Four Native American creators weave together the story of Keepunumuk, the time of harvest

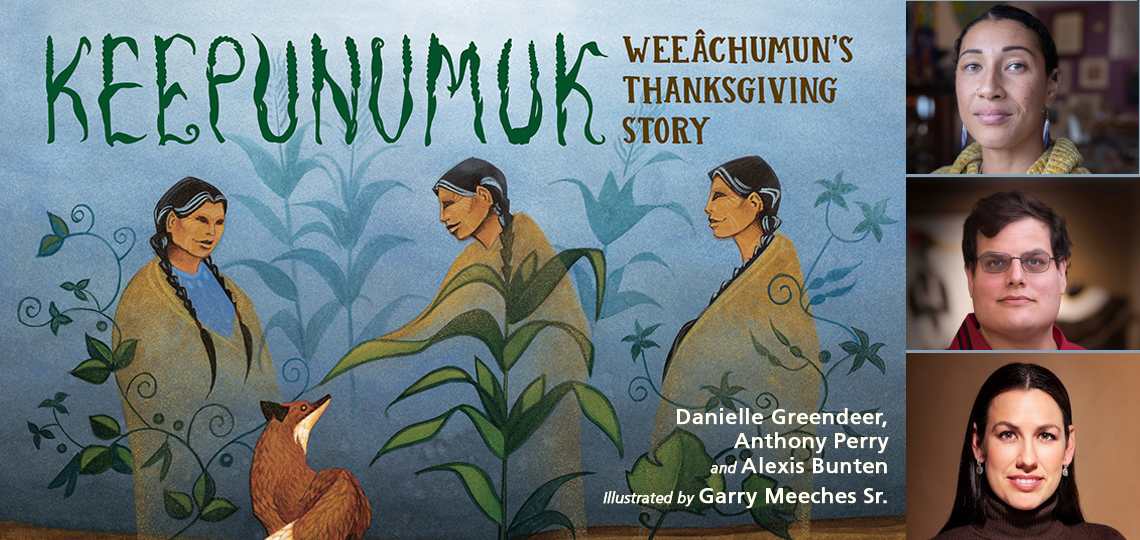

Reviewer Danielle Ballantyne Interviews Danielle Greendeer, Anthony Perry, and Alexis Bunten, Authors of Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story

When it comes to the Thanksgiving holiday, there’s a great deal of hyperbole clouding the simple truth that a tribe of Native Americans came to the rescue of an impoverished group of European immigrants nearly four hundred years ago. This act of kindness, of sharing locally-sourced food and the expertise needed to grow and gather it, is what makes the story transformative. Is there a better lesson to share with our children?

We’re excited to be joined by the Native American authors of a very special new picture book that puts America’s Indigenous people and nature back at the center of Thanksgiving—without the clichés and stereotypes. Keepunumuk: Weeâchumun’s Thanksgiving Story earned a stellar review from Managing Editor Danielle Ballantyne in Foreword’s July/August issue. We jumped at the chance to bring reviewer and authors together for the following conversation.

How did you all connect to coauthor this story?

The journey to write Keepunumuk began with a “Decolonized Thanksgiving” meal that Alexis organised in 2016 to educate Americans about the truth behind this holiday. The meal was well received and began with a campaign to “decolonize Thanksgiving” with meals that replaced the turkey and stuffing with indigenous foods such as venison, duck, and three sisters soup.

In 2018, Alexis interviewed Chris Newell, a Passamaquoddy activist who has long campaigned to decolonize Thanksgiving, on Facebook Live about the myths of the Thanksgiving story and what really happened. Tony, who had just published his children’s historical fiction book Chula the Fox, watched the interview and was amazed at how little he knew about the “First Thanksgiving.” Tony wrote Chula the Fox to bring his Chickasaw history to life and knew the powerful role stories can play in how people see the world.

Tony shared an idea with Alexis, whom he knew from university (both went to Dartmouth College): Why not create a new Thanksgiving story that replaces the narrative so many Americans grew up with? They decided to write a children’s picture book that tells the Thanksgiving story from a Native American perspective.

Though they were both Native American, neither is Wampanoag. They knew they needed to get free prior and informed consent from the Wampanoag tribes, because this is fundamentally a Wampanoag story. Alexis contacted her friend, Danielle, who is deeply involved in Wampanoag traditions and cultural revitalisation in her ancestral homeland to ask how best to approach this. Danielle responded with: “You know, I would like to write a children’s book.” Alexis and Tony then asked: “Would you like to write with us, and be our lead author?” Danielle said “Yes!” and Keepunumuk was born.

Why did you feel it was important to tell this side of the “Thanksgiving” story in the form of a children’s book?

Keepunumuk isn’t just about telling a new Thanksgiving story. Keepunumuk is about creating a new national narrative that puts Native peoples—and Nature—at its heart. Our goal in writing this book was to create a story that becomes the first exposure to Thanksgiving for the youngest of readers, and to replace stereotypes with empathy for all peoples and the interconnectedness of nature. As Keepunumuk becomes childrens’ default narrative, their parents’ taken for granted assumptions become challenged and change over time.

It’s important to remember that the Thanksgiving story so many Americans grew up with was itself created in the 19th century. Sarah Josepha Hale, an editor and publisher, campaigned for decades for a “national day of thanks.” She wrote President Lincoln in 1863—at the height of the Civil War—with her petition, and he agreed. This gave rise to a new American story, centered around the bravery of the Pilgrims who risked their lives to create a new life. The Thanksgiving story lies at the heart of the American ideals of freedom and opportunity, but those ideals came at the expense of the Native peoples whose lands the Pilgrims—and other European settlers—occupied.

America again faces fundamental questions over its identity and future. It’s time for a new narrative for its birth, rooted in history and centered around the Native peoples, and Nature, that made it possible.

Being that you are all Indigenous yourselves, how did you each approach and balance writing a story of the first Thanksgiving with your acute awareness of the harm that followed—and continues to follow?

This was one of the greatest challenges that we faced, especially writing a picture book for the youngest of readers. The “First Thanksgiving” did not end well for Native peoples. The Pilgrims returned their thanks fifty years later by killing the son of the leader who saved them. This wasn’t new. Since the first European traders arrived on the North American continent, Europeans and, later, Americans regularly attacked and exploited Native peoples. Native peoples lost their homelands and their children were forcibly sent off to boarding schools designed to destroy their cultures, languages, and lifeways. Native Americans today bear the scars of their ancestors as they fight to save their languages, cultures, and identities for their future generations.

We struggled to strike the right balance between telling the truth and upsetting our readers. While we definitely wanted to replace negative stereotypes about Native peoples and share the truth of what happened to them, we also didn’t want to vilify the Pilgrims. It would have been easy not to focus on the meal, making no mention the price Native Americans paid to make it possible. However, doing so lets the harm stand, making it harder to reconcile and heal. We can’t transform the Thanksgiving story—and the American story—without recognising this harm.

In the end, we took a two-part approach. On one hand, we note in the story that many Native peoples see Thanksgiving as a day of mourning. This leaves the reader wondering why. To this end, we added more information in the back matter, noting that many Wampanoag people died because of the warfare and disease introduced by European settlers. We hope this leads to further exploration and conversations as young readers grow older that recognise the challenges Native peoples face and the triumph of our survival today.

What do each of you hope is one key thing children take away from the story?

We all hope that children learn the importance of gratitude and the challenges of compassion. We want children to relate to the natural world, and pay more attention to the plants and animals that we depend on, and that depend upon us.

We want anyone who reads this story to see that First Nations (and Native American) people are still here. We are vibrant and cultural people. Through the book’s imagery and storytelling, it shows that our language and our histories have persevered from first contact to today. It shows that our children learn from our elders and carry forward those lessons to pass down to future generations, ensuring our continued survival.

Are any of you working on anything currently you can share a little bit about?

We all are! Alexis has written a forthcoming picture book celebrating the first Native American secretary of the interior. What Your Ribbon Skirt Means to Me: Deb Haaland’s Historic White House Inauguration will be published by Little, Brown and Company in 2023. Tony’s working on the sequel to his historical fiction book Chula the Fox. Danielle is working on an Indigenous cookbook for children. Garry is starting some new projects with his nation in Manitoba.

KEEPUNUMUK

WEEÂCHUMUN’S THANKSGIVING STORY

Danielle Greendeer, Anthony Perry, Alexis Bunten, Gary Meeches Sr. (Illustrator)

Charlesbridge (August 2, 2022), Hardcover, $16.99 (32pp)

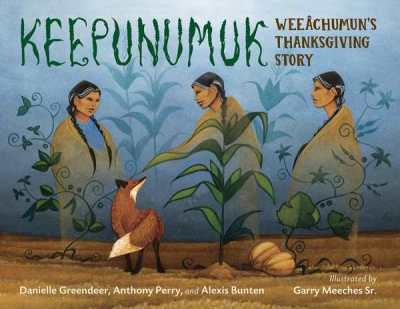

Wispy, dreamlike illustrations complement this tale of the first Thanksgiving from a Wampanoag perspective. Weeâchumun, the wise corn, and her sisters, Beans and Squash, are considered the three sisters of the harvest. When Weeâchumun sees the settlers arrive, she tasks Fox to watch them through the winter. When spring returns, Fox reports the newcomers are hungry and struggling, and the sisters send the First Peoples to their aid, setting history into motion.

Reviewed by Danielle Ballantyne

July / August 2022

Danielle Ballantyne