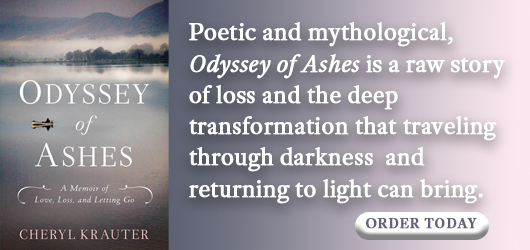

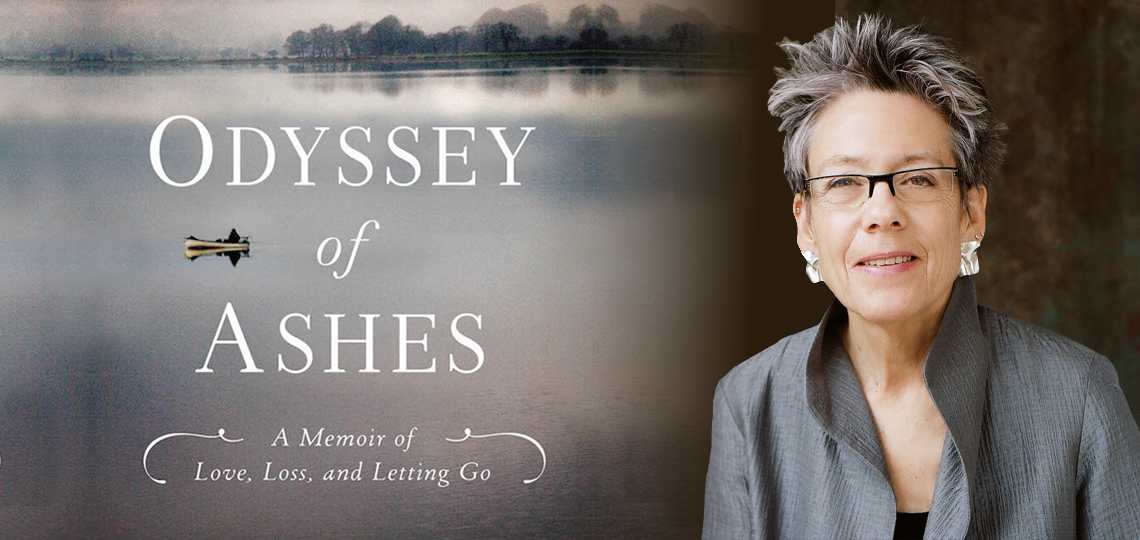

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Cheryl Krauter, Author of Odyssey of Ashes: A Memory of Love, Loss, and Letting Go

After the death of a loved one, the five stages of grief predictably leap into action but they are far from the only emotions that come into play. In fact, every grief experience is unique and experts confirm that there is no right or wrong way to mourn.

One of the most absorbing accounts of the grieving process we’ve seen is Cheryl Krauter’s Odyssey of Ashes: A Memory of Love, Loss, and Letting Go—detailing the heartrending death of her husband, John, from a sudden heart attack, and the initial years of her recovery.

A psychotherapist for several decades, Cheryl brings the highest level of introspection to this memoir. Her vulnerabilities and strengths, intellect and courage, are on full display.

Knowing that grief is integral to the human experience, we asked Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland to connect with Cheryl for the following conversation.

Fly fishing meant a great deal to both you and John, and also helped in your recovery from breast cancer through an organization called Casting for Recovery. But time on rivers and streams for you was often highlighted by simply being still, mesmerized by your surroundings. Can you talk about your love for this artful pastime, what it meant to you and John as a couple, and its place in your life today?

I found peace being on rivers. Standing in water, surrounded by the green and golden hued brush that lined the water, glimpsing a view of the occasional redtail hawk gliding far above me, a light breeze rustling through the trees, brought me a sense of calm that was eons away from the intensity of my daily life. I am grateful to John for showing me this connection with the natural world, a bond with the environment that I would have not discovered on my own as fly fishing was not on my radar. These were often quiet times for us, moments of simply being together. However, our fishing excursions did not start out peacefully as, during our early outings, John would try to guide and teach me and this, to put it mildly, did not go well. We learned to hire a guide for me and when we would go together on our own, we fished without the risk of an argumentative tutorial. We found our rhythm.

Joining John in the experience of fly fishing was also a way for me to become closer to him by being interested and learning about something that was a passion for him. I think that when we stretch ourselves into new territories and explore something we wouldn’t have considered ourselves, it is a gift we give to one another in an intimate relationship. We open our hearts to what matters to our loved ones and this, I deeply believe, creates a true union between us.

I have not fished since that trip to Montana because it felt too painful to do it without John. I just couldn’t imagine it. Yet, today, five years since that odyssey, I feel more ready and even drawn to fly fishing, hiring a favorite guide, floating along on a beautiful river, wading into a stream. I imagine the fun that my friend Bill and I could have fishing together. I no longer feel undone by the thought of casting a line and looking for “fishy water.” We’ll see how this evolves.

One of my fondest memories of fishing with John is of us, after a day of fishing, finding a log to sit on and sharing a sandwich while looking over a stream or river. That lunch was more delicious and special than any meal at a Michelin Star restaurant. I’d give anything to have that lunch again …

Scattering John’s ashes along his beloved Madison River in Montana proved to be quite the odyssey, as the title of your book suggests, punctuated by a ultra rare viewing of the aurora borealis later that night. At times heartbreaking in your despair, and also with lighter, even comical, moments, how do you now look back on those few days? Did they deliver what you hoped?

I made the trip to the Madison River in Montana without any preconceived notion of what might happen on my journey. The only thing I knew was that I was taking John’s ashes to scatter by a river that he had dreamed of but never got the chance to fish before his death. How could I have possibly imagined the chaos and turbulent hours of the storm I would find myself in on that day in July of 2017? The images in my mind’s eye, the sounds and the smells, the cold storm that turned into heat, a night sky lighting up with the aurora borealis, are kinesthetic memories I carry in my body. I knew it was an odyssey but in no way could I have had any idea of what would happen and how it would happen—in that way, I remain in awe of the magnitude of an adventure that I could never have predicted or planned.

I believe I captured the odyssey as I lived it. Taken over by nature, I was blown along in a storm, I was caught in the unceasing current of a mighty river. I was carried by a force beyond my understanding, I was traveling in a flow that demanded that I follow and not fight against. I did not create the experience, the experience awaited me and I lived it. I will remember this day as one of the most powerful of my life … one that could never have been scripted in my wildest dreams.

I think about the spot on the bank where I scattered John’s ashes during the storm. It is especially poignant in winter when I know the ground is covered with snow and the river is freezing. It is in these moments when my heart hurts …

Explain how your ability to “suspend the rational mind” helps you with grief?

As a child, one of my favorite movies was The Time Machine, an old black-and-white portrayal of the novel by H.G. Wells. On early Saturday mornings while my parents still slept, I must have watched it dozens of times, fascinated in my own imaginary world. As kids we’d asked each other what we would wish for if we had only one wish. My constant request was for a time machine.

—Excerpt from Odyssey of Ashes: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Letting Go

My fascination with the mysteries of life and the magical thinking that I embraced as a child have always been an integral part of who I am. I strongly believe that it is a tremendous loss if we bury or let go of that part of ourselves in exchange for the rational, black and white thinking that is often expected of us as we grow into adulthood. Our educational system prizes the ability to give the “right answer” and society rewards those who “fit in” as an extension of this type of learning. I’m not negating the need for rationality which is clearly necessary for us to be responsible in our lives, however, the rational mind is intolerant of anything it cannot perceive or comprehend. This linear thinking cramps creativity and denies access to mysteries that are beyond our limited knowledge.

The mysteries of the universe intrigue me and I am drawn to all that is beyond my comprehension. The writings of mystics and poets awakened an inner world within me and have opened up the doors and windows of my consciousness. For over thirty five years, I have practiced Buddhist mediation and this path continues to be a touchstone in my exploration of presence. Presence is timeless, a place of peace and power, the kind of silence that allows me to connect deeply within myself. Being in the stillness of the moment allows a voice that speaks to the timelessness of grief and brings me to understand the bigger picture of myself, my life, my losses.

The rational mind might end the exploration of grief by putting a hard stop on the experience. As if to say, “that’s enough, it’s over, move on.” By now I think it’s crystal clear that I am not a black and white thinker, I’m not that concrete in the ways that I perceive others, the world around me, and that which is beyond my understanding. By suspending what some might define as reality, I hear John’s voice, feel him close, sense him in colors or light, and in dreams. This opens my heart to the eternal and infinite quality of grief.

You write about the expectation that loss gets easier with time, and that it isn’t true for you. “Grief has no finish line, no real conclusions.” Some will certainly take that as a terribly depressing thought. Please help us understand your reasoning?

I don’t believe we ever stop grieving the loss of someone we love. The experience of loss changes over time and by leaning into our grief rather than escaping into distraction or a kind of numb denial, we deepen as human beings and discover that the losses of our lives do not diminish us but give us a more expansive perspective than we may have believed possible.

I’ve been an Existential Humanistic psychotherapist for over forty years so my belief in the basic truths of human existence, that death and loss are inevitable aspects of being alive, is foundational in how I hold grief. I also work with people who have been diagnosed with cancer and other life-threatening illness along with their partners and family members and these relationships have given me a window into human suffering. It is a great honor to walk alongside these people and they have taught me profound lessons of grief and loss. There is often a push for people to “get over” their grief, to move on too quickly. There can be a pressure to find meaning in grief immediately rather than to allow the feelings of sorrow, anger, and fear to emerge organically. This can create feelings of guilt and shame and people can sink into believing that something is wrong with them. Sadness and grief are not the same as depression, which is actually the absence of feeling, a numb turning away from personal experience.

In my work with life-threatening illness and end of life care, I have talked with many people who feel comforted by the circular nature of grief. Far from being depressing, people have found solace and comfort in realizing that nothing is wrong with them, that they’re not flawed when grief knocks at the door in unexpected ways. Seeing grief as circular allows the experience to be less frightening and becomes an opportunity to connect within ourselves in continually deepening ways.

The horrific and senseless losses from gun violence brings the ongoing nature of grief into a stark and painful landscape in our hearts and minds. The loss of children, racially motivated hate crimes targeting innocent shoppers at a grocery store, a lunch at a church shattered by gun fire are all incidents that will not, should not, be forgotten. My hope would be that grief that is associated with senseless violence does reach a finish line and come to a conclusion.

There’s an emphasis on gratitude in Odyssey of Ashes, a message of traveling through darkness into light. I have felt this personally in the six years since John’s sudden death and have also received messages of how the book offered hope to those who have read it. I have heard that the book helped people to feel less alone, that they felt understood. One recent comment I received came from a someone who, after reading the book, felt that “my range of experience can be broader.” In the end, I believe that my story centers on healing and transformation. I hope that this is a takeaway for the readers of Odyssey of Ashes: A Memoir of Love, Loss, and Letting Go.

In an informative passage about the places where trout tend to hold in a river—in the margins between fast and slow water, for example— you write: “I have come to understand that I, too, live in the margins, roaming the edge between the deep and shallow water of my soul, becoming an underwater creature in the silent turbulence of my grief.” Please expand on this enigmatic thought? Do those margins sustain you just as they do a trout?

The margins in a river or stream are a place of rest for fish, a safe spot and a respite from predators, a pause from the energy it takes to navigate rushing waters. Margins are spots where creatures are hidden from view. When fish lie in the margins, they are getting a break from being in the current of a river or stream. I felt that I was living on the edge of deep grief while still swimming in the shallow waters of the responsibilities of my daily life, working, paying bills, grocery shopping, and interacting with others. The duality of being in both worlds felt surreal.

For me, living in the margins felt like a place to roam alone, to hold still, uninterrupted by the expectations and demands of a busy life. It was a break from the force of the current of my grief. I experienced my grief as watery and, at times, felt as though I was floating alone in bodies of water without any land in sight. To retreat into a spot along the bank of a stream where I could rest, feel protected and safe, felt sacred and calming. Like a solitary fish, I could let the water hold me until I was ready to swim back into the flow of the river.

You’re an avid, observant dreamer and the book is sprinkled with descriptions of some of your more evocative dreams. What beliefs do you have about the importance of dreams in your life?

I became interested in dreams during the early days of the human consciousness movement of the 1960’s when, at the age of seventeen, I was introduced to psychology and the study of dreams. I learned about the Senoi Tribe of Malaysia and how they used dreams for growth and change in their lives. It was fascinating and I loved that the lines between fantasy and reality were not viewed as always distinct and how that was seen as something that didn’t matter!

The research and study of this tribe and their dream experiences was later discredited, however, some of the theory is still very much alive in how dreams are explored today. An example of this is the suggestion to turn and face the creatures and characters in a nightmare, to introduce yourself to them in order to discover the messages and lessons that they are bringing to you, to recognize what part of you these shadowy, scary figures represent. The sharing of dreams with others has roots from the Senoi tradition of telling their dreams each morning to other members of the tribe.

I kept dream journals for decades and found that there were themes that would appear as familiar threads throughout my dreaming life. Sometimes a dream would bring me around to a theme that hadn’t shown up in years and this was often an undiscovered layer of my own psyche emerging. These recurrent images were reminders of what I might be engaging with in my waking life or they could be related to an inner part of myself that wanted to become conscious, to be known. I have had dreams that were not personal but more related to what is known as the collective unconscious. These dream experiences are defined by the theories of Carl Jung who believed that human beings are connected to each other and their ancestors through a shared set of experiences and that this collective consciousness can help us to understand the world and others in a way that travels beyond the limits of our personal understanding.

I believe that dreams are a window into the unconscious mind. Our dreams bring us an awareness of what we filter out in our waking hours and are therefore free of the controlled definitions we often invent to explain ourselves, others, and the world around us. I trust my dreams to bring me an awareness of who I am and show me the possibilities of what I am learning in my life. As Carl Jung wrote, “In each of us is another whom we do not know. He speaks to us in dreams and tells us how differently he sees us from the way we see ourselves.”

Year after year, you create a Día de los Muertos altar for those couple days of remembrance in November. While dismantling the offerings on the last night in 2018, you write, “The veil between the world of the living and the dead has closed and those of us still here are left behind as the dead fly away into an ethereal landscape of our imagining. We can’t know where they wander, we only know the dull ache of forever missing them.” Please expand on that connection to the dead, and other rituals which help your wellbeing?

Ancient and indigenous cultures created rituals to honor the dead and to allow for continued contact with those who have gone to the other side. In our modern, western culture, the fear of acknowledging and accepting death has led to a lack of ritual to honor those who are no longer with us in human form. When we create rituals or use those that are already established, we give ourselves moments to be with those who are no longer with us. These moments of remembrance can bring feelings of closeness and remind us that the person we knew, our experience of them, lives inside of us forever. They will always be a part of us and we feel connected to them through the ritual celebration of our relationship with them. We allow ourselves to feel how they’ve touched us and, in this way, we hold them within our hearts when we cannot hold them in our arms.

Your son, Ben, never took to fishing, a sore point for John because he was hopeful for idyllic family vacations on the nation’s great trout rivers. But in your roles as mother and wife, John’s insistence on dragging Ben to fish caused you genuine discomfort—even as both of them showed little sympathy for you as you strived to mediate. In fact, they seemed to resent you for not taking their respective sides and the relationship between them struggled for years. But they did reconcile. Please give us a sense of those painful years for you and how the making up with Ben affected John?

To be clear, the family relationships were not continually fraught with pain and though there were years of struggle between John and Ben, it wasn’t the whole story, it was a chapter not the entire book. Nor would I say that John insisted on dragging Ben to go fishing. Yes, he hoped that Ben would love to fish and kept trying to put together outings where that might occur. John was very thoughtful about choosing family friendly spots when he planned these fishing expeditions. Unfortunately, his own desire that Ben would enjoy fishing created a tension that affected us all. I feel that this speaks to how expectations of others can put pressure on ourselves and others and damage relationships. However, he stopped putting these trips together and had let go of that hope years before the two of them began a process of reconciliation.

I think it was in my role as wife where the most discomfort occurred for me. My concern for John’s woundedness was always present and he probably felt (as he was very perceptive and intuitive) that I, in many ways, felt more supportive of his son that I did of him in those incidents. I felt so caught between them at times! It is also important to know that John talked with me privately about his difficulties and would listen to my perspectives. He would always return to Ben and talk with him. Later Ben would often say to me, “I know you talked to Dad.” Indeed, this became a running joke between us. After John died, I had a conversation with Ben, asking if he had felt resentful and abandoned by me during these conflicts. He was genuinely surprised by the question and answered by saying that he had never felt abandoned and has always felt my love and support.

It was painful for me to watch the conflict between them because, as a psychotherapist, I felt that my ability to help others fell flat in my own family. I felt helpless and that is not an emotion that I am used to feeling. My own trauma of growing up with a critical mother was triggered and I felt a fear that didn’t really belong to the present situation in my family with John and Ben. I needed to own my discomfort as something that I was responsible for working through. As he was a kid, I didn’t expect Ben to take care of me or even understand—that was not his job. I would have liked John to have had some understanding of how their troubles felt to me but that never came to pass and that was disappointing to me. But, in the end, it was not my business to interfere in the relationship between father and son, it was not my fight and the realization of this was life-changing for me.

I hope that John felt some sense of healing between him and Ben before his death. I know he was trying very hard to repair their connection but I’m not sure if he was able to let go of his disappointment in himself and the strong inner critic he carried within. This is a conversation that I wish I could have with him today. It makes me sad to think of all that could have continued to heal if he had lived longer. It reminds me to live in the present and pay attention to the importance of nurturing my relationships, remembering to take nothing for granted.

What’s next for you and your talented pen?

Once I realized that writing didn’t mean that I’d always have to write another book, I’ve been writing smaller pieces for blogs, submitting pieces with prompts on certain subjects that are appealing to me, thinking about op-ed ideas. After spending the past nine years writing three books, it was a revelation to me that I didn’t always have to work on a large project!

Several people have suggested the possibility of writing a screenplay based on Odyssey of Ashes. I’m definitely interested in this idea and have laid some groundwork on this project.

I have written poetry since I was an adolescent and was editor of the literary magazine at my high school. One of my poems has been published and out of the volumes I have written throughout my life, I might have a couple of poems that are actually decent, good enough for publication. I was fortunate to study poetry with the Beat poet Diane di Prima and would be interested in finding another poetry teacher to guide me in the future. Putting together a book of poetry feels like a return to my writing roots—from adolescence to older age—note, not old age!

I’m interested in writing a novella and have an idea that’s marinating in me.

I’m thinking about writing something that speaks to how psychotherapists have joined the group of first responders during this era in the world: COVID, gun violence, war, social justice issues, climate change, and complex layers of distress are traumatic issues that those of us who work in health care are dealing with at this time. I believe we will be working with the intensity of these struggles and the need for emotional healing for years to come.

I do have a pretty wicked sense of humor, sometimes light, sometimes dark, so I’d like to write something funny. I keep thinking I might be able to write a “beach read” and imagine this book as a best seller, but I seem to be a voice for the unspeakable so I’m not sure that I’ll ever manage to write a popular book.

Matt Sutherland