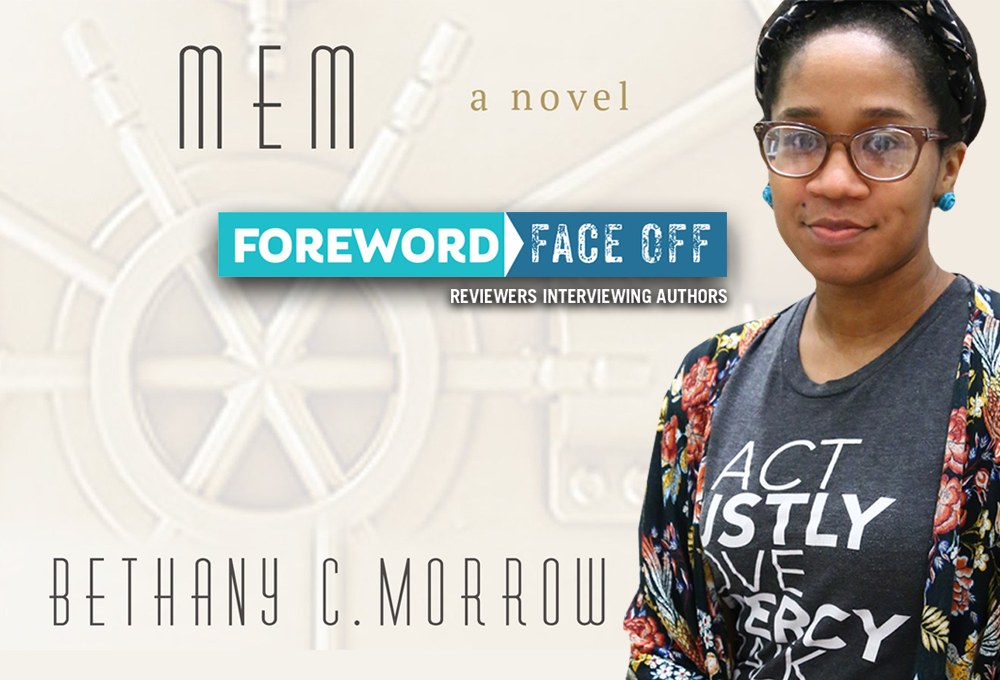

Interview with MEM Author Bethany Morrow

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers Explores Sci-Fi and Speculative Fiction with Bethany Morrow, Novelist of MEM.

If you like your fiction buttoned-up and linear, get out your ten-foot pole—Bethany Morrow is not your kind of novelist. Her new work of speculative-fiction, MEM, goes down dizzying paths of ethics, science, race, period setting, duality, and you just may need a bracing cold shower to get your bearings back.

But read it you must, if the written word matters to you.

In her starred Foreword review of MEM, Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers writes: “Morrow touches on science in order to further explore humanity. Memory extraction science borrows the language of banking, which only emphasizes the issues of class and privilege at play. … Morrow delivers a new classic in her exploration of identity, memory, and human property, proving that, like experience itself, memory is slippery, unpredictable, and rarely what it seems.”

In all of her many reviews for Foreword, we can’t remember her ever using that lofty word “classic,” so we knew this book and Bethany were prime Face Off interview candidates.

For U.S. readers, New York City is a familiar, habituated site in the literary imagination, so setting a story in NYC means the cultural consciousness does a lot of the work; the story can rely on a certain cultural shorthand. You also chose a major city, Montreal, when situating your novel. For non-Canadian readers who might not be familiar with Montreal, is there anything about the city—it’s history, demographics, etc.—that particularly inform your story?

Elsie (Dolores Extract No. 1) experiences quite a few historical events in Montreal, from the first fatal automobile accident to the opening of such landmarks as the Rialto Theatre, and so, of course, I’d have to say that the city’s history, and its expanding skyline informs the story to some extent. As well, Montreal is a place where the world sort of descends, with a diverse and ever-fluctuating population from all over the world, and you see that in the characters, from the primary to the patrons of the Professor’s extraction practice.

I’d like to delve into the issue of your alternate timeline. MEM takes place in the early 1900s, mainly in the 1920s. What made you choose the past—and this decade in particular—as the site for your science fiction?

From the first time I envisioned Elsie, she was wearing a cloche hat, and I was focusing on the art deco architecture that makes Montreal so beautiful to me, so in that sense it happens very organically. But once I fully understood who she was, and why, and I began researching historical events on the island that might enrich her story, I stumbled upon the British North America Act of 1867, in which it was written that women were not persons in matters of rights and privileges—and that that was not overturned until 1929, when the Famous 5, a group of Canadian women activists, appealed in what became known as the “Persons Case.” Therefore, I wanted Elsie’s story to resolve before 1929, and, though this was all head canon, I decided to write the story as though the original restriction had been in reference to Mems, but, of course, I didn’t want to diminish the real-life significance by overtly declaring that in the text.

There’s another, more selfish reason for the time period, even if I only realized it with the benefit of hindsight: I loved Montreal, and knew I wanted to write a sort of love letter to my then-adopted city, and I felt much less self-conscious setting it in the past where my opinion as an expatriate might not be as scrutinized!

Although MEM takes place in an alternate historical past from ours, I couldn’t help but read it as a more of a cautionary tale than a “gee whiz” story of imagination and human potential. What anxieties were you trying to unpack about modern life or our historical past, despite MEM’s alternate timeline?

When I wrote MEM, I was writing Elsie’s story, following a “what if” that was compelling to me and true to her. It’s really only in retrospect that I can see what I subconsciously might have been unpacking, and also through hearing the insight of other people, if that makes sense.

I’m confused by the desire to avoid or deny heartache and distress, and not in the context of abuse or toxic relationships, which are unacceptable and shouldn’t be embraced, but rather simply a refusal to experience even benign discomfort. I feel like my belated and then half-hearted attempts at Instagram stem from the fact that it’s one of the platforms that seems—in my very unimaginative use of it—to revolve around that: a kind of editing for appearance’s sake or even perhaps genuinely for the person in question. And this is no shade, I promise. I just think it’s an easy example of a larger issue. I think it becomes really clear in the novel that I have concerns about stripping away every instance of displeasure—and not because each instance has an inherent moral value, but simply because they occurred. In MEM, their existence in the Source, the person who has extracted them, is irreplaceable, and in some cases, their absence is, perhaps, fatal.

Throughout MEM, the main character, Delores Extract No. 1—who refers to herself as Elsie—is observing her world through a dual lens, both insider and outsider in different ways. What about this dual consciousness attracted you as a person and a storyteller?

This dual consciousness is my reality as a Black woman. A part of why I write is to create representation for myself and people like me, and to create perspective for everyone else, so I don’t think I’ll ever *not* write that dual consciousness, no matter what the world. It also happens to be the most compelling point from which to observe or compose any world.

In the story, there’s some pressure on Elsie to prove she’s autonomous by creating her own Mem. While Elsie seems to be against it, I couldn’t help but notice the chapter titles echoed the mem identification system, i.e., No. 1, No. 2, etc. Is there a greater significance to this title formatting?

The significance is that I liked it, lol. It reflected the world, for me, at the start of each chapter.

It seemed like women were disproportionately affected by the memory extraction process, both in how often women were the users/subjects of the science and in the wide range of women’s memories and experiences that were extracted compared to men’s. Nonetheless, this difference isn’t overt; rather, it builds through telling details across the text. What were you interrogating here?

I tend to believe that most atrocities and traumas disproportionately affect women, to be honest. There’s also a patriarchal element inherent to the memory extraction process, which is that men are deciding often what women can and cannot survive, so, really, the opinion of men is overrepresented in this world. Which, again, is my reality.

Science fiction often explores and speculates about the parts of our humanity we’re afraid of—the shadow sides. As such, it doesn’t usually traffic in happy endings, often preferring to reflect back the ways we have or could fail ourselves in irreparable ways. Yet, MEM gives its main character two gifts at the end: one interior and one exterior. That ending was such a surprise! Without giving too much away, could you discuss why that ending felt right to you and why you offered your main character reparations rather than stopping at the irreparable?

On one hand, perhaps, because as you said, science fiction lends itself to pessimism or negativity, I merely eliminate possibilities that seem too familiar when I’m writing. On the other hand, it very organically went in that direction for Elsie. She knew herself too well to not be able to put her finger on it at some point.

It’s interesting that you refer to it as reparations, and I honestly love that because then it’s a very easy question to answer. Elsie is a Black woman, as am I—why wouldn’t I offer her reparations? We know what the lack of it looks like; we’re familiar with the unending campaign of dehumanization and diminishing. What’s revolutionary is saying it doesn’t have to be this way.

As you say, Elsie is a Black woman. Because there’s interesting things going on with the Mems’ overall color/appearance during the story—most fading as they age while Elsie darkens—I found myself intrigued about the ways this might play with and change reflections and experiences of race, particularly for Elsie, and also for readers. How does this physical transformation relate to Elsie’s identity and self-discovery?

For me, of course, the physical transformation and the way it differs for Elsie is a rejection of colorism, of all the ways we’ve been taught that the acceptable Black woman—particularly in the wider, white world—is fair-skinned. Without putting that sort of nonsense into my work, I think it’s possible to reject it by the imagery I use, and the signs of Elsie being something remarkable, and that fact that her skin color and glow continues to deepen is very special to me.

How did you come to speculative fiction? Did it seem to be the right mode for telling this particular story, or do you consider speculative fiction your literary home?

Speculative fiction is my home. I would be very surprised if I were able to write a book-length work of fiction without it. It’s freeing, and not just to imagine things and places and concepts that have never been, but to respond to the world I know, without the burden of pedantry or heavy-handedness.

Letitia Montgomery-Rodgers