In Which I Confess My Fascination for Queer Gang Members & Menstruation Envy

Editor’s Note: This commentary by Editor in Chief Matt Sutherland is part of our special focus on LGBTQ issues in the month of June.

Emotionally, physically, amorously, you name it, the whole gamut of LGBTQ life experience comes with as many variations as for people with blue eyes, brown hair, or chubby cheeks. Humans, after all, are human, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender. And you can bet the farm that at some point in the near future, the “who do you love, how do you love ‘em” question won’t merit much attention at all. Condemnation is increasingly giving way to tolerance and inevitably will arrive at indifference.

Look at the encouraging number of out candidates elected to British Parliament in 2017. A record forty-five members of the LGBTQ community now call themselves members of parliament (7 percent), and, in fact, their same-sex orientation seemed to enhance their electability, particularly for those running in the Labour Party, Conservatives in competitive districts, and rural candidates. Most encouragingly, the Scottish Conservative Party is headed by Ruth Davidson, a Protestant, lesbian unionist, who will soon marry her Irish Catholic partner. Gotta love change.

But lesbians, gays, bisexuals and transgenders are still exotic creatures to much of America and the world, and we can blame that on willful, head-in-the-sand ignorance; existing restrictive laws on marriage, bathroom choice, sexual practices (sodomy), etc.; religious teaching; and unabashed intolerance. Discouragingly, the LGBTQ community still spends much of its existence in closets and shadows and lots of places you wouldn’t expect them to be due to entrenched stereotypes.

Like the hyper-masculine, heterosexual, misogynistic world of gangbangers. We’re not kidding.

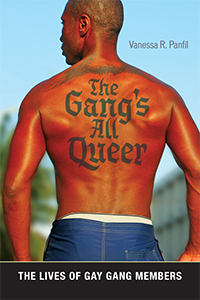

Columbus native Vanessa Panfil caught up with fifty-three male gay gang members in and around the neighborhoods of her hometown in The Gang’s All Queer: The Lives of Gay Gang Members (NYU Press), a riveting look at identity construction, the qualities of “real” men, boundary maintenance (the things we do to present ourselves as we’d truly like to be seen), and so many other nuanced components of the gay criminal lifestyle.

Nearly all young men of color, she studied tattoos, manners of dress, gay bars, vogue dancing balls, selling drugs and sex, dating, fighting, how gay men blend into straight gangs without coming out, and gang rituals. All of which offers a fascinating peek at a terribly complicated world, and yet, Panfil notes, there is something about “recent cultural history that has facilitated gay and bisexual gang members in straight gangs feeling comfortable enough to talk with media, documentarians, and researchers.” These stories are needed to change public opinion. A more tolerant society is the prize.

Her stories of men dressing in drag to entice johns on the street are graphic and heartbreaking. In fact, much of this project spotlights unfathomable lifestyles and is uncomfortable to read. But then, is it fair for us to judge someone for thinking that fifty bucks is fifty bucks whether earned flipping burgers at McDonald’s or turning a quick front seat sex trick? (That was a tough sentence to write, but seriously.) Tolerance is tricky. Every one of us has a picture in mind of how we’d like to be seen by others.

Along the road to maturity and adulthood, we all developed a keen, highly subjective sense of female and male beauty, right and wrong as it relates to sexual behavior, and simple triggers for what we find offensive—women shouldn’t wear skirts that short; men shouldn’t wear skirts that short; I support his decision to be a woman but why does he need to speak falsetto and act so flamboyantly; etc. In the main, repulsion is a tough trait to shake, but try we must.

If the highest praise is reserved for books that cause us to question deeply held beliefs, this book ranks among the best.

Love for Lesbian Poetry

Given a choice, I’ll read LGBTQ poetry over the straight stuff any day—and not because I’m a LGBTQ member and want to express my loyalty to teammates. In fact, I don’t know why so many lesbian and transgender poets appeal to me. Perhaps, there’s a subconscious voyeurism at work. Not from a sexually piqued standpoint, but rather the LGBTQ crowd seems exotic and lesbian poets especially are highly skilled at articulating the uniquenesses of their lives in compelling, relatable ways. Or, perhaps I secretly like the response I get at cocktail parties when I express my love for lesbian poetry, though I can’t remember ever doing so.

It is, as they say, what it is, and my latest fav is Judy Grahn, the author of a new collection titled Hanging On Our Own Bones (Red Hen Press).

Hugely, widely acclaimed, Grahn is a distinguished prof of Integral and Transpersonal Psychology at the California Institute of Integral Studies in San Francisco. A social theorist, she writes, “I have wanted to be transgressive in my poetry, incorporating both real-life conditions and goddess mythology, going directly toward critiquing white supremacy, honoring battered women, exalting the powers of menstruation, conflating all labor with birth imagery, and revealing lateral hostilities among potential allies—all in order to arouse meaningful social critique.”

I’m suddenly bummed at not being able to menstruate. Thanks a lot, Judy.

Here’s a short excerpt from “Crossing,” a new work that will be part of her upcoming “book-length poem tracing Helen of Troy back in time to goddess Inanna of Sumer, and forward in time to Helena of the Gnostic writings.”

THREE

Oracle:

She reported what she had seen

and heard to the apostles, who could

hardly believe her at first.

Magdalen’s message was that

something lives over on the other side

that sends us love (and further that these forms

we occupy just now, are not the only ones).

Magdalen’s message was received; at first her heart

was golden. Chastity, fidelity, obedience

became her habits.

Yet in the centuries after, she was so degraded,

disregarded, all the credit given to the vision

rather than the visionary, just as people

in a township drink the water everyday

and don’t recall the engineer who found

the aquifer and dug the well … yet worse, imagine

hatred for the engineer, calling him a thief …

as Magdalen could tell you, those who believe

in paradise believe also in its opposite,

and those who love sacrifice love suffering,

then long ceaselessly for comfort.

Let’s turn now to a goddess with a different

philosophy. One whose adventures here on earth

inevitably include rising

and falling, and rising

and falling …

Matt Sutherland is Editor In Chief at Foreword Reviews. You can e-mail him at matt@forewordreviews.com.

Matt Sutherland