Interview with Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso and Amy-Jill Levine, Authors of Who Is My Neighbor?

We’re a fearful species, us humans. Even in this age of relative peace and prosperity, our fight or flight instinct is honed so keenly even unexpected loud noises cause us to jump out of our boots. Thankfully, we’re not often chased by tigers or ambushed by Neanderthals so the sudden shudder of terror is misplaced, a psychic remnant inherited from our hairier ancestors.

But the irrational fear surfaces in other situations. Take the general suspiciousness many of us feel toward people of different races and nationalities. That’s also deeply seated, and the strain of nationalism coursing through much of the world right now only serves to further dehumanize foreigners as “them people”—making it easier to rationalize withholding citizenship rights, financial support, and other kindnesses we extend to “our kind of people.”

With the help of saints like Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso and Amy-Jill Levine, we can do better. The authors of many enlightened titles for kids and adults, Sandy and Amy-Jill recently worked with Flyaway Books to create the immensely important children’s picture book, Who Is My Neighbor?—a “timeless tale of kindness, compassion, and what it means to be a good neighbor,” in the words of Pallas McCorquodale, in her starred review for the January/February issue of Foreword Reviews.

In preparation for this Face Off interview, Pallas leaned on Addison, Izer, Rozalyn, and a few other pre-teen students in her library to come up with some thoughtful questions for Sandy and Amy-Jill, a professor at Vanderbilt’s Divinity School.

Most importantly, please share this conversation with parents, teachers, and anyone else in positions of influence over youngsters, and encourage them to buy a copy of Who Is My Neighbor? What could be more important than raising tolerant, respectful, curious, and loving children?

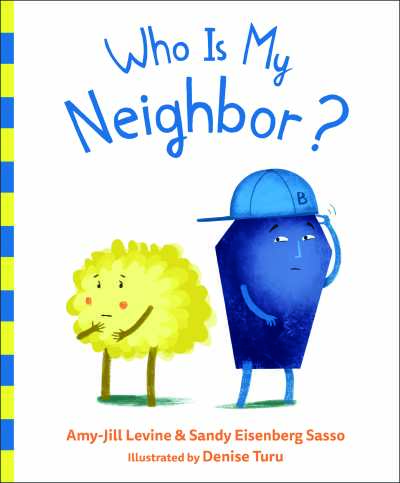

The colors make me think about how people are different colors, too, but we can still be friends. Were you thinking about all the different colors people are when you made Blue and Yellow? —Addison, age 12

Thank you, Addison, for your great question. We were thinking about all the differences that make human beings so interesting. We come in different colors, and we come from different parts of the globe. We have different religions, holidays, foods, and clothes. But we all have dreams and hopes; we all want to be safe and loved.

Why did you use colors instead of shapes or sizes to separate the characters? —Hannah, age 11

Hanna, thank you for this question. We thought colors would be the easiest way for people to see both the similarities and the differences between the characters. We could then have the characters be of different shapes and sizes: skinny and husky, short and tall, wearing glasses or riding in a wheelchair.

Why did you choose those particular colors? Are they your favorite colors? —Amanda, age 10

Thanks, Amanda. Actually, my (Amy-Jill’s) favorite color is red. I (Sandy) really like blue. We chose blue and yellow for a few reasons. First, Amy-Jill has a friend who has a medical condition called “red-green color deficiency.” That means he has a hard time seeing the colors red and green, and we wanted him to enjoy the book. Second, the color blue often means sad and the color yellow often means afraid. The Blues and Yellows are both afraid to be together and sad that they couldn’t be friends. Third, we like using puns, like “true blue” to mean both blue in color and faithful, and “good as gold” to mean gold in color and reliable.

Why don’t the Yellows and Blues like each other in the beginning of the story? Did something happen? —Rozalyn, age 10

Thanks, Rozalyn. We were hoping that people would ask this question. Yes, something happened, but it happened so long ago that the Blues and Yellows couldn’t remember what it was. All they knew is that their grandparents and parents told them how terrible the people from the other color were and those people should not be trusted.

Whenever we hear that a particular group of people is “bad,” we should always question that claim. If one person does something wrong, we shouldn’t assume that all the people in that person’s group are the same. We should not blame a group for the actions of one person.

Different groups of people, over time and across the globe, have not liked each other. If we could get to know people who are different from us, we might find out that we are more alike than different. We might learn to celebrate differences.

Are you friends in real life? Do you ever get mad or upset if you don’t agree on something? That happened to me with a group project once. —Iver, age 11

Thanks for your question, Iver. Our next book is actually about disagreements that come about because of a group project! Yes, we are friends in real life, but we live in different cities (Sandy lives in Indianapolis, Indiana, and Amy-Jill lives in Nashville, Tennessee). Therefore, we don’t get to see each other very often. We talk a lot by email—sometimes up to twenty times a day.

We haven’t gotten angry; that’s probably because not only do we like each other, we also respect each other. It might be harder to avoid difficulties with a group project, especially if you have to do the project because a teacher assigned it. Try letting people know how you feel and listen to how others feel. Maybe a teacher can help. We (Sandy and Amy-Jill) wanted to write these books. When we disagreed, we talked so we could better understand each other. That helped us write the very best story we knew how to write.

This is your third picture book collaboration, a concept that fascinates a lot of students. Can you offer a word of advice about teamwork?

Remember to be patient and to recognize the different gifts of the people with whom you are working. (For example, Sandy knows how to write for children and Amy-Jill knows the primary sources on which our stories are based.) It is important to listen, really listen, to each other. You should be open to another person’s idea and take it seriously. Respect each other. Never make fun of what someone else suggests. Sometimes it is okay to compromise. Make sure everyone feels included.

Biblical themes are a common thread in your children’s books, both The Marvelous Mustard Seed and Who Counts? are also based on parables. How much does your personal religion or faith influence your writing?

The primary reason we had for writing children’s books about the parables is that often these parables are taught in anti-Jewish ways. The parents and teachers who read the texts anti-Jewishly are not bigots; the problem is the misinformation they were given about Jesus’s Jewish context. Then they unknowingly pass this misinformation along to children.

The parables are not about attending a worship service, believing in a particular creed or doctrine, or even suggesting a higher power. Many of Jesus’s parables, and many rabbinic parables as well, are stories that teach us how to act with others and in the world.

Food is a key point in bonding the Blues and Yellows and is mentioned several times—blueberries and blue cheese or butterscotch cookies and bananas. Is there a cultural or biblical significance to diets or sharing food?

All cultures have special foods. In America we eat turkey on Thanksgiving and hot dogs on the Fourth of July. We also associate foods with certain cultures: spaghetti suggests Italy, dim sum suggests China, wiener schnitzel suggests Germany, kitfo suggests Ethiopia, and so on. Sometimes we are afraid to try different foods because they are so unlike what we are used to eating. But when we do taste new foods, we often are surprised to learn how good they are.

Based on the endnote, the parable of the good Samaritan seems like a weighty subject for children to tackle with nuances from a historical, social, and even linguistic perspective, yet there is also lightheartedness and humor in your version. Was it challenging to find a balance between fun and thoughtful?

Parables, most of the time, are both ethical and entertaining. Amy-Jill’s Short Stories by Jesus: The Enigmatic Parables of a Controversial Rabbi (HarperOne, 2014) shows how Jewish authors in antiquity frequently used humor in order to convey moral teaching. All of Sandy’s children’s books are celebrated for being both engaging and instructive. We think that children’s books should be both interesting and enjoyable.

Scripture isn’t mentioned during the actual story, appearing only as a final note or explanation for adults. Sample questions are also included for suggested guided readings. Did you envision Who Is My Neighbor? being utilized as a supplemental tool or in conjunction with a larger lesson plan rather than a standalone story?

We do not mention Scripture in any of the parable books for children. If parents and teachers want to include the original context of the parables (they are found in the Gospels in the New Testament), they are welcome to do so. The books stand alone, but we think it would be great if libraries, and parents, gave children access to the full series. Sometimes people won’t read a story because it is not from their tradition. But good stories are good for everyone. We hope Who Is My Neighbor? will be enjoyed by everyone.

In 2018, Abingdon Press has produced a six-week study guide (video, leader guide, participant guide) on the parables, based on Amy-Jill’s book. We also think it would be great if parents and children could read the same parable—the adult version and our book—and then talk together about it.

Pallas McCorquodale