It's Reading, Writing, and Renaissance: Picture Books in Today’s Classrooms

He was seven years old, fringy black hair, newly toothless, and brown eyes that sparkled. His teacher asked if he could have an impromptu meeting with me during a day of author presentations, saying she had never met a more impassioned, imaginative young writer, particularly given the challenges he faced learning English as his second language.

I kneeled, and asked what he’d been writing lately, or was dreaming about writing. Then I listened and rode the vibrating, tangent-filled story train with him, awash with gratitude for teachers like his who recognize, affirm, and shape these story writers, and for kids who thrill with their own power to create. I expect to pull his books from the library shelves one day. He expects that too.

This is an ode to the teachers, and the leaders of teachers, who harness picture books as literary workhorses in their classrooms. While some books are gulped in a single reading session, many others are studied, dissected, and held up as mentor texts to teach specific writing craft moves, modeling for children skills they can experiment with in their own stories.

Beyond teachable examples of writing craft, the bar has been set high for children’s book authors and illustrators to create picture books with meaningful discussion points that help support character building programs in the schools, spur social action, or lend themselves well to children fully engaging in extension activities that springboard from the text.

When our youngest son was a newborn, his kindergarten sister wanted to hold him. Wrapped and swaddled, we laid her brother in her lap, but she protested his bundling. “I want to FEEL him.”

That’s what’s happening in so many schools—this hunger for picture books as an experience, to be felt, tried on, reread, and remembered. And this enthusiasm creates an exciting but delicate renaissance for writers and illustrators.

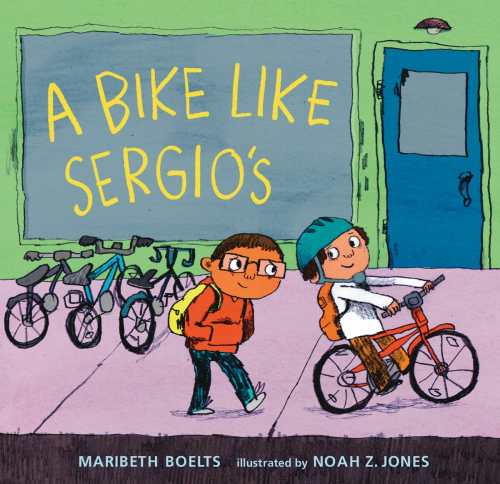

Case in point. A masterful third grade teacher recently blogged about reading my latest book, A Bike Like Sergio’s (Candlewick Press) to her students. In it, Ruben feels like he is the only kid without a bike. His friend Sergio reminds him that his birthday is coming, but Ruben knows that the kinds of birthday gifts he and Sergio receive are economically different. When a woman drops a dollar bill, Ruben picks it up, and decides to keep it. At home, he discovers it is not one dollar or five or ten—it’s one hundred dollars! Will he return the money? Tell his parents? Lie about the money’s origin and buy the bike?

The book was shared, and upon hearing the ending, (spoiler alert) where Ruben returns the money and doesn’t get his bike, the third graders were aghast.

“That’s the worst ending ever!”

“There has to be a sequel!”

Gulp.

The teacher listened to all their strong feels, and proceeded to share and talk about two more of my books, Those Shoes and Happy Like Soccer. Throughout the week, they studied and charted the themes, endings, similarities, and differences. And they made some astute observations.

Finally, A Bike Like Sergio’s was reread, but this time, with a deeper understanding of the story, plus additional context from the other two books. It was then they concluded that Ruben’s tale truly DID have a happy ending, bike or not. Whew!

This type of in-depth analysis and application carries with it a whispery thread of caution for writers. The picture book, with all its mystery and magic, must continue to be written for its own sake, free of the practical mindfulness about how or even if it will be used in the schools.

Because children can sniff out a “good for me” book in the same way they sense the bran snuck into the pancakes. They know it’s in there. They do.

We as writers know too. Suddenly, we’re self-conscious, deliberate, or prescriptive, tuning out our characters and their unfolding stories, as well as our own inner 8-year-olds who want to be dazzled, who want to pretend and laugh and do brave things, and who want, more than anything, to make sense of themselves and the wild world around them.

But within the source of the tension may also be its cure. Again, at school. Again, with stories.

A young Hmong student loved to write poetry. When a teacher visited her home, instead of artwork or photos adorning the walls, her proud parents had displayed all of her new-to-English poems.

Another student, introverted and shy, wrote a beautiful story but was petrified to read it aloud at an assembly. A teacher asked if she’d consider reading it to an audience of one, while she videotaped it, and the girl agreed. The video was shown instead, with the student’s temperament honored, and her gift affirmed.

And then, a reminder just last week from a child in a New Jersey school. Within ten minutes of my arrival, a long-lashed, earnest, first grade boy handed me his story, complete with illustration. It was about a blue star and a red star, and how at first they didn’t get along, but then did. So well that they cooked a turkey together! I thanked him and he skipped off, leaving me touched by how unencumbered writing can be, when we trust the bubbling up of the story, and hush thoughts of any future usefulness or potential impact.

So, thank you, teachers. Thank you for creating your story rich classrooms, and for extracting precious time and space in busy school days for shaping writers. Thank you for author’s chairs, classroom publishing, writing assemblies, writer’s notebooks, and poetry read over the intercom after the Pledge of Allegiance.

And thank you for guiding your students to turn to books, just as authors do, when the world looks scary, piques curiosity, or asks for an enlarged and hopefully more empathetic perspective.

When our stories are lucky enough to find a home in your hands, and with your young writers, it’s the happiest of endings.

Maribeth Boelts is the author of numerous books for children, including Those Shoes, a previous collaboration with artist Noah Z. Jones, and Happy Like Soccer, illustrated by Lauren Castillo. She lives with her family in Cedar Falls, Iowa.

Maribeth Boelts