Flannery O’Connor’s unpublished novel in print for the first time!

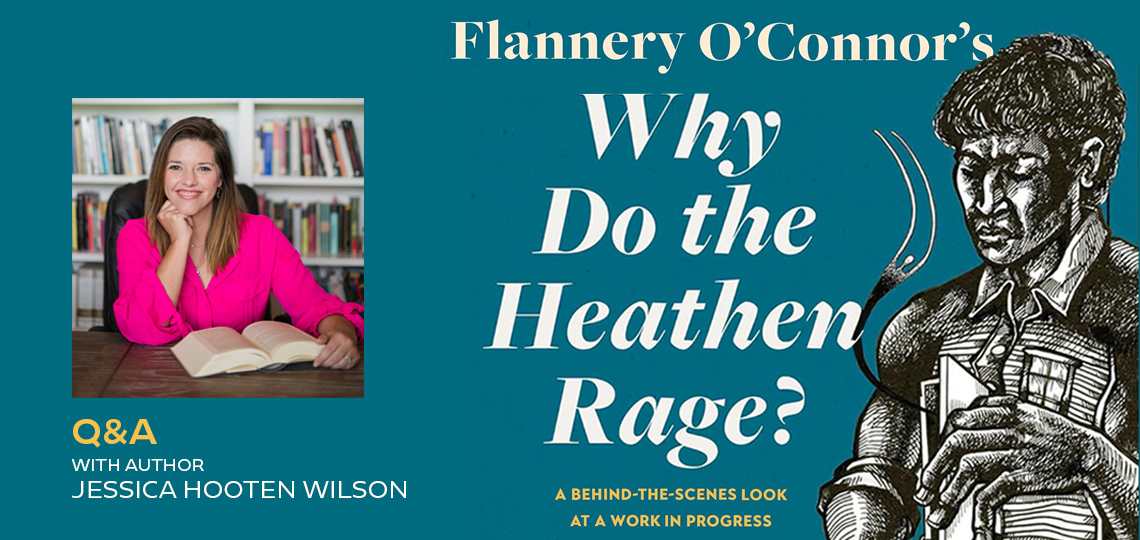

Editor-in-Chief Michelle Anne Schingler Interviews Jessica Hooten Wilson, Author of Why Do the Heathen Rage?: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress

A much-too-young legend was lost in August 1964 with the death of thirty-nine-year-old novelist and short story virtuoso Flannery O’Connor. Her brilliant work and reclusive life in rural Georgia—worlds away from literary circles—made her a fascinating figure and her passing left readers bereft.

She also left some unfinished work, including nearly four hundred pages of Why Do the Heathen Rage?, which confounded scholars but inspired today’s guest to spend ten years studying the draft to get a sense of Flannery’s aspirations for the novel.

Jessica Hooten Wilson’s Why Do the Heathen Rage?: A Behind-the-Scenes Look at a Work in Progress caught the Flannery-loving eye of Foreword’s Editor-in-Chief Michelle Schingler and we quickly set about getting the two together for a conversation.

You write that Flannery O’Connor approached characters unlike herself with Austenian caution, rather than with audacity, resulting in some writer’s block on the topic of integration and Black lives. When do you think such caution becomes detrimental to fiction writers and their work? How, if at all, do you think it might benefit their work?

An African American pastor dialogued with me regarding this caution in O’Connor’s work and challenged it. All people share enough common humanity to empathize with one another’s emotions, relate to one another’s experiences, and thus create art that illustrates various points of view not limited by the author’s gender, race, age, and so forth. However, I grow anxious when I hear that a white male author is writing a story in first person from a black woman’s perspective (I sat through a public reading where this happened) because there are also distinctives about each of our experiences that are difficult to step into fully. Artists should approach this task with as much humility as audacity.

You also express hope that Flannery would have reconciled herself to her discomfort enough to complete Why Do the Heathen Rage? in time. How long do you think she needed, and why?

Flannery took five years to complete her first novel and seven to finish her second; based on that limited pattern, she may not have finished this novel for almost a decade. A forty-year-old or fifty-year-old Flannery would have written a different novel than the thirty-something O’Connor began here. We are all in process in learning about one another and opening ourselves up to others’ stories. This novel shows further steps in O’Connor’s journey and hints at where she was going imaginatively.

If completed, how do you think Why Do the Heathen Rage? would have fit into her oeuvre?

I’d like to think that Why Do the Heathen Rage? would have been O’Connor’s best novel. She had more success crafting short stories. Her first novel was sewn together from her MFA thesis writing; her second novel structurally is repetitive. This novel was born in the seeds of another story that had more to show. The idea for the plot shows greater potential than the plotlines of the first two, with more room for character development, and even a possibility for romance, which has never been a strength in O’Connor’s work. She was writing a novel that would have not only spoken well to the current issues of her day but also to us decades in the future.

Having spent time with the innumerable fragments of Why Do the Heathen Rage?, what scenes stuck with you the most and why?

I laughed aloud the first time I read the scene where Walter sits on a rock near the mailbox and reads Oona’s recent response to his theologically erudite letter. He mutters, “Good God in hell.” I too have read nonsensical but passionate discourses from people about their experiences of the world and the silly things they believe and wanted to respond likewise. When Walter counts her exclamation points, I could hardly contain myself. That may have been the first time I thought, “People have to read this!”

Walter and Oona never meet in any of Flannery’s fragments. What do you imagine their meeting would have been like?

In the second version I made of these materials, I tied them together with my own insertions. I imagined Oona approaching Roosevelt on the porch to kiss him, thinking he was Walter, and Tilman stomping on her clogged foot with his cane. I saw Walter offering her to stay for dinner in mock heroics, and later giving her a tour of the place. Of course, I offer in this book a version of Walter’s conversion that I wrote, and it was meant to be a starting place to living like a holy fool. If I finished the novel, Oona would be the one chased, as she darted off to Koinonia with Walter on her heels, dancing like David before the altar.

You note that Flannery existed at quite a remove from the integration and civil rights movements of the 1960s: she spent her days on Andalusia in Milledgeville, Georgia, in an ailing state; she lived with her mother alone; and most of her communications with the outside world were (like Walter’s) via the post. Do you imagine that she would have been more involved with social justice movements had she not been dealing with lupus, or do you think that her reticence to participate ran deeper than her health issues?

O’Connor was hesitant to act on behalf of any cause. She saw her vocation as a novelist. Unlike her counterpart Walker Percy who was born into a family who felt compelled by civic duties, O’Connor was not raised to lead any charges. During her time in high school and college, O’Connor wrote humorous stories and poems and drew cartoons; she did not run for class officer or write editorials. She was a prophet, not an activist.

What do you wish that those who “canceled” Flannery after the Paul Elie piece (many of whom, you point out, were so unfamiliar with her in the first place that they didn’t even know she was a woman) knew about her and her work?

Flannery O’Connor transcended her time more than she was a product of it; she helped us progress from the limitations of our views on race, not to mention on faith. I’ve had students in tears reading “Everything Rises Must Converge” because it held up a mirror and showed them the racism of which they didn’t even realize they were guilty. I’m not interested in exonerating O’Connor of all sins because I do not need to do so in order to learn from her work. I assume writers are as sinful as I am; I have yet to read a writer who got everything right all the time. But what Flannery does get right in her fiction has shown me how to be a better person.

You were introduced to Flannery via a writing instructor who saw you struggling to reconcile the expectations of your Christian parents with your impulses toward art. Would you gift her to kindred aspiring writers for the same reasons now? Who else would you include among your recommendations, and why?

YES! I think all aspiring artists should read The Complete Works of Flannery O’Connor, including her essays and letters. I would also recommend Daniel Nayeri’s Everything Sad is Untrue, for ways of seeing how to experiment with storytelling and break the mold; Ann Lamott’s Bird by Bird for instruction; and Ambition, a collection of essays by the Chrysostom Society for encouragement.

How has Flannery’s work influenced your own work, both fiction and nonfiction?

When my first book came out—it was on Flannery O’Connor—the reviewer indicted the book because he couldn’t tell the difference between what she thought and I thought. Having loved Flannery’s work since I was fifteen, I fear I can hardly unthread her work from my way of seeing the world. I hope one day to write fiction the way that she mastered, but until then, I am gratified by lifting up her genius for the world’s enjoyment.

Michelle Anne Schingler