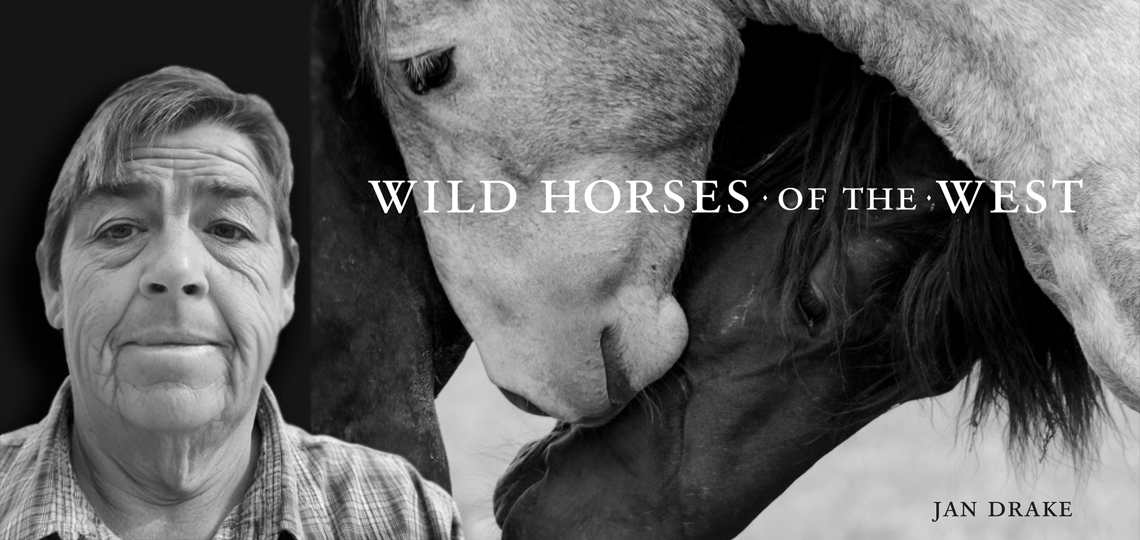

Interview with Jan Drake, Author of Wild Horses of the West

Hail to the wild mustangs of the American West. 95,000 strong, these majestic animals descend from a potpourri of escaped and turned-out domesticated steeds beginning with Spanish horses from the days of the Conquistadors more than five hundred years ago and US Cavalry horses gone AWOL.

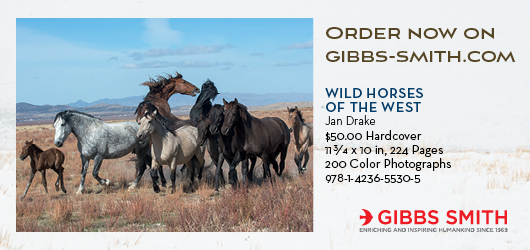

For nearly twenty years, Jan Drake has roamed the open ranges of Utah tracking the Onaqui and Cedar Mountain herds, camera in hand. In Wild Horses of the West, she documents her extraordinary experiences, introduces readers to the ways and hardships of these animals, and lets more than two-hundred photographs capture the moment. We found the book irresistible. Thanks to Gibbs Smith Publishing for help in connecting us with Jan for the following conversation.

First of all, please offer us a primer on wild horses? (Can we call them mustangs?) Where did the wild horse population of the western United States come from? What role did Native Americans play? Once free from their human captors, how did the horses adapt so well to such a harsh, arid region?

Yes they are commonly referred to as mustangs. Today’s population of wild horses is said to have originated from the stock that Cortez brought to North America during the early 1500s and the explorers that followed him. They came from the horses that got left behind when they returned to their home countries in Europe or animals that escaped. In addition, a lot of horses in the herds today are from horses being turned loose or ones that escaped from ranchers and pioneers making their way from the east to start a new life in the west. Lastly, the U.S. Cavalry turned out stock when they received fresh mounts from the east.

In today’s herds, you can see the influence of some of the domestic stock that we still use today. Some of the herds will have characteristics of the Morgan and thoroughbreds that the Cavalry used, while others might have draft influence from the pioneers. You can still see traits of the Spanish horse in today’s herds. Once the Native Americans discovered the horses that roamed the plains, it changed their culture. The Native Americans revered the horse as a spiritual animal and took care in their training and their use. With the horse, the Native Americans could hunt buffalo and other food sources much more easily, and horses also allowed them the ability to trade and barter with other tribes and pioneers for much needed items.

Just like any animal the wild horse learned to adapt to their surroundings. Traveling over rocky or hard terrain to find forage or water had a natural affect on hooves and kept them trimmed. Horses that lived in sandy regions might have a wider foot making it easier for them to travel in the soft sand. As for their forage, a wild horse will eat some grasses that our domestic horses won’t touch. Some of the wild horses that I adopted would even eat the weeds that I had pulled and left in a pile. It’s amazing how they can adapt for survival. As far as water sources, the wild horse will even eat snow to stay hydrated.

When we started the project for Wild Horses of The West, I made it clear that I did not want just a book of pictures. For me this was a once in a lifetime opportunity and I wanted to make the most of it. I wanted people to see the story of the horses on the range and to learn about them. To see the beauty of the landscapes on which they roam, as well as the spirit of the wild horse, but most importantly what they endure—it is a hard life out there!

When and why did you become such a fan of, and advocate for, wild horses?

I was first introduced to the wild horses when I moved out to Utah to see a friend and we would ride his horses out by the wild horse corrals in Herriman, Utah. After seeing the wild horses and learning about their history I thought that someday owning one would be something special. It wasn’t until a few years later that I got really serious about getting back into horses. We had organized an adoption and gentling clinic at the National Ability Center in Park City and that is where I adopted my first mustang, a blood bay mare named Kiss Me Kate (what a color). I watched one of our participants, who was a below-the-knee amputee, work with one particular horse that showed absolutely no interest in anyone else at the clinic except Sam. The bond that happened with those two was instantaneous and Sam ended up adopting this horse, Spud, and they had many years of riding together. The best part of it all was being able to see how Spud would take care of Sam over the years. That is when I realized what a connection the wild horses have to humans.

This clinic is where I started my friendships with the BLM (Bureau of Land Management) Wranglers and others in the Wild Horse and Burro program, spending years following the Onaqui herd and photographing them. About four years ago, I ran into the BLM Horse Specialist and a volunteer from Wild Horses of America out darting mares with the birth control vaccine PZP on the range. After tagging along with them for the rest of the day, my interest piqued. After finding out that it was basically just the two of them trying to vaccinate the herd that I decided to get involved. The BLM offered a darting certification, so a photographer friend and I took the course and became certified to dart. I also got more involved with the Wild Horses of America Foundation and the darting process. We now have nine certified darters and have been able to increase the number of vaccinated mares in the Onaqui herd.

How many wild horses are there in North America? Is the population stable and in good shape? Where specifically in the western U.S. are the wild horses?

As of March of this year, there are about 95,000 wild horses in ten western states; an area that would ideally hold only 27,000 wild horses. A wild horse herd can double itself in just four years but with the delivery of birth control we can slow it down to almost eleven percent annually. However, not all of the wild horse herds are easily vaccinated on the range so other solutions must be found. The horses and burros can be found in Colorado, Utah, Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, California, and Oregon.

If the ancestors to the wild horses were domesticated animals, do you think the horses retain any familiarity or kindred spirit with humans? When you work to gentle a wild mustang, do you sense some intuitive connection?

That is a tough question and depending on who you ask you will get a multitude of answers. In my experience with different herds, the majority of the horses will run away when they see humans since they have had no interaction with humans. For example, we have two herds here in northern Utah—the Cedar Mountain horses and the Onaqui horses—with two completely different mindsets. The Cedar Mountain range has few visitors and the horses will run when they see a vehicle or humans. It is hard to photograph these horses when they are running away from you.

But the Onaqui horses are more habituated to humans and vehicles because of the higher amount of traffic and humans recreating on their range, including an increasing number of photographers wanting to photograph them.

Gentling a wild horse is not an easy task—you have to work on the horse’s time and have a lot of patience, but once you find the connection with the wild horse and they trust you, the bond that forms is amazing. But not all wild horses want to or have the ability to trust us humans. I have had some that just never trusted me completely and the partnership didn’t work.

Describe the personality (or personalities) of wild horses? Are they aggressive, skittish, shy? Do the individual herds or bands of horses have a hierarchy with a leader, for instance?

Wild horse have a wide range of personalities: some are aggressive, most are skittish, while others are curious about human activity and overly friendly. We must remember that even while some horses want to approach humans and seem to want to be your friend, these are still wild, unpredictable horses and must be respected and given their space. Within each herd there are family bands or bachelor bands and within each band there is a hierarchy.

The band will have an alpha or lead mare and a band stallion: the mare is responsible for moving the band to new forage areas or to water while the band stallion protects the band and is responsible for breeding. The band stallion will travel at the rear of the band when the lead mare moves the band. He is there to protect the band and make sure it stays together. There may also be a couple of mature stallions within the band serving to help the band stallion protect the band but that doesn’t mean they won’t eventually challenge the band stallion to take his band away from him. These bachelor bands travel together and often try and steal the band or a young mare out of it.

In the book you refer to several individual horses by nicknames. Do they know you? How do they respond to the camera?

I would say that the wild horses do not recognize people. Some horse lovers think that individual horses might know them but in reality, it’s just that certain horses are so habituated to humans, these folks mistakenly think that they have a personal connection to the horse. As far as the camera, I think certain horses are aware of it and we like to think they are posing for us, but in reality, the horse is more curious about what you’re doing than they are the camera.

The book includes more than two-hundred fantastic photos showing the horses in all manner of behavior, including a great many dramatic photos of fighting. Why do the stallions fight so viciously?

There are several reasons why stallions fight, though mainly it’s to control the herd or to protect their mares and foals. While some fights can be deadly to one of the stallions, most fights end as quick as they begin; only a few last for several minutes. Typically, they consist of a lot of posturing—of pawing at the ground and snorting and striking at each other, while others involve the horses chasing each other around. I have seen a fight that involved the band stallion chasing off another stallion over some distance only to have the challenger return within minutes to challenge him again. Then there are a few band stallions out on the range that the others do not bother to challenge.

You’ve adopted wild horses to use in your work with the National Ability Center, and spent countless hours helping to improve the living conditions of horses with the Bureau of Land Management. What can other horse lovers do to help these incredible animals?

There are many ways to get involved with not only wild horses but also domestic horses that provide much needed therapy to people of all abilities. If you are thinking of adopting a wild horse of your own but don’t think you have the skill set to gentle one yourself, you can reach out to the Mustang Heritage Foundation. A wonderful resource, the foundation offers programs that work with veterans, they sponsor Mustang Challenges where you can bid on a finished mustang that is ready for you to ride, and they have the TIP (Trainer Incentive Program) where trainers will gentle a horse and find an adopter.

If you are not interested in owning your own mustang but want to help keep the herds out on the range, organizations like the Wild Horse of America Foundation work closely with the BLM’s Wild Horse and Burro program and are always looking for volunteers and money to help with their on-range birth control program. Additionally, the Intermountain Wild Horse and Burro Advisor helps new adopters find information on how to gentle a wild horse, and offers resources for all horse owners who need a little help.

The National Ability Center provides equine therapies to kids on the autism spectrum, individuals with spinal cord injuries, and our population of veterans, and is always looking for volunteers, horses, and funding. On the local level, reach out to therapy programs in your own community to help make a difference. I would say go volunteer in one of these programs to see how a horse (gentle wild horse or domestic horse) can make a lasting impact in the lives of someone with challenges. I know that is how my journey started nineteen years ago.

Matt Sutherland

![“Wild horses [are] legendary icons of the American West. Their spirit encourages us to live free and reach for our dreams.” Janet Tipton, Founder, Intermountain Wild Horse & Burro Advisors Gibbs Smith Enriching and inspiring humankind since 1969](https://www.forewordreviews.com/foresights/art/82031-w600.jpg)