FTW BEST OF 2024: JULY–DECEMBER

This week we’re offering you a batch of our favorite questions and answers from the previous year’s fifty-plus interviews involving the reviewers and authors of notable new books covered in the pages of Foreword Reviews. Please set aside a minute or two—we know you’ll find a few nuggets of wisdom to help make your 2025 a year of much deserved health and happiness.

Reviewer Eileen Gonzalez Interviews Sidney Morrison, Author of Frederick Douglass: A Novel

Douglass had a complex relationship with those who enslaved him. While he was unequivocally antislavery, he was willing to meet and even reconcile with those who had horribly mistreated him and his family. What do you think it says about Frederick Douglass as a person that he was willing to offer and accept olive branches in this way?

Frederick Douglass admitted he was an angry youth and adult, and I believe he had a right to be angry, given how he was exploited, abused, and mistreated. He also witnessed almost unimaginable cruelty, but he refused to allow his anger to destroy him. It became righteous anger, focusing his will, driving his ambition.

But Douglass realized the insufficiency of righteous anger. It could not heal his soul, or the soul of the nation. Only empathy, forgiveness, and reconciliation could do this, and after the Civil War he reached out to his enslavers despite severe criticism because he understood that slavery, bigotry, and white supremacy damaged everyone. Imperfect, he still desired to be a model, the representative man who challenged himself to do what needed to be done, “to bind the nation’s wounds,” as Lincoln had urged, in a personal way. This was not easy, especially when his enslavers were, as I believe, family. But Douglass was willing to acknowledge his debts to them, how they had contributed to his intellectual development, and even saved his life.

As a biracial man, he also believed he represented the future unity of racial America. There is a nobility of purpose, an expansion of the heart and mind that make him a great rather than mean, tribal, petty, and vindictive man. He could have been the latter, but he chose “the better angel” of his nature. He demonstrated the redemptive power of choice.

Talking to Kat Brown about No One Talks about This Stuff: Twenty-Stories of Almost Parenthood

Rebecca Foster: I was fascinated by the concept of disenfranchised grief—hidden grief that doesn’t get acknowledged by society. Is the situation getting better? (Thinking of things like free commemorative photography of stillborn babies, and urns or caskets for miscarriages.)

So much of this stuff is out there if you look, but in the moment—what is there really? What do we know instinctively to reach for? In her book All the Living and the Dead, my friend Hayley Campbell wrote some breathtaking portraits of bereavement midwives who help deliver stillborn babies. I would have had no idea they existed otherwise because I hadn’t needed their help.

Social media and changing attitudes mean that we can now talk and hear about what isn’t considered “nice” and gather support from friends and family that simply wasn’t possible years ago. Pain needs to be recognised in order for you to set it free. In the UK, the government has recently introduced baby loss certificates for anyone who has gone through a miscarriage. It’s thanks to the campaigning work of Zoe Clark-Coates, who has also introduced free and secular goodbye ceremonies in beautiful British churches for anyone who has lost a baby—even if they didn’t have the chance to conceive. This sort of inclusion and thoughtfulness is absolutely wonderful. I’ve been to one of the services with my husband, in a stunning Oxford cathedral, and it was really meaningful.

Reviewer Isabella Zhou Interviews Ella McLeod, Author of Rapunzella, or Don’t Touch My Hair: A Love Letter to Black Women

Black women’s hair is central in Rapunzella. It is the source of the witches’ power in Xaymaca and representative of their collective resilience, history, and culture. The narrator’s own struggles with coming-of-age as a young black woman are embodied, in part, by her decision to straighten her hair, a decision that is interrogated by her friends in Xaymaca. What would you say to Black girls who are themselves currently going through adolescence and struggling with self image in a world saturated with white, European beauty standards? What is the significance of these themes in a politically and culturally charged contemporary moment that is still often hostile to black women and their bodies?

Firstly—you are beautiful. Secondly—you are so much more than beautiful and your worth is not related to your desirability. The fact that you feel this way is not your fault. There is a wider context here, a long, racist, colonial history and a capitalist agenda that benefits from you feeling inferior. Ultimately, your journey into self-confidence is not one I can take for you and is one I am still going on. But for me, reading widely on this subject was intricately linked to healing. A Raisin in The Sun, by Lorraine Hansberry, Queenie, by Candice Carty Williams, anything by bell hooks or Maya Angelou … Realising that many black women had been where I was before me and had found a way through was heartening. It’s not so much about deciding to straighten your hair or not straighten your hair, as much as it is finding choice empowering not oppressive. There is no right or wrong answer but I do believe it to be important that we keep asking ourselves questions about why we’ve decided to wear something or say something. What do we assume about ourselves every day? Can we give ourselves the grace of making a decision for ourselves without being constantly preoccupied by the perception of others?

So much of my personal unpicking of the damage done by racist beauty standards was tied to gaining a broader understanding of liberation politics, which I suppose answers the second part of this question. At the moment, whether looking at the horrifying statistics around the world that show how black women are still so vulnerable to violence, or discussing the right of trans people to gender-affirming care or the ongoing battle around Roe vs Wade, the fight for bodily autonomy wages on. Women, and black women in particular, are disproportionately affected by this. Yes, our hair and the denigration of our hair is important, but hair here is also a stand in for a wider conversation about what we are entitled to and what the structures of capitalism and patriarchy, as well as the legacy of colonialism, strip from us. I really wanted to sew the seeds of these questions in the minds of young people.

Meet the Larger-than-Life Komail Aijazuddin, Author of Manboobs: A Memoir of Musicals, Visa, Hope, and Cake

Reviewer Kristine Morris: The title of your book relates to a certain physical characteristic, gynecomastia (enlargement of breast tissue in males), that together with body dysmorphia and obesity (the result of a tendency to seek comfort in food) caused you a lot of emotional distress throughout your growing up years. What might you now say to other young men dealing with serious body-image issues?

The short answer is structured jackets, but the longer answer is to be radically kind to yourself. You’re in charge of how you feel about your body, no one else. Not parents, spouses, friends, lovers, or strangers. When your brain tells you to be insecure about your nose or love handles or thighs or even manboobs, please remember that everyone (even that one fitness instructor on Instagram whose closest adult relationship appears to be with a box of prescription strength laxatives) is insecure about something.

The best way I know to combat those intrusive thoughts is to remember that self-acceptance is not a destination—it doesn’t magically materialize after reaching your goal weight or getting visible abs or running a marathon or finding a mate. It comes from repeatedly reminding yourself, hundreds of times a day if necessary, that the cruel voice in your head telling you are not good enough as you are is just that—a voice. It is not a fact—it is not the truth. What is a fact is that happiness comes from accepting yourself—first as you are now, and then walking towards what you hope you could be.

Reviewer Michele Sharpe Interviews Chris La Tray, Author of Becoming Little Shell: A Landless Indian’s Journey Home

Do you think reciprocity is an important part of culture?

It is the key to how we lived on this world for thousands and thousands and thousands of years, and as soon as we abandoned it, that is when things started to go sour in a very short amount of time, if you consider the length of time that people have been on the planet.

Reciprocity is everything. It’s recognition that everything we need comes from the earth and we need to act accordingly, in reciprocal relationship with the earth, to make sure we give back so that Earth can continue to provide for us.

Reviewer Interviews Papyrologist Roberta Mazza, Author of Stolen Fragments: Black Markets, Bad Faith, and the Illicit Trade in Ancient Artefacts

Reviewer Nick Gardner: By the end of Stolen Fragments, I think it’s obvious that you have a passion for the artefacts you work with and a reverence for their writers. That passion bleeds through to the point where I found myself wrapt while reading your book, a book about subjects I never imagined I would be interested in. I’d love to know what’s next for you? Another book? What kind of research?

I will go back to some basic papyrology—there are some papyri that are waiting to be published! But I am also playing with the idea of writing a book about “reparations.” There is a lot of noise about restitutions and repatriations, but I do believe that justice cannot be restored simply by giving back the objects. Reparations is a far more complex concept and endeavour, which should involve a collaboration between the perpetrators and those who have suffered not only from the loss of the artefacts, but also from the loss of the enjoyment of those artefacts. By taking control over the colonised production of knowledge and culture, colonial regimes have suppressed the possibility of alternative narratives, histories, and papyrologies, too—we tend to focus on what we have achieved, but the loss we created in the making is immense. We practise papyrology following a Western tradition rooted in the colonial imperial period, but I don’t think this is the best future path. There is a need to rethink and reshape papyrology like many other disciplines to make them more meaningful, more ethical: in short, far more interesting.

Reviewer Rachel Jagareski Interviews B.A. Van Sise, Author of On the National Language: The Poetry of America’s Endangered Tongues

You write that while there is good work being done to revitalize endangered tongues, this work is being done “in an America that struggles to reckon with its haunted past and its nebulous tomorrow, a confused nation at the crossroads of a pivotal moment.” Are you hopeful that some of the most endangered North American languages featured in this book will find new speakers and grow in the future?

I’m really optimistic, actually, but with an asterisk: it’s hard to define a language as dying in our modern era since a lot of folks are pulling languages out of the soil that haven’t been heard for a very long time. And so, there are folks here trying to save their languages from the brink of silence that … it’s the real world, they might not succeed. But their colleagues are exemplifying what Bruce Springsteen sang about years ago: maybe everything that dies someday comes back. I’ve seen too many people—especially young people—with such tremendous enthusiasm, that it’d be difficult to be anything but hopeful.

Reviewer Kristen Rabe Interviews Josh Davis, Author of A Little Queer Natural History

You note that, historically, queer behavior in nature was often explained away or described as abhorrent or immoral. Can you cite a few examples here? Are attitudes changing in the scientific community?

One of my favourite examples of how queer behaviour has been explained away is within dolphins. Both males and females engage in plenty of gay behaviours, including inserting various body parts (fins, flippers, noses, and penises) into the others’ urogenital slit. When some scientists observed these behaviours, rather than accepting that some animals engage in gay sex (and presumably enjoy it), they thought that it showed “proof” that sexual intercourse was divorced from sexual intentions. These scientists claimed, instead, that the animals were greeting each other or engaging in social behaviour.

Biased human perspectives can subtly influence how animal behaviours are reported. But these biases can manifest in more extreme ways when queer behaviours are covered up entirely. For instance, when researchers observed gay sex among Adélie penguins in 1912, the section on these behaviours was excised from the official account of the expedition. It wouldn’t be until a century later that it was discovered how this behaviour had been observed but then actively redacted.

Attitudes have definitely been changing, with more and more reports of these behaviours being published. While homosexual behaviours in animals are still underreported, this may reflect more about the way journals work rather than researchers’ worries about publishing this information.

But there is still often a subtle bias in language when describing non-heteronormative behaviours even today. For example, for fish species in which males may present as either males or females, almost invariably the female-presenting individuals are described as displaying the “alternative” mating strategy and “stealing” fertilisations, even if those individuals make up more of the population. The implication is that the male-presenting males are the “normal” ones who are somehow “owed” the right to mate, even if that is a value judgement we’ve put onto them.

Reviewer Jeana Jorgensen Interviews Elizabeth Lowham, Author of Casters and Crowns

Grief and memory are major themes of the book, with Baron haunted by his father’s death and Aria keeping meticulous records of her mistakes and flaws. How do you think their paths to healing are similar, or might offer useful takeaways to readers struggling with related issues?

Both Aria and Baron have to learn to forgive themselves, and that’s a hard lesson for any of us. Sometimes we carry guilt for things that are not our fault, which can be a misguided struggle for control over the uncontrollable. Can we forgive ourselves for not being able to control aspects of our own lives?

Sometimes we do things that are absolutely our fault, and it matters what we do in the wake of those true mistakes. Do we try to bury them or shift the blame? Do we punish ourselves and never move forward? Or do we take responsibility, make whatever amends we can, and try to become stronger so that we don’t repeat the error? There’s a big difference between taking healthy responsibility versus drowning ourselves in guilt.

My hope for myself and readers would be exactly what Baron says: “We all get it wrong, so perhaps the answer is simply mercy. Mercy for others, and mercy for ourselves. Besides that, walking forward is an ongoing path that doesn’t end at a mistake. There’s time to mend what can be mended, to improve at the next opportunity. You’re strong enough for that.”

Reviewer Danielle Ballantyne Interviews Jessica Friedmann, Author of Twenty-Two Impressions: Notes from the Major Arcana

Tarot and many other aspects of occultism have been growing in popularity but are still deeply misunderstood. What would you say is the most common misconception you encounter about tarot?

I was having drinks with a friend the other night and met someone who had been raised in an Evangelical household who grew up believing, and being told, that tarot cards were a tool of the Devil. And I think a lot of people still feel as though alternate or ancestral practices aren’t compatible with religious belief. But charms, amulets, incantations, and divination coexisted with religion in Europe well into the Middle Ages. There doesn’t need to be tension between them.

Divination, to me, is an interpretive practice. I don’t believe that you can predict the future with tarot cards, or with any other system, but I do believe that you can make yourself very still and practice a kind of active looking and listening that allows for the symbols of the tarot to emerge in a kind of organic meaning-pattern, one that helps make sense of unspoken or unidentified perceptions.

Reviewer Rebecca Foster Interviews Jessica Kirkness, Author of The House with All the Lights On

You describe sign language (Auslan, in particular) as being cinematographic in nature and reflecting people’s individual styles. I was interested to learn that as I think most assume that a signed language would be formulaic. Can you tell us a little more about how language and personality interact?

The beauty of sign language—like most languages—depends on the user. Just like in spoken English, there are some people who are gifted communicators or highly eloquent, and others for whom language is just a utility. Much in the way that hearing people have unique voices or patterns of intonation, Deaf people have their own signing styles. I suppose it’s a bit like a visual accent.

Both of my grandparents were very theatrical in the ways they communicated, even when they used spoken language. I’m a competent signer, but my grandparents were rich storytellers, and it was a joy to see them create images I’d never be able to replicate with my hands.

I think it’s a really common assumption that sign languages are formulaic, but that couldn’t be further from the truth. I’m always marveling at how clever sign language poetry and storytelling can be—how much individual and cultural choice can inflect the meaning made. There are subtleties and nuances that outsiders to the language might not be privy to, but the more you learn, the harder you realize it is!

Sign language is a rich and complex language that has suffered from hearing prejudices and assumptions over the years. It’s a language that has been banned, denigrated, considered animalistic and primitive, and that misconception has caused enormous harm. Since Covid, I think people are paying much more attention to sign language. Having interpreters on our screens for all those years has shifted something in our cultural landscape for the better, and hopefully many more people will consider learning the language and experiencing it for themselves.

Reviewer Peter Dabbene Interviews Yazan Al-Saadi, Author of Lebanon Is Burning and Other Dispatches

With authoritarian governments on the rise internationally, is the Arab Spring movement just a faded memory, or do you think it’s made a lasting impact? Which Middle Eastern countries have fared best, and worst, in the years since? Which countries do you think have the best chance of advancing individual freedoms in the near future, as opposed to regressing under threats of imprisonment and death?

I think social movements are living processes and their impacts, small or large, are felt over time. History isn’t a series of isolated incidents, rather it is a chain of contexts linking up to form the present and set the foundations of our future. The uprisings in the region more than a decade ago were not spontaneous events but were building over time for a variety of complex and simple reasons. Those core drivers (social, political, economic) have not been dealt with—meaning, we will inevitably have further uprisings arising in time.

Currently, none of the countries in my region have achieved the fullest forms of collective/individual freedoms that the communities living in them absolutely deserve (the counter-revolution, it must be stressed, was backed by regional and international powers, including so-called “Western” states).

I also hold the view that the struggle for self-determination in the region is part and parcel of a larger global struggle for self-determination. In my opinion, you, in the United States, are not free (you just think you are), and your struggle for the rights you absolutely deserve is also my struggle (and vice versa, my struggle is your struggle). We are all part of this fight for liberty and dignity because we ALL deserve better, and we have a lot to do in that regard.

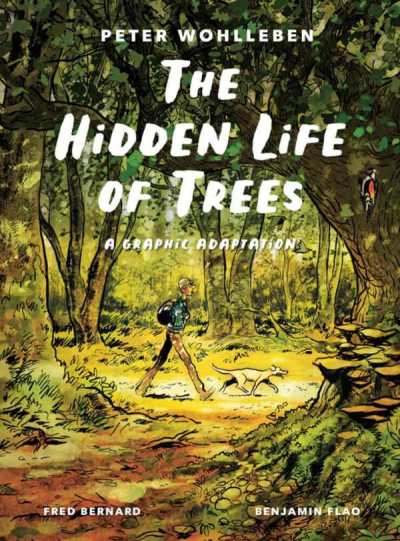

Reviewer Peter Dabbene Interviews Peter Wohlleben, Author of The Hidden Life of Trees: A Graphic Adaptation

The Hidden Life of Trees is an incredible book—thank you for giving the reading public this graphic novel version! One of the things that’s absolutely striking about it is the revelation that trees have an extensive network of partners they communicate with, like myecelium. Is this as recent of a discovery as it seems, despite the fact that humans have lived with trees for milennia? How did we not know about this earlier?

The fact that trees communicate has been known since the 1970s. Even earlier, in 1880, Charles Darwin described in his penultimate book that there is a plant brain located in the tips of the roots. Modern research confirms this, as does underground communication, some of which is actually carried out via the fungal network (the wood-wide-web, discovered in the 1990s). Plants have long been regarded as automatically functioning biorobots and have therefore hardly been researched, hence the surprise that they can do as much as animals, just differently.

Your efforts to promote environmentally sound forestry are admirable. Do you think more countries will adopt such policies in the future, or will short term incentives push back such initiatives? Can you share any recent success stories?

I am firmly convinced that we will achieve positive changes. Think of the Montreal Agreement of December 2022, in which the countries of the world promised to protect 30 percent of the ocean and 30 percent of the land by 2030. Sure, it won’t work everywhere so quickly, but the path has been taken. In addition, the new “Socio-ecological Forest Management” course at Eberswalde University of Applied Sciences, which I initiated, started in September—the first of its kind in the world. So forestry will also change. Even Jane Goodall visited me at the end of October to see the university and talk to the first students.

Matt Sutherland