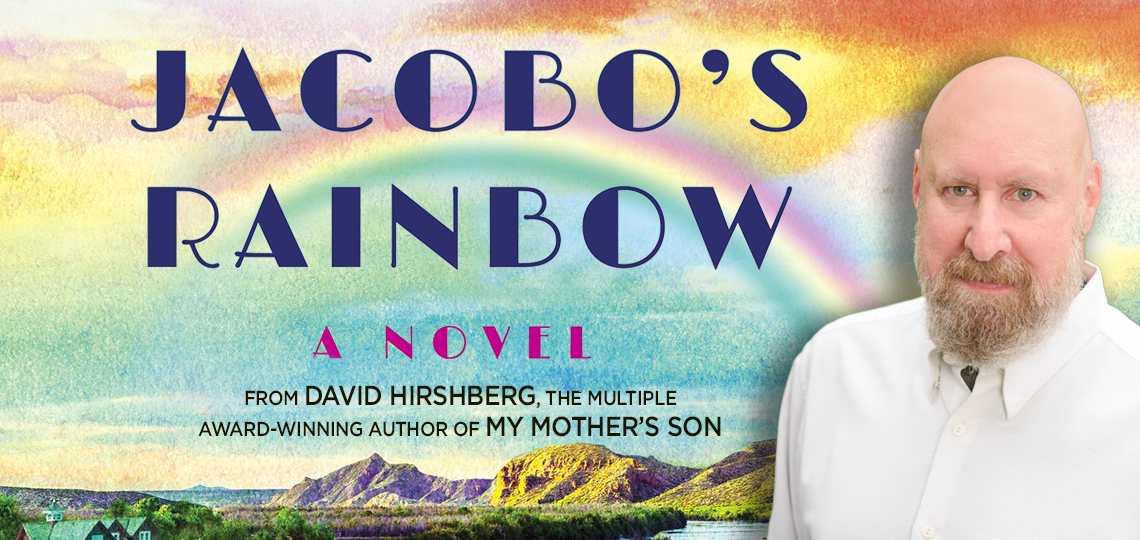

Editor-in-Chief Matt Sutherland Interviews Award-Winning Author David Hirshberg About His New Novel, Jacobo’s Rainbow

Setting aside the Great Depression of the 1930s, there are two unforgettable decades that stand out in American consciousness over the past one hundred years: the Roaring twenties and the sixties—and if you’re left wondering what all the hubbub is about, you can’t do better than to check out some of the great books based on those periods: The Great Gatsby, say, or The Sun Also Rises; and for the sixties, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, Helter-Skelter, and Slaughterhouse Five would be a nice start.

In Jacobo’s Rainbow, David Hirshberg is making a bid to join the short list of very special novels about the tumultuous sixties—a time of reckoning as the US finally began to confront systemic racism, poverty, its aggressive use of military force, and other societal ills. Today’s headlines betray a country still engaged in that reckoning fifty-plus years later.

Foreword’s Matt Sutherland recently caught up with David for the following conversation.

Jacobo hails from a hidden, Shangri La-like enclave along the Rio Grande in remote New Mexico, a place that hasn’t appeared on any map since his ancestors settled there in 1677, nearly three hundred years ago. So, as he heads off to the University of Taos (which doesn’t exist) in the early 1960s, he has some cultural catching up to do. Jacobo’s time-travel innocence is delightful to watch as the issues of the day unfold. Talk about how you created and developed these plot ideas? Is there historical precedence to a place like Arroyo Grande?

There is no historical precedence to a place such as Arroyo Grande; it’s the uniqueness of the village that’s central to the story. There were, of course, many settlers who went north from Mexico in the 17th century, and some may have lived near each other. But a Brigadoon-like village doesn’t exist to my knowledge.

When I started to think about how best to bring the events of “the Sixties” to life, it occurred to me that the vantage point of a naïf would allow me the most freedom to explore the plusses and minuses that we’ve taken from these turbulent times. I certainly wasn’t going to use a trope such as a Forrest Gump-like character or someone who’s come out of a coma and awakens to find things drastically changed. I needed something original that was also believable. I ended up writing much more about Arroyo Grande than what appears in the book, as I needed to determine if readers would suspend disbelief of this fictitious place to see it as real. Once I created a whole village and a significant number of people that looked to be plausible, I then cut it back to its essential elements, as I didn’t want the weight of the story to be on the village as opposed to on the campus, on the river, or in Vietnam.

The campus protest movement Jacobo joins in Taos encompasses a potpourri of issues: civil rights and voting registration in the southern US, the Vietnam War, and local flashpoints like racial hiring and housing discrimination. War, representation, racial strife, poverty—these protest topics have been around for millennia What’s also interesting about the 1960s, is that the campus battles were, in the main, mostly fought by middle class white kids. What is it about this time period that so interests you, and do you think there are things about the protest movements that get overlooked or are not well understood?

Many people look back today on the twenty years after the end of World War II as a kind of golden time when the economy rebounded, the Interstate Highway System was developed, and America got its space program untracked. The GI bill helped returning vets buy homes, college attendance increased significantly, the Salk polio vaccine was heralded in a new era of scientific achievement, and a young senator was elected president.

And yet … Jim Crow was alive and well holding down Black voters, systemic racism prevented minorities from getting mortgages and buying homes in white areas, extreme poverty was the norm in many sections of the country, indigenous Americans were practically invisible to whites, politics became a blood sport (viz. McCarthyism), and American forces were deployed in land wars in Korea and Vietnam, while Americans at home were disconnected from these conflicts. Discrimination was an accepted (although unacknowledged) norm in college admissions and employment, and, at the same time, the American Dream could only be imagined, for the most part, by an elite group of whites.

Looking back on this era now, it’s much easier to see the fault lines between opposing forces, and this is what I wanted to tackle—in literary fiction, holding up a mirror so that Americans of the early 21st century could get another view of “the Sixties.” In addition to tackling the Free Speech movement and its legacy today, I wanted to bring campus anti-Semitism—which was then just emerging out of the shadows of the 1950s—to the front and center as a mirror for what’s going on nowadays in a much more virulent form. I wanted to challenge readers without hitting them over the head with simplistic set ups and denouements. It also allowed me to write about the Vietnam War, which so traumatized the country at that time—and its reverberations haven’t ceased to this day.

Clearly, a lot was overlooked at the time of the protest movements. There wasn’t much subtlety about positions that people took. It was as if those times were a precursor to the digital age in that you were represented as a one or a zero, but there was no room for someplace in between. Subtlety was not a hallmark of that era.

I also think that what wasn’t understood was that people on both sides of the barricades were completely convinced of the righteousness of their positions. Compromise was not part of anyone’s lexicon. That’s why we’ve never learned the lessons from that decade. Unpopular positions may have gone quiet for a while, but they didn’t disappear. So the student rebels who thought that they won have found out that maybe they didn’t. And this is a lesson for all those today in favor of cancel culture. They may shout the most, intimidate the opposition, but who knows how this will play out in a couple of generations from now.

Ben Veniste plays an instrumental role in Jacobo’s understanding of the politics and powers-that-be that shape the ways government leadership maintains control, including Ben’s familiarity with the dirtiest of tricks. He’s also a longtime friend of Jacobo’s father and is familiar with the secrets of Arroyo Grande, as well as more than a few secrets about subterranean Taos. Please talk about the crucial role Ben plays in the book?

In the beginning, Ben Veniste was a minor character. He was just the owner of a restaurant where Jacobo and his friends hung out. As I started to develop him, he took on a life of his own (yes, this happens to writers!) and after a short time on one of my rewrites, I knew that he was going to play a major role. He becomes a surrogate father figure for Jacobo, his best friend, Herzl, and his girlfriend, Mir. But more than that, he’s a representation of a family of immigrants who settled in the US and didn’t shed their history, culture, or way of life. So while outwardly he assimilated from a business point of view, he kept his independence and sense of obligation to help others in dire straits. And he does this without intruding into Jacobo’s life as a threat to Jacobo’s family. More than one person who read the manuscript has told me that they identify with Ben Veniste.

Throughout the book, Jacobo’s inner dialogue shows an innocent becoming more and more savvy in the ways of the larger world, as well as a very prescient observer, mystic, and philosopher, coming into his own. And his Vietnam War experience certainly matured him all the more. In a sense, he is a perfect posterboy for the 1960s. How did this fascinating protagonist arrive in your imagination? And did he come to you in full, or did he lead you on a journey as the book evolved?

Wow, that’s a terrific set of questions. In truth, none of the characters (major or minor) in any of my novels has been fleshed out right at the start. In Jacobo’s Rainbow, I wanted to have a character who could see multiple points of view, so not having him grow up in a traditional American home—with all the readers’ preconceived notions—enabled me to start with a tabula rasa and build from there. And, importantly, as he went on his journey, he changed along with the circumstances. Without giving anything away, readers will get to see a Jacobo near the end of the book who is interviewed on television by a famous host (disguised) who’s quite different from the Jacobo at the start of the book.

Might there be a prequel to Jacobo’s Rainbow in the works? It certainly seems like you could have some fun exploring the lives and journeys of the ancestors of the Arroyo Grande before they ended up in New Mexico. Can you talk about what you’re currently working on?

A prequel for Jacobo? Not likely!

I’m in the final throes of A Bronx Cheer, another literary novel that’s set primarily in the 1950s in The Bronx and Upper Manhattan. It’s a modern retelling of the Jacob and Esau story from Genesis. The narrative that propels the story forward concerns the destruction of a neighborhood in the guise of progress. Jay and Eric, the sons of Ike (an Italian Jew), and Rebekeh, (a Mountain Jew), are estranged—as are their parents—and find themselves on opposite sides of a bitter struggle that pits those in power against the defenseless people of a local community. It’s a real New York story and the first one in which I use what I euphemistically call “street language.” It’s gritty, fast-paced, and cinematic.

With regard to what might come after that, I have some ideas kicking around, but until I come up with an opening sentence or paragraph, I can’t move forward. I knew when I wrote, “When you’re a kid, they don’t always tell you the truth,” that I could start my debut novel, My Mother’s Son.

Jacobo’s Rainbow was a vague idea until I wrote, “It seems as if anniversaries have a way of letting spirits loose, and they don’t respect boundaries any more than viruses do, so the only way to fool yourself into thinking you can control them is to make others believe that they can see them as well. A conjurer uses sleights-of-hand, feints, and misdirections, which can succeed because you’re willing to suspend visual disbelief. However, an author only has one dimension to work with, as well as a disconnected audience, which can be a disadvantage. But on the other hand, there’s no one to say that what you’re reading is false. Today marks the fifteenth anniversary of a momentous event in my life—the day I was sent to jail. It’s the obvious time for me now to tell my story. My guess is that you’re going to believe this is fiction; that would be a delusion.”

I’m telling the reader that it’s a novel, but I’m also saying that it’s a delusion if one thinks it’s fiction. That may appear to be oxymoronic, but I’m trying to separate the actual fictional events from what could happen in real life. And to top it off, this prologue isn’t signed by David Hirshberg, but by the protagonist, Jacobo Toledano. I’m deliberately creating some mystery. As in My Mother’s Son, I want the reader not to automatically assume that what’s being read first is necessarily the truth. Reading the book is a process of discovery that should be enlightening as it unfolds.

Matt Sutherland