your life in a new direction, and that’s what drew me to this idea. It’s called This Time Could Be Different and is on the SparkPress roster for September 2023. If anyone is interested in finding out more about me or my books, my website is: khristinwierman.com and I’m on Instagram at @khristinwierman.

Matt Sutherland