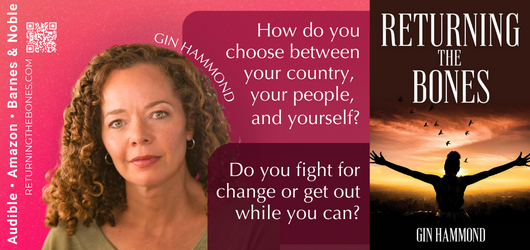

How do you choose between your country, your people, and yourself?

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Gin Hammond, Author of Returning the Bones

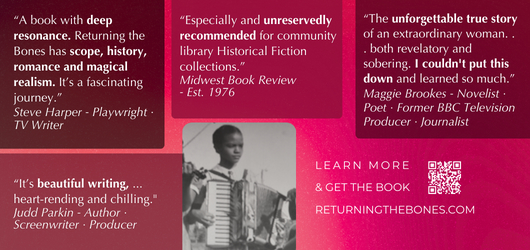

Great books leave their mark in unforgettable scenes and ideas. And a few offer more than seems possible.

In Gin Hammond’s Returning the Bones, we find ourselves alongside a brilliant young Black woman kneeling in bone-filled trenches at Auschwitz shortly after the end of World War II, in the midst of realizing that the Holocaust was real. That she was raised in a racist west Texas, earned a prestigious competition to study medicine in Europe, danced alongside Ella Fitzgerald in Parisien jazz clubs, and proceeded to take over her father’s medical practice back in Texas—all while hiding the ability to communicate with all manner of supportive spirits and apparitions—helps propel this historical novel into one of our favorites of recent years.

Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland earned the enviable assignment of catching up with Gin to discuss the bones of this extraordinary book, how it came to be, her connection to the characters, and so much more.

Enjoy!

I can’t remember the last time I read such a wide-ranging novel with as much depth and substance as Returning the Bones. It taught me a great deal about the pre-Civil Rights era, Black experience, post-WWII Paris, and even how the Holocaust rose out of the fog of hearsay—all through the eyes of a larger-than-life Black woman. Please introduce readers to the real—we learn in your prologue—Carolyn Beatrice Hammond (Bebe), and how this astonishing story came to be published.

It’s tempting to simply enumerate her accolades. Instead, I’ll start with the word I think describes her best: welcoming. To be welcomed was exactly what I needed when I started my journey with this story, because I was looking for family.

You see, my grandfather, who was born around 1890, was one of the first Black physicians in the state of Texas. My father was the youngest of his seven children, and I was the youngest of my father’s four. My relatives’ stories were so close and yet so far, and I knew far too few of them.

I took a leap of faith when I was in my twenties, and decided to find a relative, any relative, who could help me discover and understand my roots. Mind you, this was happening in the era when phone books were giving way to flip phones, so starting a casual conversation via text was not an option. Understandably, no one I contacted seemed interested in connecting with someone claiming to be a relative out of the blue. Each cold call was laced with suspicion on their part, and a good deal of “flop sweat” on mine. The ordeal made me feel like a bit of an imposter, and I was ready to give up, until I heard my Aunt Carolyn’s voice. What came next changed my life.

I flew out to Shaker Heights, Ohio, where she was living at the time. The moment I saw her, there was a lump in my throat. She looked so much like a cute, female version of my dad. In fact, she looked like me, give or take 45 years, save the contrast of our skin tones. I hoped and needed to somehow be accepted by her.

I was raised to be cripplingly polite, in a Black southern kind of way, so the first day or so was spent saying yes and no ma’ams and thank yous, and of course doling out compliments wherever I could spot an opportunity. A few days in, she allowed me to look through family albums. I discovered quite a few newspaper articles and awards jammed messily into binders and boxes. I asked her about them. Though Auntie Bebe accommodated my questions, she was exceedingly humble so it was a painstaking process.

Eventually the stories emerged, and I found myself blurting things like: “Wait, so you hosted Eleanore Roosevelt when you were student body president of Howard University? And what was it again that Lyndon B. Johnson said to you?”

Jumping ahead ten or so years, I wrote a well-received play about her coming-of-age. Audiences wanted to know even more about her, so I obliged.

As a child, Bebe’s imagination knows no bounds. She’s a bit paranoid, superstitious, hears voices, has invisible friends, takes grief and advice from statues and paintings as well as goats. Please tell us about some of the enigmatic, powerful women she descended from (mother, aunt, and grandmothers), as well as your decision to have her speak directly to readers, as if in a letter or a diary?

Getting to know these women has been one of the best things about writing Returning the Bones. Bebe’s mother is tough but so loving. Alongside her husband, she helps run a multigenerational household, a hospital, the domestic science department at the local college, and is a kind of diplomatic envoy to the rest of the town, not to mention a respected psychic. I didn’t want the character of Mother to be an archetypal drudge, however, so I delighted in creating scenes where men were falling over themselves to curry favor with her. Bebe finds each of these moments utterly mortifying.

Bebe’s aunt was a crusading librarian who was not afraid to take on the establishment, and who dedicated her life to uplifting her community through literature. To this day, there is a Prudence Curry Society operating out of the library she ran for fifty years. The story about Great Aunt Prudence facing down bulldozers is true!

Bebe’s Grandmother Sarah was heroic in her tenderness and faith despite having been born a slave. More than anyone, it’s Grandmother Sarah who instills Bebe’s belief in herself, even as a very young person. We all need a Grandmother Sarah.

One of the trickier characters is Great Aunt Ella, who “passes” for white. Returning the Bones hints at a torrid affair she may have been having with the local white sheriff. Circumstances of their day did not allow them to confess their ardor publicly, which spurred them toward a decision that affected everyone in town.

As for Bebe’s imagination, yes! It is unpredictable, often ridiculous, and causes Bebe no end of perturbation. I have many reasons for layering this into her character. The character of Grandmother Sarah, a Cherokee medicine woman, swats Bebe in the gut with a spray of herbs and tells her, “‘The more you listen there … the fewer problems you have here,’ she finished, adding another swat, this time on top of my head. ‘Even so, where would our people be if we had no imagination?’”

As for the point of view, I enjoyed the idea of the reader being a kind of confidant to Bebe as she tries to hold it together whilst navigating her outer and inner worlds.

Bebe’s father, a wealthy physician, defiantly builds a hospital and school for Blacks in response to the whites-only hospitals and schools in Bryan, Texas, in the 1920s. He’s also very active in registering his fellow Black citizens to vote. But his activism has the devastating consequence of instigating the Ku Klux Klan, including the murder a rural farmer, Otis Montgomery, who was pursuing an education. In a tense early scene, Mrs. Montgomery lets the doctor know he’s partially responsible for the death of her husband. Can you talk about this double-edged sword of activism, through Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era?

Defiant is the perfect word for Bebe’s father, Dr. Hammond, and he was well-equipped for it. He graduated from one of the ninety or so Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) that had been established during Reconstruction. By the time he was a student, however, Rutherford B. Hayes’ reprehensible Compromise of 1877 had dismantled most of the achievements of Reconstruction and fomented the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. This post-Reconstruction era, in which hard-won rights were systematically disassembled, is disconcertingly easy to relate to today.

Certainly, Dr. Hammond had no illusions about what he was up against, but he strove to break down barriers while lifting up as many people as possible along the way. The fact that he was a learned Black man, let alone an activist, was threatening to the white supremacists of his town. On one hand, because he was a high-profile target, I have gotten the impression that he may have received death threats more frequently than his Black neighbors. On the other hand, he had leverage in the form of medical records on white patients who would visit him in the middle of the night seeking treatment for conditions they wanted hidden from their white neighbors. His Black neighbors had no such protection. He was in a position to create positive change and he did so to the best of his ability; however, that left the most vulnerable in his community open to collateral damage. Whenever I ponder whether there may have been a “right” way to do things, where societal change could be created at no cost to those involved, I am at a loss.

Please talk about what must certainly be many years of research for this richly detailed, historically precise, and utterly mesmerizing peek into the lives of Black Americans in the early twentieth century?

In the tenth year of interviewing my Auntie Bebe, I brought a videographer with me on my next trip out to see her. The result was approximately ten hours of footage yielding troves of new discoveries that left me with even more questions. I spent hours in museums and libraries of all sorts, all over the country, hunting down answers. The Montgomery’s shack with its newspaper wallpaper, for example, is modeled after a shack at the Institute of Texan Cultures. I hit the jackpot when I was lucky enough to live in the Netherlands with my family for a year, which helped me research and construct details for the European scenes. I especially loved learning about the rich history of American Black expat artists in Paris. That’s where ideas for including details such as the white chalky boulevards of Paris and the loquacious lacquered lion in the nightclub door, were born.

Bebe is paralyzed by the guilt she feels for her brother’s death—believing that she killed him because soon after he saved her from drowning, he caught pneumonia and died. After the tragic death, Bebe is expected to step into the role of helping her father’s medical practice, and taking over when the time comes instead of her deceased older brother. But she flatly doesn’t want to be a doctor, which doesn’t seem to matter to anyone but her. Even through many years of medical school she is adamant she won’t be a doctor. But then she wins a prestigious competition and ships off to Europe in the summer of 1948 for nine weeks touring and study. World War II is so recent, she is stunned by the bomb damage, poverty, rationing, and ignorance regarding the Holocaust.

Even so, Bebe is thrilled to realize Count Basie, Ella Fitzgerald, Josephine Baker, and many, many other famous Black musicians and artists find Paris to be a much more friendly place than the States after the war. In fact, the colorblindness of Paris culture is intoxicating and Bebe is tempted to turn her back on marriage, a medical career, and even her family. Can you talk specifically about this very special place and time for Black Americans?

Black musicians and artists started migrating to Paris as early as World War I, and for the exact same reasons, they expatriated to France after World War II. For many African American soldiers, French culture offered insight into what life out from under the spectre of Jim Crow could look like. Naturally, many of these soldiers were reluctant to return stateside. Later, after Josephine Baker became one of the biggest stars of the 1920’s—so much so that legions of white European women were trying to emulate Baker’s hairstyle (!)—jazz gained a firm foothold in Paris. Parisiens’ love of jazz, a quintessentially African-American artform, and their egalitarian celebration of the American allied forces, lifted a veil from the eyes of many American Blacks who were bone tired of being treated as less than human back “home.” Since there was such and appetite in Paris for the fruits of the Harlem Renaissance, Black artists were lauded as heroes as much as the soldiers were, and this played out again after WWII.

In Hungary, a cafe owner tells Bebe that the concentration camps are the “worst rumor of the war.” But she works under a Hungarian doctor who speaks of the nameless orphans arriving from camps and ghettoes across Eastern Europe: “‘Wherever they come from,’ she said, pointing to the map with her cigarette, ‘the orphans … they keep coming. Three years later, they keep coming still. Many not knowing their family names. … The war doesn’t stop when governments say they do’.”

Along with some Jewish American friends, Bebe takes a train to Auschwitz to see for herself. They are met by a woman named Violetta who has committed her life to preserving the camp in the exact state left by the Nazis: the barracks and ovens, trenches filled with bones. I quote at length from this scene because it is so powerful:

“And it is a horror, especially to our trained eyes. We know exactly what we are seeing, down to the tiniest bone. I feel Violetta’s urgent hand at the center of my back. ‘You go in,’ she instructs. ‘You touch them. You take bones back to your own country.’ She glances toward the office near the entrance. ‘I bring sack.’ Her pale, fierce eyes transfix mine. ‘The Nazis … they studied the Jim Crow laws of your country. This is what they did with that information. Did you know?’ I drop to my knees at the edge of the trench. ‘You tell. You show your people. Go!’ she calls over her shoulder as she hurries toward the office.

“I place my hand lightly on the bones closest to me, closing my fingers around the left hand of a small skeleton. I coach myself to breathe steadily and think clinically, as I would if I were assisting with an autopsy—these are simply the phalanges, the distal, middle, proximal, which are connected to the metacarpals—but a sensation like a slow electric shock runs up my arm and throughout my body, and the light under this lifeless sky seems to shift. Something in this web of bones has been activated through my touch, and I kneel helplessly as it awakens.

Voices. So many languages, yet I understand them all. The urge to protect them, to take them someplace safer, holier, prevents me from letting go. ‘Miss.’ When I’m able to unclench my hand, I realize that Violetta is holding my heaving shoulders. There is a small burlap sack by my side. ‘Miss, these are not your people. Why do you cry?’ She asks this like a professor reviewing something obvious and fundamental. ‘Because I am a woman …’ I squeeze the words from my throat as my ribs shudder of their own accord. ‘I am a daughter, a granddaughter …’

With each identification, my hands lead me back to different sets of bones. Lifetimes cry out to me with each touch. I can’t stop. As each story ends, voices of the dead transform into voices I have known all my born days. ‘I cry because I am a niece … a cousin … a sister … because my brother.’

It is at this moment that Bebe realizes she must return Bryan, Texas, and her destiny. That, as Eleanor Roosevelt once told her at Howard University, “you have more, therefore, you must help those who have less.” And Bebe does return, with her husband, Juan, a doctor himself, to work with her father in one of the most racist places in America. Can you please fill us in on the rest of Bebe’s life, and your relationship with her?

My aunt considered her romance with Juan to be the greatest achievement of her life. My five cousins told me that it wasn’t surprising to round a corner in the house and find Bebe and Juan dancing together or canoodling on the couch. Even though they were two busy physicians, activists, and the parents of five, Bebe and Juan were mindful of how their bond helped them face the seemingly insurmountable challenges of their day.

My aunt’s dream of becoming a librarian never came true, but she always had a book at hand, usually a mystery novel. Nevertheless, her fifty-five year medical career was storied. As an OBGYN and then as a psychiatrist, she treated professional athletes, dignitaries and celebrities. She helped train protesters to withstand the psychological tortures of the infamous lunch counter sit-ins. She worked with death row inmates, trained policeman at the academy, ran an addictions clinic, and helped abused women find their way back. She even made house calls.

She skillfully bonded with people to heal them. She never refused to take a patients call or turn an uninsured person away. Her psychiatry degree, I should add, was from Yale, and she was the first Black woman to be the Clinical Director of the Southeast Cleveland Community Mental Health Center, and the first to become Medical Director of Woodruff Hospital in Cleveland, among other appointments.

Because of all this, she was one of the elders invited to President Obama’s first inauguration. But as I mentioned, she was too humble, not to mention practical, so she did not attend because she thought it might be too cold. I asked my cousins where the invitation was. They told me she probably used it as a bookmark. I was not surprised.

As for our time together, it allowed me to better understand my country’s history, and my complex relationship to it, in a vivid and personalized way. Even the inhumane stories were laced with a kind of hope that reframes how I look at what’s happening in our world today. It changed my life for the better, and I wanted to share these revelations with a wider audience.

This Dickens’ quote from A Christmas Carol seems especially apropos to the story you tell in Returning the Bones: “Everything that happens shows beyond mistake that you can’t shut out the world; that you are in it. You get yourself into a false position the moment you try to sever yourself from it; you must mingle with it, and make the best of it, and make the best of yourself in the bargain.” Please talk about your ideal reader? Who do you hope reads Returning the Bones and why?

Oh, that question! I’ve been fortunate enough to receive tremendous feedback from tweens and ninety year-olds, from physicians, from a Vietnam veteran, from a rabbi, from Gen Z readers, from Black entertainers, and more. Because this is an election year, however, today my ideal reader is someone who feels disenchanted with what it is to be an American right now and who struggles to see beyond today’s new headlines. There is a saying from the Talmud similar to the Dickens quote along the lines of “It is not your responsibility to finish the work of perfecting the world, but you are not free to desist from it either.” It’s like when Grandmother Sarah says, “You may not see the change you want happen in your lifetime, but change will come.” It is implied, I hope, that participation is necessary for this to happen. Bebe has plenty to complain about, and rightfully so, but when she meets characters who have lost their countries, their communities, and even themselves to a degree, it puts things in perspective for her about what she feels her purpose in life to be. I would like readers to feel this same inspiration.

What is your life like now? Are you working on another writing project?

My current project is a play entitled Living IncogNegro which I’ll be performing at Key City Public Theater in Port Townsend, Washington. I am also working with two local arts institutions to create an MFA program for actors as well. Otherwise, I am teaching voice to actors all over Seattle and doing readings of Returning the Bones here and there. The reading I’m most excited about is going to be at the San Antonio African American Book Festival where I will be the keynote speaker. Even better, it’s happening near my Great Aunt Prudence’s library!

And remember how I mentioned that this whole endeavor began because I wanted to find family? Because of this journey, I have met over fifty new family members in 2023 alone. I never dreamed this would happen!

Matt Sutherland