Indie Authors are First to Rattle the Cage for Criminal Justice Reform

Maya Schenwar always suspected, in theory, that something was wrong with the US prison-industrial complex, knew that our policy of mass incarceration wasn’t working. At least, she knew all the progressive talking points. But it wasn’t until Schenwar’s own sister became caught in the gears of the prison machine that she realized that the US criminal justice system didn’t need to be fixed; it is wrong on so many levels, it needs to be torn down and rebuilt from the ground up.

Maya Schenwar

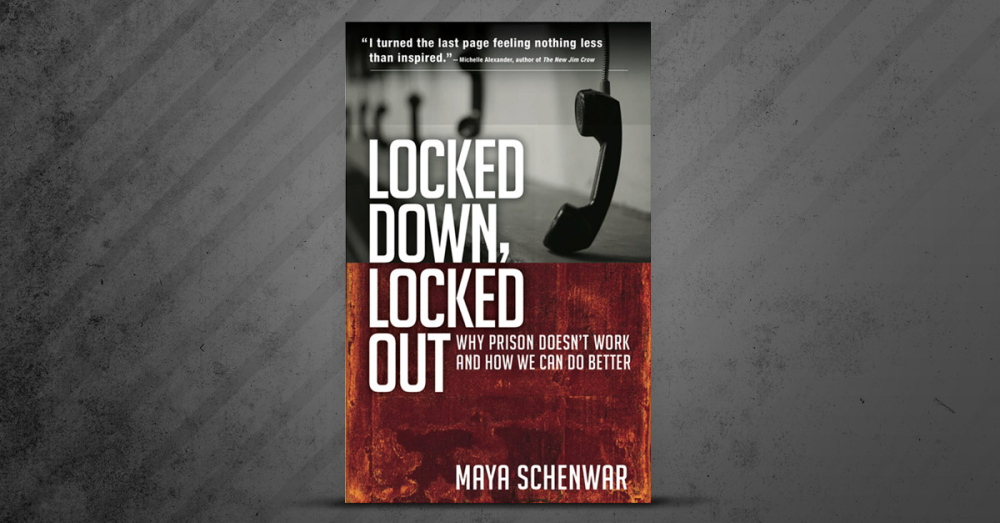

Schenwar is among a new wave of independent authors drawing attention to the disease of incarceration plaguing the nation. Her book, Locked Down, Locked Out: Why Prison Doesn’t Work and How We Can Do Better, expertly weaves the story of her sister’s plight with a broader picture of just how the mass incarceration epidemic of the last couple of decades has not made us safer and has cost the United States dearly in wasted lives, broken families, and vanquished cities.

This may be the year real criminal justice reform begins to happen—when everybody from progressives to a Koch brother agree that the system is broken. It may be the unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, and New York City over out-of-control law enforcement or it may be the high cost of incarceration that’s bankrupting state budgets. I suspect, though, that it just might be because the United States locks a higher percentage of its population behind bars than any other civilized country; that more are seeing, firsthand, just how devastating the system is to families and communities.

“I think definitely the situation with my sister complicated this issue a lot for me in really important ways,” Schenwar told me in a phone interview. “It’s an issue that’s so wrapped up in our psyches, that getting outside of it, and also getting society outside of it, requires a kind of rethinking that it’s much more massive than just accomplishing these talking points and changing a few policies.” In other words, when it effects you personally, you can see all the way across the system and what kind of a massive undertaking it would take on every level to fix it.

And it also makes for a pretty compelling book. It is this personal struggle that gives Locked Down, Locked Out its power. Through her sister’s eyes, we see struggles with drug addiction and how prison is set up for punishment, but not for healing. We see how, through background checks, her sister is unable to find a job when she leaves prison, how incarceration fails to prepare inmates to live outside once they’re released, how many women find it easier just to come back, and how her sister gave birth to a child behind bars.

Her sister’s story is told in the context of larger stories of lives, communities, families torn apart. “I wrote the book to tie all those things together—my family’s experience, the larger national picture, and also the experiences of the people that I correspond with, my pen pals in prison,” she said.

It’s a book that, Schenwar said, she could not have written for a larger publisher. The indie house Berrett-Koehler was perfect for her and fits in with her day job as editor-in-chief of Truthout, an independent progressive news site.

“The book I wrote broke some of the rules of writing about prison in the mainstream,” she said. “One rule is that when you write about prison, you have to write with the assumption that prison can be fixed and that the prison system is broken. I was starting from the assumption that this prison-industrial complex that we currently feed doesn’t need to exist.”

She also did not “pretend to be objective.” She “opted out,” she said, of writing about the alleged crimes of the people she spoke to in prison. “The way the justice system keeps records on people is not the way I want to document people.”

There’s a societal assumption of shame against those who are incarcerated, as evidenced by websites that run mugshots solely for the purpose of public humiliation, or requiring those who have served time to tick off a box on job applications so potential employers know not to hire you.

In one powerful scene, Schenwar speaks to her sister:

“Just think about the day you get out,” I say.

She pauses, and I realize again that we are talking about very different things.

“OK,” she says. “But what am I going to do the day after that?”

This is where we are in criminal justice reform. We can all agree that we shouldn’t incarcerate so many people—whether it’s for humane or monetary reasons—but then what? What is the alternative?

Schenwar begins to scratch the surface in her book, with concepts that include “restorative” and “transformative” justice. “Restorative” is community-centered and not based on the power of the state, but on relationships between people. “Transformative” emphasizes a transformation of the conditions that perpetuate violence. Courts are set up to do only one thing: punish those accused of doing harm, but they do nothing about the people on the periphery: the families of the accused who are left behind, or even whether the alleged victim even wants the perpetrator punished.

In many cases, if people would have simply talked to one another, the law would never have had to get involved.

“That’s really the core of it,” Schenwar said. “It’s not just about replacing prison with something else. It’s about thinking at the very root of some of these problems that we’re grappling with, especially violence, that more-human closeness and bringing people together in various ways and building community actually prevents a lot of that stuff at the front end.”

For example, jails and prisons are de facto drug-treatment and mental health institutions. Deal with these issues “at the front end,” through widespread treatment centers, and you don’t deal with the associated crimes on the back end.

It will be a slow process. But, like any addiction, the first step is to admit you have a problem. And it appears as though a consensus is building that this country needs to break its addiction to incarceration. Schenwar’s book is part of a first wave.

Others include: The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness, by Michelle Alexander (The New Press). This book “was the real game changer in terms of getting many, many more people involved in thinking about thinking about prison and racism and the overlap there,” Schenwar said. She also recommends: Are Prisons Obsolete?, Angela Y. Davis (Seven Stories Press); Lockdown America: Police and Prisons in the Age of Crisis, by Christian Parenti (Verso); and Resistance Behind Bars: The Struggles Of Incarcerated Women, by Victoria Law (PM Press).

Today, Schenwar’s sister is in a women’s treatment center, where previously incarcerated mothers can detox and heal … with their kids. And Schenwar is doubling down her efforts to spotlight criminal justice reform on Truthout.

“Looking back on it, the process of writing it was fun and inspiring for me and in some ways was so painful and difficult,” she said. “Every day I woke up and said, ‘I don’t know if I could write this book at all.’”

We can all be glad she did.

Howard Lovy is executive editor at Foreword Reviews. You can follow him on Twitter @Howard_Lovy

Howard Lovy