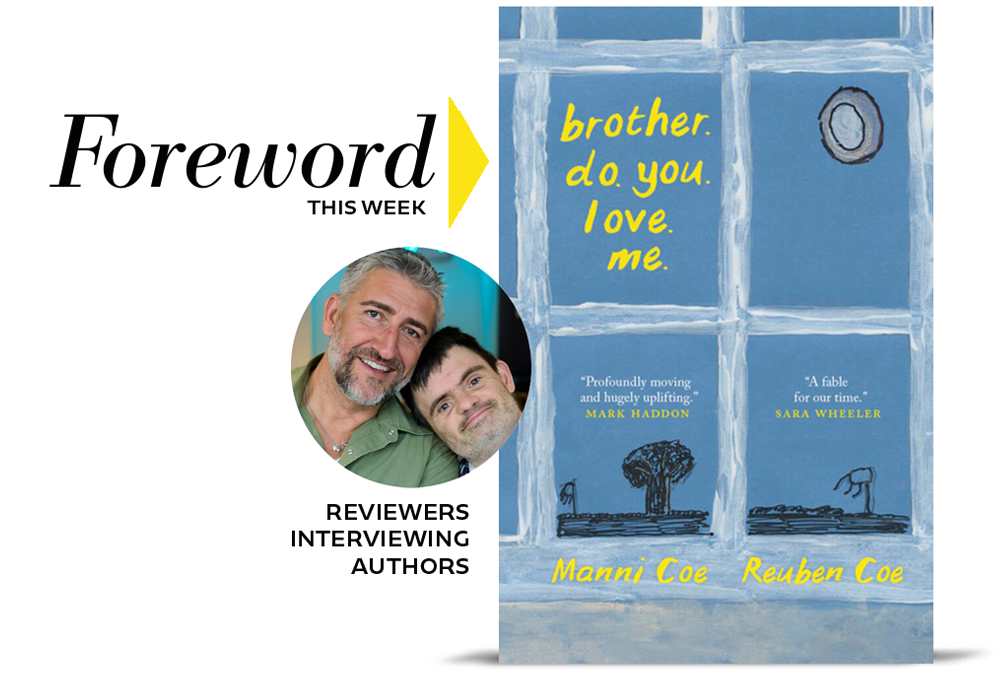

Interview with Manni Coe, Author of brother. do. you. love. me.—A Down Syndrome Song of Praise

“It was always my hope that the book would provide a bridge to a reliable understanding of people with Down syndrome. … My vision is that, after reading our book, every reader will begin actively seeking ways to have contact with people with DS. Everyone needs a Reuben in their life!’’ —Manni Coe

Picture your first day of third grade and your teacher asking each of you to stand up and, one by one, tell the class what makes you special and important. “I have green eyes,” says one, “I’m named Theo after God,” says another, “I throw a baseball with my left hand,” says a third, “I have Down syndrome,” says Susie, and then she beams the biggest smile anyone has ever seen.

It’s a delightful thought experiment to consider how an incident like that could leave everyone with a wildly different understanding and appreciation of learning differences.

In light of recent advances in drug therapy designed to address the cognitive abilities of neurodiverse patients and others, like Susie, who have Down, many parents and experts are asking larger questions about so-called “disabilities.” Are drugs helping these people be who they want to be or are they turning them into who we think they should be?

In an Atlantic article from a few years back, Amy Julia Becker writes about her evolving thoughts on these issues as it relates to her own daughter’s Down syndrome. “I am not certain that Penny needs medical interventions to improve her cognition, but I know she needs a social context that welcomes her. I also don’t know if any drugs for cognition will become available in Penny’s adolescence, and I don’t know whether we would offer them to her. I do know that in the meantime, as the parents of a daughter who sees the world differently, we will continue to challenge ourselves to expand our definition of who belongs.”

And because we love books, we’re going to squeeze in one more quick story from Amy.

“Last week, Penny came home from school with a new chapter book. We sat on the couch and took turns reading pages out loud from Fish in a Tree, by Lynda Mullaly Hunt. The story centers around a sixth-grade girl named Ally who has struggled all her life to learn how to read, and has to

fend off the taunts of her classmates. It turns out Ally has dyslexia. Under the watchful eye of a new teacher, and through an alliance with some new friends who are also outside the social norm, she begins to recognize not only the way in which her brain doesn’t work, but also the gifts she has to offer due to her unusual way of seeing the world. In the midst of this recognition, her teacher says, ‘If you judge a fish on its ability to climb a tree, it will spend its whole life thinking that it’s stupid.’”

On to our interview with Manni Coe, author of brother. do. you. love. me., detailing his extraordinary relationship with his brother Reuben, who has Down syndrome. You’ll find Rebecca Foster’s flattering review here.

Although the contemporary storyline takes place in the COVID years, you don’t attribute Reuben’s mental health crisis to the pandemic. Looking back, do you believe there is any way it could have been avoided? Are these problems endemic to the care system?

We didn’t want it to be labelled as a Covid narrative, so we consciously kept mentions of the pandemic to a minimum. We hoped that our story would resonate with the wider public and that its strongest themes would be relevant for several years. Reuben’s mental health had suffered before the pandemic but his isolation during those tough months exacerbated his condition. There are many problems endemic to the care system. Reuben and I will be addressing many of them in our role as Ambassadors for the Down’s Syndrome Association in the UK. We are honoured to begin working with them to address these issues from the grassroots level upwards.

What do you hope that those unknowledgeable about Down syndrome, or with outdated or stereotyped ideas, will gain from reading your book?

It was always my hope that the book would provide a bridge to a reliable understanding of people with Down syndrome. I have always noticed some people’s reticence to engage with Reuben directly and I suspect that their attitude was based on a lack of knowledge and a fear of saying the wrong thing. My vision is that, after reading our book, every reader will begin actively seeking ways to have contact with people with DS. Everyone needs a Reuben in their life!

How did you decide on the structure of alternating between the present in an English country cottage and earlier moments from your family’s life?

My first draft was a diary format. It was my “Dear Kitty” and a way of purging my stress and worry onto the page. When I began working on the second draft, the narrative naturally opened up and I wanted readers to understand how Reuben was before his breakdown so they would be aware of the colossal loss of his independence and abilities. As we were living in an intense situation in the cottage—several months without any sure signs of Reuben’s recovery—I didn’t want the story to be based in a state of hopelessness. Weaving stories from our childhood and Reuben’s early years into the narrative eased the intensity and oxygenated the reading experience.

The dialogue feels so natural. Did you keep a diary, or notes, during the winter of 2021–22 to enable you to recreate that time?

Once Reuben’s communication and spoken words began to return, each and every word was precious. I did keep a diary of our interaction and wrote our conversations down word for word. They were too precious to forget.

How has the rest of your family responded to the representation of them (and you and Reuben)? Did you have any issues with people opting not to be included or wanting to change things you’d written?

I did have issues with some people’s mentions and inclusions, but I won’t tell you who! I was very aware that, when writing memoir, I needed to be kind and generous with people’s behaviour and involvement or lack thereof. I didn’t want to appear too critical and aimed to give the narrative a positive vibe. I changed many names for anonymity. My dad, in particular, was thrilled at our family’s representation and we have received many comments from readers who fell in love with Reuben and his interaction with me. I wanted the book to feel very real.

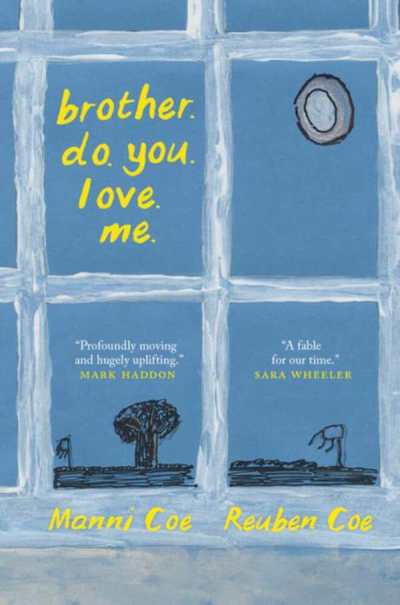

Reuben’s illustrations are such a unique aspect of the memoir. Was it always part of the plan to include his artwork?

Reuben was largely non-verbal throughout our twenty-six weeks in the cottage and every single day he drew me a picture with his felt-tip pens. We still have them all as a collection. One evening, after Reubs had gone to bed, I put them all on the kitchen floor and saw a clear narrative. I remember thinking, “something is happening here.” It was clear that Reuben was drawing his emotions onto the page.

At our first meeting with Little Toller, I took along my manuscript and Reubs took along a pile of his drawings. Gracie looked at Reuben’s art; Adrian began to read my manuscript. Then they looked at each other and it was instantaneous. They decided to publish the story there and then and were adamant that Reuben’s art would feature prominently throughout the book in glorious technicolor.

brother. do. you. love. me. found a home with independent publishers better known for nature writing (Little Toller in the UK and Greystone Books in North America). What do you think this says about the book? (e.g. that it was difficult to pigeonhole, or that place-based writing should be a broader umbrella?)

I think it is difficult to pigeonhole, yes. It’s a memoir that covers a wide array of issues: brotherhood, mental health, Down syndrome, and family to name just a few. The narrative unfurls during twenty-six very quiet weeks, on a very quiet country lane, in a very quiet part of Dorset. There is a strong sense of place explored through our daily walks and contact with the natural world. Unbeknownst to us, all through those gruelling months, Little Toller were four miles away, suffering their own lockdown in a neighbouring village. Our meeting seemed meant to be. It was a beautiful moment of serendipity and they decided to give our story a voice. Little Toller, in turn, sold the North American rights to Greystone, convinced that the united passions would serve well to launch the book in the USA and Canada.

I’m sure readers will be eager for reassurance that Reuben is still doing well. Can you tell us a little about his life now?

This book has given Reuben his voice back and helped him to gain a foothold in this weird and wonderful world. His obvious pride and renewed confidence are palpable to anyone who meets him. I have got my brother back! He still lives in the same flat in North Dorset and although there have been issues with his care (and doubtless always will be), he is in a much stronger place. To witness the return of his smile has been the greatest privilege of my life.

Rebecca Foster