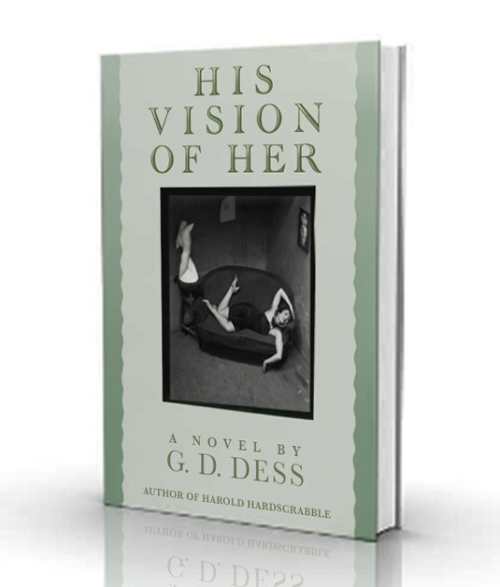

I Rereleased My LGBTQ Book From the '80s; What Has Changed in 30 Years?

Editor’s Note: This commentary is part of a special focus on LGBTQ books, publishers, and authors for the month of June.

His Vision of Her was first published almost thirty years ago, in the mid-1980s. Ronald Reagan was president. The Twin Towers were still standing tall. The first space shuttle, the Columbia, went up. The Berlin Wall came down. The AIDS epidemic raged. People smoked in public places, in bars, restaurants, and offices. Electronically we were still in the dark ages; the Internet was in its infancy; there were no cell phones as we know them today.

My publisher at the time, Harper & Row (today HarperCollins), put advertising dollars behind His Vision of Her. My editor had high hopes for the book. The publicity department arranged for me to participate in Scribner’s new author gala. I was one of the twenty-three writers of contemporary fiction invited to “one of the largest [book] signings ever held in Manhattan.”

But the mainstream book publishing world and the reading public were not receptive to books with LBGT characters. Despite the hoopla, sales were dismal. Now, decades later, the advances made in sexual politics have made the atmosphere for alternative lifestyles more acceptable (I won’t say mainstream) and when the copyright reverted to me, this change encouraged me to republish the novel on a small, independent press. What follows below is adapted from the preface of the new edition, which provides today’s readers a history of the book’s reception. Hopefully this time it will be different.

Reviews Reflected the Times

His Vision of Her was first published in 1988 and the prepublication reviews were, for lack of a better word, mixed. Publishers Weekly offered one quotable sentence: “Dess charts the cultural geography of New York’s downtown art scene with care and arch wit.” The Kirkus review was no better: “Dess’ wonderful social observations are marred by slack pacing and overabundant explanation. A satisfying read, however—particularly if big-city manners are your cup of gin.” Later, while the book was being returned to the publisher by bookstores, the New York Times Book Review came out with an unqualified, positive review: “Mr. Dess considers art and authenticity, love and exploitation, appearance and reality. It is a tribute to Mr. Dess’ technical precision and to his compassion that, even though the medium of Stephen’s rarified vision of Gilberte, we get an indelible and poignant vision of them both.”

The Times review was too late to help. My agent said it was unfortunate that the early reviewers had immediately tagged the novel as either “gay” or “bisexual” or both. These designations were, in fact, practically the first thing to which the reviewers called attention. The Kirkus Review called it out in the first sentence, and then later decided that the narrator, Stephen “is more gay than bisexual.” In the first sentence of the Times review the narrator is labeled as “bisexual.” Publishers Weekly was somewhat more circumspect, and waited until the third sentence to announce that Stephen had sex “mostly with men.”

Without saying any more than the above, these sexual labels preemptively negatively classified the novel. Thirty years ago, the “tags” and descriptive acts (sex mostly with men) used in the reviews served as both a warning to straight readers and a means to sidetrack the book away from mainstream literature into the then little-read, sub-genre of “gay lit,” although the latter term was not generally used at the time; nor was LGBT, which only came into widespread use in the 1990s. Back then “gay,” and “bisexual” were highly politically charged identifiers. And men having sex with men was certainly not something people who read literature wanted to read about. There terms, used in a book review three decades ago, warned potential readers, without evidencing overt homophobic prejudice, that this book wasn’t for them if they felt uncomfortable reading about alternate lifestyles or non-traditional representations of male and female sexuality. And, at that time, this represented the majority of the country—it may still today.

Refusing to Wear Labels

However, while the reviews labeled the principal characters in the novel, Stephen, Gilberte, and Kristine, refused to wear them. Kristine is married but takes Gilberte as a lover. Gilberte, who at one point is living and sleeping with Stephen becomes Kristine’s girlfriend, but then goes back to Stephen. When we last see her, she is planning to marry a man. The novel portrays both Kristine and Gilberte as having a visceral understanding of their sexuality; they never stop and try to analyze it, they just live their lives. And nothing prevents them from following their desire—especially when it coincides with their quest for power and success. They don’t fuss and bother about whether they are “lesbians”; the question of their sexual identity simply doesn’t interest them; they are more interested in trying to “make it” in New York.

Stephen is different. He questions everything. The instability of his sexual identity perplexes him. He sees it as an object like any other, and believes it should yield its truth to rational analysis, which it refuses to do. And, he becomes trapped in a dialectic that permits no movement: “…when your existence was unclassifiable how could you arrive at the essence of who you were? How did you move on? How did you do anything?” These questions paralyze him and can make him appear, as Publisher’s Weekly complained, “maddeningly passive.”

What was perturbing about the initial reviews—which turned out to be the only reviews—was the signal it sent to potential readers. Because while the characters’ sexual instabilities infuse the narrative, they are not the main concern of the novel. What is His Vision of Her about? The Times review did finally identify the major themes of the novel: “art and authenticity, love and exploitation, appearance and reality.” The interplay between Stephen’s desire for Gilberte (to remain true to her artistic vision), and his distaste for her commercial aspirations (fueled by the social-climbing Kristine) drive the narrative and the psychological dynamic throughout the novel. Thus, a disservice was done to readers interested in these themes by insinuating that the work’s main interest was a narrow one, that of “alternative lifestyles,” rather than an examination of the cultural milieu in which art is made and sold in New York.

But times change. The political issues surrounding sexual identity have (more or less) sufficiently evolved so that—to judge by the reviews to date—early readers of the new, second edition are focusing on the larger themes of the book rather than the character’s sexual identity. And that’s a good sign of the times.

G. D. Dess is an author, critic, and essayist. His most recent novel, Harold Hardscrabble, has just been published.

GD Dess