How to Rescue Real Science: Add Poetry

There may never be a better time than today for a meeting of poetry and science, especially when it comes to conservation. With science under attack by the US government, and conservationists bravely speaking out about climate change despite attempts at the highest levels of government to silence them, now is also the time to capture the public’s imagination about what should be preserved and what could be lost.

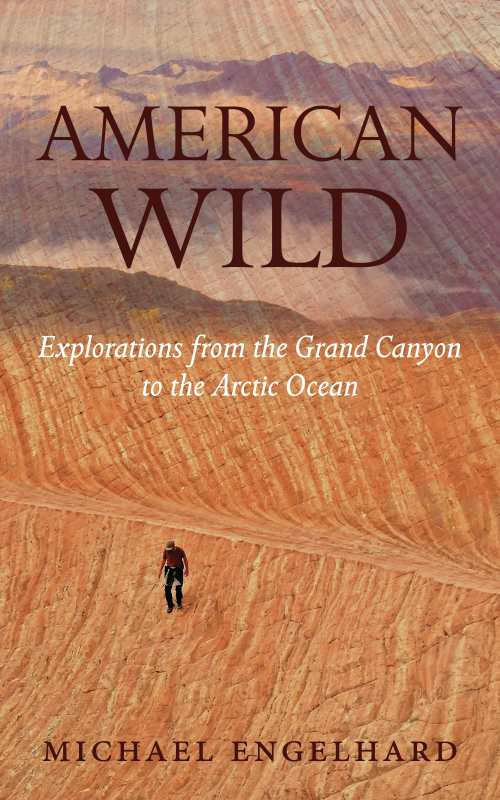

It may not be enough to simply talk about the science of conservation, since facts appear to be inconsequential to many. It might just take poetry, too, to rouse the nation around the idea of nature preservation. That’s where Hiraeth Press comes in. In their tenth year as a publisher, they’ve found a balance between poetry and science. We review their latest book, American Wild in our upcoming print edition, and below we talk to Jason Kirkey, founder of Hiraeth Press, who talks about this marriage of poetry and science in this modern political age.

Do you expect hard times ahead for conservationists in light of political changes in the United States?

Jason Kirkey: 'Let's look at these times instead as a challenge to better communicate the value of conservation ... rather than getting mired in the muck of enmity and partisanship.'

The past decade and change has brought with it an ever-rising awareness of the ecological crisis we currently face. The challenges ahead come like the backswing of a pendulum, but I have faith also in the larger arc of things. The larger arc has been swinging steadily toward an increasing environmental ethic, slow and frustrating as it may seem at times. We have work to do to keep that arc circling and swinging, despite whatever setbacks, disappointments, and heartbreaks may come our way.

Part of the task we are faced with now is finding new ways to build bridges between conservation and the anthropocentric priorities—the economy, human health, jobs—that mark this particular moment of time in the United States. Let’s look at these times instead as a challenge to better communicate the value of conservation and the interrelatedness of ecological and human systems, rather than getting mired in the muck of enmity and partisanship.

One does not ordinarily think of America as a place where anything is truly “wild” anymore, nor a place to discover anything new. What attracted you to Michael Engelhard’s American Wild?

Wilderness is dwindling to be sure, but we are fortunate to have wide swaths of it remaining here on the North American continent. I often think that wilderness is a category of place, but that wildness is the deeper quality that marks a place as wilderness, like wetness is a quality of water. Wildness is like the Chinese concept of dao. You can divert it for a time, but it’s going to keep flowing like a river and, left to its own devices, will eventually erode what interrupts it or divert around it.

Evolution, for instance, is a fact of life and is at work even in our most urban environments. The wild is not just in the land; it’s in people and it’s in language. It is a quality I saw in American Wild, which attracted me to it. When Michael writes of the Southwest and of the Arctic, I can feel a wildernesses in my own mind unfurl within me. That kind of writing—writing that evokes the latent wildness of the human and reconnects us with the wildness of the earth—is why I do this work.

What does Hiraeth mean and how does it tie in with your mission?

Hiraeth is a Welsh word that literally translates to “longing,” but it also has a long and storied history in the Welsh literary tradition, where it has been used to describe a deeper, more spiritual kind of homesickness. A sense of homesickness for the wild and longing to feel our innate but often repressed connection and kinship with the earth and all its myriad inhabitants is what the hiraeth of Hiraeth Press refers to. The books we publish all seek to explore this longing in one way or another.

How can you effectively tie science together with poetry? It is a very rare scientist who is also a good poet and vice versa.

If we are to understand the world and our place in within it, then we need both science and poetry. They are complementary epistemologies. If you want to know how much nitrogen an oak forest releases annually through leaf litter, science is the logical tool for the job. On the other hand, if you want to know the meaning of an oak forest and how we might live ethically and aesthetically in relation to it, then you must learn to listen to the poetry of things and find your place within that relationship.

Both types of questions and both types of answers, I believe, are essential to our future on this planet. It is indeed rare to find a scientist who is a good poet and a poet who is also a good scientist, but in these uncertain times I think that is exactly what is necessary. We need both knowledge and wisdom for the task ahead.

Do you have a favorite author, from any time in history, who successfully combined conservation with poetry?

Though Henry David Thoreau’s verse never reached the height of his prose, his writing in many ways epitomizes poetry—his way of seeing through the surface of the world to the deeper currents of the wild. He was also a keen observer of the natural world and, as many people forget, a consummate scientist.

It was Thoreau who first set down our modern understanding of ecological succession, the way ecological communities and their constituent species change over time. His records from Walden Pond of various species’ flowering over time have also helped researchers understand the impacts of climate change through comparisons with current records. And his fingerprints are all over our modern conservation ethic and aesthetic (“in Wildness is the preservation of the world,” he famously wrote). The poetry of his words continue their reverberation through time.

I would also point to Gary Snyder as a contemporary figure who has married the voices of poetry and conservation. I think what both of these figures have in common is an orientation toward listening to the earth. When you listen to forest, mountains, rivers, stones, you hear poetry. Naturally, you learn to speak poetry back. What else but an inclination toward conserving wild systems could come from that?

Howard Lovy is executive editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow him on Twitter @Howard_Lovy

Howard Lovy