“I hear its echoes everywhere”: Outside Women author Roohi Choudhry on her novel’s titular phrase, claiming kinship & more

Reviewer Kristine Morris Interviews Roohi Choudhry, Author of Outside Women

What does kinship and solidarity look like for women on society’s margins?

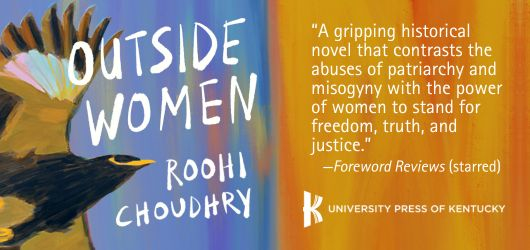

In her novel Outside Women, Roohi Choudhry explores the hardships misogyny and patriarchal systems place on two women migrants separated by geography and time, but also underscores the liberation that can be won through female solidarity. This “gripping” historical novel, Choudhry’s debut, earned a starred review from Kristine Morris in Foreword’s March/April issue, and we were thrilled to connect reviewer and author together for a conversation when the opportunity came about.

Let’s begin with a bit of backstory:

Your first novel, Outside Women, traverses countries and generations to link the stories of two women, each bearing a secret that, if revealed, would serve justice but imperil her life. Sita was born in late-nineteenth-century India where a catastrophic flood devastates her family. After the death of her parents, Sita, unmarried and unloved, lives in her brother’s household under the rule of his tyrannical wife, who makes it clear that her presence is a much-resented burden. Seeking escape, Sita signs away five years of her life to indentured servitude in South Africa—one of the millions taken to different parts of the world after the British Empire abolished slavery. There she witnesses acts that demand justice and must decide whether or not to take the risk of revealing what she knows. Her story alternates with that of Hajra, a contemporary Pakistani woman academic and researcher whose political stance puts her in opposition to her own brother, who will stop at nothing to claim power. Witness to an attack she suspects was meant for her, she flees to New York and then to South Africa. In the course of her research on indentured servitude, synchronicities entwine Hajra’s life with that of Sita as she, too, is faced with a perilous choice: whether or not to stand for truth and justice when doing so would endanger her life.

What inspired you to tell the story of these women?

I’m a multiple migrant—I grew up moving between Pakistan, Zimbabwe, Botswana, South Africa, Dubai, and moved to the United States as an adult. For me, migration has never been a linear story and I’ve always been obsessed with the crisscrossing of our various diasporas across time and space.

This particular story took root when my family first moved to Durban, South Africa, when I was thirteen. I was used to attending international schools with classmates of many backgrounds. But in Durban, just before the end of Apartheid, I was compelled to attend an “Indians-only” high school. I was fascinated by the people around me and they were fascinated with me because few foreigners came to live in South Africa at the time. Teachers would come up to me and ask me to speak Urdu or tell them about Pakistan. As the descendants of long-ago migrants, most did not speak a South Asian language. I was intrigued by the stories of my neighbors and classmates and wanted to know more about how this vibrant community came to be here.

Those experiences began my life-long obsession with the history of the indentured labor system that took Indians around the world, including to Durban. During the writing process for this novel, I began to realize what that obsession was all about—that connecting past and present migrant women’s stories was a way for me to reckon with the forces that had shaped my own life and scattered my family around the world. And that joining these stories and highlighting their parallels could allow me to claim kinship with women long before me who stepped “outside” their cultural norms to migrate on their own.

Tell us about your writing and research process. How long did it take you to finish Outside Women, and how did you manage to make time for writing a novel amidst teaching, your other writing, social activism, and more?

This book took a very long time to write and to sell! Almost twenty years ago, I was lucky to be invited to Hedgebrook, a writing residency for women in Washington state. It was a transformative experience, especially because it was one of the first times someone had taken me seriously as a writer. I began scribbling my first ideas for Sita’s story there.

But then, I put it aside, focusing on short stories instead. I still had a lot to learn about craft. Five years later, when I was in the last year of my MFA program at the University of Michigan and had some time to focus on a longer project, I picked up Sita’s story again. I wrote and threw out many attempts at a draft. But eventually, I found my way to Hajra and some flickers of understanding this story. It took me another eight years or so to draft and revise it, in the middle of full-time work and other demands.

Through those years, I snuck writing into lunch breaks, evenings, days off. It was hard to keep going without much in the way of external validation. Most of the significant progress I’d make would be at artist residencies, when I could really focus.

The story is a moving epic tale, filled with strong sensory imagery and profound emotion. How did you cope with the emotional aspects of writing this book?

The writing process was definitely an emotional rollercoaster. Unlike with other challenges in everyday life or work, I found it hard to talk about these emotions. It’s pretty awkward to talk about emotions brought on by a story I made up! Thankfully, a few dear writer friends could empathize and also knew the characters well. Talking to them regularly was essential. It was often a kind of therapy we were providing one another.

There’s a section of the book that I found especially hard to write and I kept procrastinating going there in my mind. It’s the scene involving Vasanthi and Mrs. Dickinson on the plantation. I put it off for months—I felt anxious every time I even thought about it. Then, someone gave me an excellent piece of advice: write about the scene like a journalist reporting on it, with a sense of distance and a focus on “facts.” I gave that a try and it helped me to make my way through the scene and get it down on the page. I revised it a lot later, but that technique was crucial to approaching the emotional space of that scene.

Please tell our readers what is meant by the term “outside woman.” Is the term still in common use today, and what power does it have to keep women subservient? What can happen to those who defy cultural, familial, social, and/or religious expectations today?

It’s not a common term in speech, but I hear its echoes everywhere. An outside woman is someone who steps outside the confines of the role our patriarchy specifies for her—in the context of work, family, and public space. It speaks to women’s erasure from the institutions where power lies, and how we can rise up in solidarity with one another on the outside, on society’s margins.

I hear the echoes of this phrase everyday here in the United States where a man who brags about rape can still take the highest office in the land. Where so many women can only work outside the home if they pay for private childcare while earning less than men across the board in almost every profession. Where migrants are exploited into dangerous conditions outside regulation because of the threat of deportation.

There’s an expectation—especially placed on immigrant women writing about other countries—that the struggles we write about are only happening to faraway women in desperate circumstances. That “outside women” live in the past or across the ocean. But the stories I write speak to the challenges that all of us subject to patriarchy face right here.

I hope my book can help illustrate how all of our struggles and our ultimate liberation are intertwined across time and space. I’m inspired by aboriginal activist Lilla Watson’s famous quote: “If you have come here to help me you are wasting your time, but if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”

How close to real life are your portrayals of the difficulties faced by Sita and Hajra, each in her own century?

I did a lot of research for Sita’s story—especially influential were Goolam Vahed and Ashwin Desai’s Inside Indenture, Gauitra Bahadur’s Coolie Woman, and Prinisha Badassy’s academic work on indentured laborer women who worked inside colonial homes in Natal. While Sita’s story is not based on a specific person in history, most of the texture of what she goes through is composed from the history excavated by these scholars.

But it’s important to add here that Sita’s story is not just one of “difficulty”—the book is about joy as well, and especially migrant women’s agency in taking command of their own lives.

In what ways have the political situation and treatment of women in Pakistan and other countries with similar root characteristics changed since Sita’s story took place? In what ways have they remained the same?

Sita’s story takes place in southern India and South Africa, so the book does not explore what the region now known as Pakistan was like in the nineteenth century. However, all of south Asia is irrevocably transformed by the legacies of colonialism, and every character in this book is affected, just like all of us in the real world.

Sita is taken from her homeland by the agents of British colonists. Hajra’s story, which takes place in Pakistan, is rooted in the upheaval of south Asia’s partition by the British which turns her family into refugees. The famines faced by Sita’s family in south India have been well-documented as manmade disasters inflicted by the British. Obviously, the political situation has changed dramatically since independence, but we’re still moving through the ripple effects of that violent colonization and everything that was taken from us.

What is there of you in Sita and/or in Hajra? Would you have made the same choices they made under the same or similar circumstances? Why or why not?

There’s very little of my own lived experience in Sita’s and Hajra’s stories. For me, fiction is a way to process my emotions and ideas through a different storyline.

In your acknowledgements, you wrote, “I’m glad I didn’t know what this book would cost me when I started it almost fifteen years ago.” Please share what you can about those costs, what they were, and how they affected you. Knowing what you know now, would you do it all again?

I loved the time I got to spend with Hajra and Sita and I miss them more than I can say. The cost I’m referring to was less about the writing process, and more about how hard it is to be a writer in this world.

I believed in this story always, sometimes single-mindedly. Once these characters got hold of me, I felt a sense of deep obligation and purpose to bring their voices to life. That meant a great deal of pressure to make time for writing and revising—sacrificing promotions and vacations to do the book justice. Many writers, and especially women writers of color, will be familiar with these sacrifices. Jean Rhys famously said if she could choose whether to be happy or be a writer, she’d choose to be happy.

Later, when I got the manuscript as far as I could, it took me many years to find a publisher who believed in it as well. My agent and I dealt with eighteen months of rejections before we found the book a home. That process was incredibly hard on my mental and physical health, and I don’t know if I’d choose to go through that again.

Can we hope for another book? If so, what might it be about?

I’m never short on ideas—at the moment, I’m in the middle of three books at various stages of completion. I make ceramics and I’ve been fascinated with writing nonfiction about the relationship between clay, our bodies, and our spiritual lives. Last year, I spent several months learning about and then helping to stoke a large wood-fired kiln as research for this book. I’m also drafting a book of personal essays about place and migration, and a third book of speculative short stories about women and the wild. I also recently wrote a picture book about grief.

Whether or not I have the stomach to take any of those books through the publication/rejection cycle again remains to be seen!

Outside Women

Roohi Choudhry University Press of Kentucky (Mar 25, 2025)

Two women, their lives separated by a century, learn the meaning of standing witness to horrific injustice in Roohi Choudhry’s epic historical novel Outside Women.

In 1890s India, after the British abolish slavery in their colonies, over one hundred thousand poor Indians are sent to South Africa as indentured servants. Sita is one of them. Forced to flee her family’s ill treatment, Sita signs away five years of her life in the hope of making a better place for herself in a strange new world, only to find that abuse, disrespect, and oppression followed her.

A century later, Hajra, a Pakistani scholar, flees her home in Peshawar after an acid attack meant for her disfigures another woman. Doors open for her to further her research on indentured servitude in New York. Startling synchronicity leads her to South Africa, where her story entwines with Sita’s. Both women hold dangerous secrets that, if revealed, would require bearing witness to life-threatening truths.

The novel is set amid clashes between rival ideologies and ethnic and class-based prejudice. Cinematic in color and scope, it reveals how the politics of patriarchal systems, religion, and family and social customs yoke women. Its revelations are made more poignant in considering that the century between Hajra and Sita resulted in so little change.

Outside Women is a gripping historical novel that contrasts the abuses of patriarchy and misogyny with the power of women to stand for freedom, truth, and justice. Notable for its emotional depth, lively pace, and smooth transitions as it moves across time and continents, this complex, nuanced story rises above its graphic descriptions of torture inflicted on those who dare to defy conventions to celebrate the strength of women and the warmth of human friendship and loyalty.

Reviewed by Kristine Morris March / April 2025

Kristine Morris