Islam Issa Talks About Alexandria: The City That Changed the World

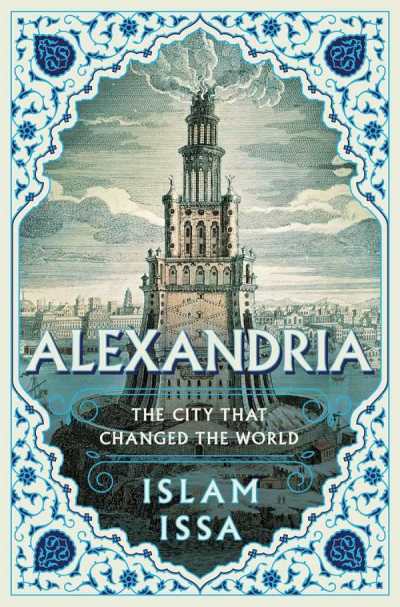

Today’s interview takes us to Alexandria, and all of you librarians instantly think of the Great Library of Alexandria, which was established around the 3rd century BCE by Ptolemy I to hold all the world’s accumulated knowledge—it held five hundred thousand books and texts in several languages, as well as Aristotle’s works and original manuscripts by Greek dramatists.

And then, in the 1st century BCE, the Great Library went up in flames, an unfathomable act of destruction long blamed on, you guessed it, Arabs. More recent scholarship, including by Alexandria’s greatest Classical historian, Mostafa el-Abbadi, points the finger at Julius Caesar.

It took until 2002 for Alexandria to replace the Great Library with Bibliotheca Alexandrina, a $220 million architectural marvel with a 220,000-square-foot reading room, four museums, a planetarium, galleries, a conference center, and gift shops. To many, the new building revitalized the intellectual culture of what used to be Egypt’s ancient capital city.

Onward: check out Jeff Fleischer’s Foreword review of Islam Issa’s Alexandria: The City That Changed the World, and enjoy the interview.

How did you become interested in the idea of writing what’s in many ways a biography of a city? How did you decide what approach to take?

Alexandria has always been an important part of me and I grew up hearing stories about so many different periods and figures related to the city. The idea of collating these into a complete history actually came during the pandemic; I was living in Scotland and very much missing Egypt, so it was a way of reconnecting with the city of my ancestors.

Spatiality is really important to me and there’s so much to be said about the way in which culture, including mythology, plays a role in the creation of places and the forging of the societies that dwell in them. Culture then continues to serve as a catalyst for the way we imagine and conceptualize a place. So in terms of approach there was definitely a strong sense of cultural history. I wanted to give the founding myths and various legends as much attention as the historical dates and figures in order to build a complete picture of Alexandria, because it really is a place that blurs the lines between the factual and the mythological, and where the early visions of Alexander the Great and his successors have constantly permeated the city’s long history. So it also made sense to take a roughly chronological approach, which I interspersed with my own experiences of present-day Alexandria.

What was your favorite time period or subject to write about in Alexandria, and why?

It’s hard to pick one! The subject of the Great Library is pretty exciting, especially how obsessed the Ptolemies became with gathering all of the world’s books and the policies they put in place to do so, like searching incoming ships for books and banning the export of papyrus. The famous Cleopatra is actually Cleopatra VII, so each of the six preceding Cleopatras has an intriguing story, too, brimming with political theatre. I liked seeing characters and their psychologies in a different light through the lens of Alexandria, like Alexander the Great, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Saladin. And in some ways, the unsung hero of the book might just be my grandad, so delving into his life and trying to figure out what he thought of the various events of the twentieth century—independence from Britain, the toppling of the Egyptian monarchy, and of course several wars—was one of the most striking aspects of the writing process.

What was the research process like when creating the book? How did you approach covering so much history in one volume?

Right at the start, I came up with a rough structure and the chapter list actually ended up almost exactly as I’d envisioned. I knew that there were essential figures, events, and dynasties that needed to be covered. Although there were some underlying threads throughout, I researched each chapter as its own product and wrote chronologically, too. I wanted to be sure that I could feel the passage of time.

I began by reading the ancient histories and classical accounts, which included biographies, anthologies, and mythologies. I often needed to look at modern research, especially in fields where I had much to learn; these ranged from archaeology to zoology. There were also religious scriptures and folk tales. But really it was about adapting to whatever was needed: the details I sought could be anywhere, from poetry to travel writings to CIA records! And of course the time I spent in Alexandria was vital. I visited sites, museums, and galleries. I went to archives with the intention of being surprised and ended up buried in manuscripts, reports, letters, images, and maps. I spoke to family members, especially older ones. And I had conversations with anyone who wanted to talk, from friendly strangers in cafes to eccentric vagabonds in alleyways; I must have listened to half a dozen theories about where Alexander is buried! And honestly, the atmospheric research, just walking around the city—a flaneur, if you like—was so important because I wanted to bring the city to life, which isn’t possible if you’re a complete outsider or if you’re content with sitting in a library.

What surprised you most about the history of the city as you researched the book?

I was taken aback by the way that history is constantly repeating itself, albeit in slightly different ways. Another surprise was how some things just seemingly vanished, like the mausoleum of Alexander the Great which the Roman emperors make a point of visiting one after another, then all of a sudden a note at the turn of the fifth century tells us that “his tomb even his own people know not.” As for specific surprises, there were a few archival finds that struck me. I won’t give them all away, or their exact details, but one is a letter during an eleventh-century famine that reveals cannibalism. Another is a poem about Alexander the Great by the early Muslims of the city; mine is the first English translation of the poem and it speaks to the founder’s importance through the various eras.

The level of detail in the ancient world chapters, such as describing the creation of the library, is impressive. What were the keys to achieving that kind of narrative detail?

The detail really is a synthesis of so many different sources and ideas. Often, the details would be hiding in the most unexpected places. For instance, there’s a Byzantine poem that quotes the second librarian saying there are half a million scrolls in the Great Library! Another fascinating example is the first-century Wars of the Jews by the historian Josephus; it’s primarily a Jewish history, but hidden in this seven-volume work is a speech by a Herodian king that states Alexandria’s size in furlongs and is actually the most detailed and useful note about the ancient city’s size!

How did working on Alexandria change your relationship to the city or how you think about it?

Alexandria has always been close to my heart; writing Alexandria has made it even closer. I’d say that the book changed my relationship with my predecessors; by the end it all felt quite personal. While writing, I was struck by the fact that my father’s ancestry test returned 97.5 percent next to the word “Alexandria.” So I tried to search for Ancestor the Great— the first ancestor to venture to this part of the world—and although ultimately I couldn’t locate them, I now feel a more intergenerational connection with the city. It’s also humbling to see that our present is but a minor part of a substantial timeline. And more tangibly, although much of the history isn’t physically present anymore—lots of it is under the ground and in the depths of the sea—wherever I go in Alexandria, I am definitely reminded of historical events and figures in a way that I wasn’t before. All of that history, all the ups and downs and love and hate, took place in this single space.

Jeff Fleischer