Editor-in-Chief Matt Sutherland Interviews Steven Heighton, Author of Reaching Mithymna

As our planet continues to warm, historical weather patterns will change and many regions will be thrown into turmoil because of drought, flooding, variations in ocean currents, and other unforeseen effects. Consequently, in the years to come, tens of millions of people will be forced to leave their homes to seek refuge wherever they can. They won’t have a choice—and most of them won’t be welcomed with open arms in neighboring countries, many of which can barely support their own citizens.

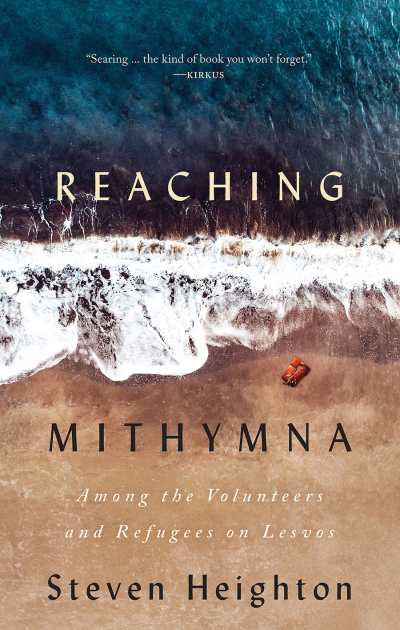

This week’s book project puts a spotlight on the Syrians who escaped a brutal civil war in North Africa and offers some typical, albeit horrifying details about the refugee experience. Did you realize, for example, that many women take contraceptives before they begin their journey knowing of the high probability of being raped? Or, how about the local fishermen in the waters near where the refugee boats arrive? In Reaching Mithymna, Steve Heighton tells us that many of those fishermen can’t sell their catch because of the possibility that those fish may have fed on the bodies of drowned refugees. These are not the type of insights you get in a brief Associated Press article, and they’re exactly why it’s important writers like Steve cross oceans, facing great personal danger, to cover an important story.

In her review of Reaching Mithymna for the November/December issue of Foreword Reviews, Susan Waggoner writes that the book conveys “the sense of an endless tide of desperate immigrants” and “leaves searing impressions of the Syrian refugee crisis with its unembroidered facts and experiences.”

Our editor-in-chief, Matt Sutherland, looked to Steve’s experiences as an irresistible opportunity to learn more about refugees and volunteers alike. With the help of Biblioasis, we set up this conversation.

Matt, take it from here.

First of all, I wholeheartedly commend you for your volunteer work in Greece. It was an awesome thing you did.

Every volunteer, I assume, has their moment of no return, when they finally talk themselves through all the doubts, and attend to the necessary details, before catching a plane and, exhausted, arrive for duty. What drove you to the decision to volunteer as an aid worker in Greece and was it a difficult one?

I made the decision overnight. This is unusual for me. Normally I ruminate, agonize. Often I run out the clock and do nothing. My default explanation for this quick, clear decision is that I’d been reading about the crisis and the need for volunteers on Lesvos; I figured my slight knowledge of Greek, my mother’s first language, might make me more useful; I was between drafts of a novel featuring imaginary Mediterranean refugees, and in light of the real-life catastrophe there, my fictional project seemed trivial. It also helped that flights were dirt cheap because of the crisis’s effect on tourism.

All those points are valid. But in the end, a vivid, disturbing dream decided me. (Don’t worry, I won’t describe it.) I went to bed thinking, “You should go to Lesvos but you probably won’t.” I woke up knowing I was on my way. It was the first time in my life a decision was dictated by a dream—by the nightmind vividly asserting itself, delivering a verdict. I was prepared to pay attention, though, because for several years before that, my poetry had been coming mainly in the form of verbal dreams … As I once wrote, “It might seem paradoxical that sleep should play such a vital role in awakenings of a spiritual kind. But it’s during sleep that the nightmind, like a drug-inspired auteur, screens footage that ranges from mere nonsense to intense little Symbolist films that confide crucial insights and leave us thoughtful, touched, and troubled. For the first time in my life I feel lucky to be a light sleeper—a recollector of dreams. Sleep now is a cavern I crawl into in hopes of illuminating encounters, poetic or personal.”

From doctors and cooks to translators and supply coordinators, along with others to perform the more humble tasks of serving, cleaning, and crowd control duties, volunteers fill lots of roles in a camp. Did you arrive with skills or an expectation of how you might help? What about most of the others you worked with: did the camps run smoothly or did it lean chaotic because so many were unqualified to do the jobs they were asked to do?

I figured my flimsy knowledge of Greek might prove useful. Nope. Arabic translators were what was needed (the only one in Mithymna hadn’t slept in weeks), so I and the other volunteers had to make do with whatever simple Arabic we could pick up. Paramedics were needed—and though I was forced into a paramedical role in an emergency a few nights in, I am no paramedic. We needed personnel familiar with the island, to lead groups of newly-arrived refugees to bus rendezvous. Instead, volunteers like me had to follow lousy directions in the dark while pretending—so as not to alarm the exhausted refugees—that we knew where we were going. We needed infrastructure so that we wouldn’t have to resort to Bronze Age technologies like the beach- and cliff-bonfires we built out of discarded life vests to guide the rafts in. I dramatize these and other issues in the book. I say that Lesvos was like one of those war zones you read about, where the turnover rate is so high that raw recruits are promoted in days. So you have rookies leading rookies. The result, inevitably, is chaos. But there were saving graces: the volunteers were hard-working and good-hearted, and the refugees were patient, determined, and seemingly fearless.

In the early days of your time in Mithymna, your feelings for the people you were helping confuse you. You write: “Our efforts can make us feel not more connected to the people we’re trying to help but more separate. Like patrons, not partners in the mission. You have to fight the tendency. You have to remind the ego (always keen to regard itself as special, always afraid of dissolution into the Many) that physical bodies all belong to one state without borders: the democracy of the dying animal. You can’t help wishing someone would remind you of it every time you wake up for the rest of your life.” Can you talk about how these emotions evolved, the longer you stayed and spent more time with the refugees? And your feelings now?

The feeling deepened by the day, and now, five years later, I feel the same; I still wish some spiritual drill-sergeant would sound reveille each morning, then forcefully remind my ego of its ultimate insignificance.

Here’s a related (I think) paradox I’ve been pondering: the same amazing facility of habituation that allows refugees to survive long internments in a stalag like Camp Moria also causes people in safe, privileged situations to habituate to their security, so they stop noticing it and feeling grateful. We’re all moral amnesiacs. I slept poorly last night (disturbing dreams again) and today I’m inclined to whine about my fatigue instead of focusing on gratitude and remembering what I saw and learned on Lesvos.

Please give us a sense of the desperate scene in Syria during 2015? What were the refugees escaping from? What were they seeking in Europe, by way of Turkey and Greece? What type of people are the Syrians?

I doubt I could generalize even if I knew—and because of the language barrier I know little. What I could see is that the refugees varied from wealthy (a few) to middle class (some) to poor (many). What they had in common was that they were fleeing a civil war in their country, they were arriving with no possessions, and they were risking their lives to seek asylum and a new life somewhere, mainly northern Europe.

With tens of thousands of refugees arriving on her shores, Greece, ill-equipped financially, suffered enormous strain as a nation trying to deal with the crisis, in addition to managing the more than seventy NGOs working on Lesvos alone. But what about the everyday Greek people, in your experience? How did they handle the crisis? Were they hospitable? Indifferent? Antagonistic?

The Greek traditions of philoxenia and philotimo—roughly, generosity-to-strangers and pride-in-doing-good—go back to the time of Homer and beyond. So I was not surprised by the kindness or at least tolerance of most of the Greeks I met. But even in 2015 I could sense a disgruntlement growing among some of the local folk—and who can blame them? Not only was the Greek economy in woeful shape but on Lesvos the refugee crisis had destroyed tourism, the island’s mainstay. Many businesses had closed over the summer and fall of 2015. Many more would close the following year. Would North Americans, under similar circumstances, keep accommodating migrants? How about your town, my town?

You’ve asked me for an answer but I’m concluding with questions, tough ones.

What’s next for you? How will the Mithymna experience influence your future writing?

Although I’ve considered how that experience has affected me on a personal/political level, I haven’t thought about how it might have influenced my writing. Now—thanks for the question—I think I see the answer. That month made me less reliant on the intellect as a moral guide and more trusting of the heart and the subconscious—of dreams, like the decisive one I mention above. The great John Prine, whom we lost to the pandemic in April, sang, “The heart gets bored with the mind and it changes you.” Amen. My latest project is an album of songs called The Devil’s Share, and I suspect my turn towards song owes a lot to what I saw on Lesvos and how the refugees and the other volunteers inspired me.

Matt Sutherland