It's time to normalize this

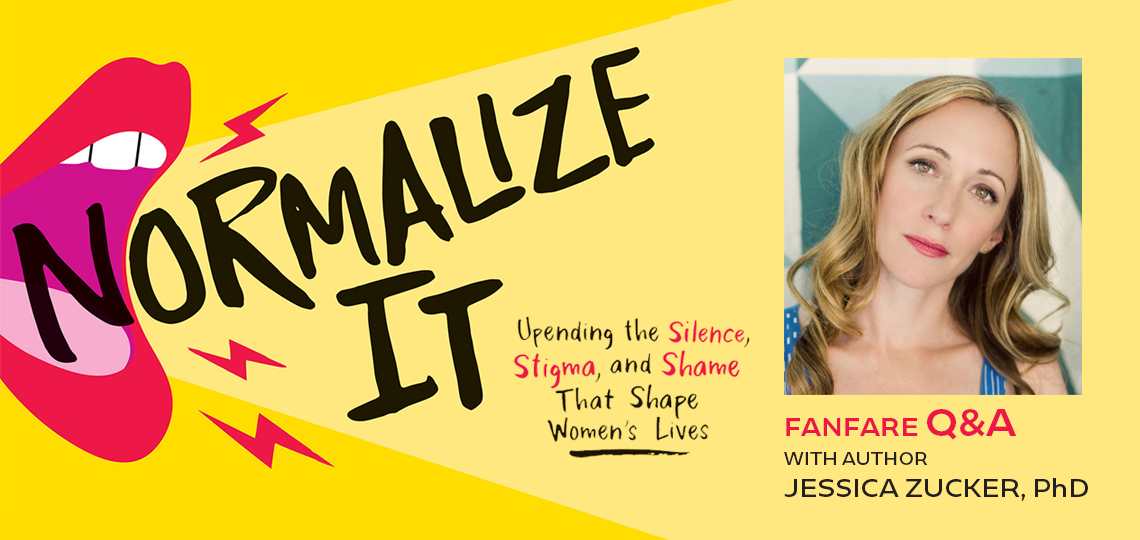

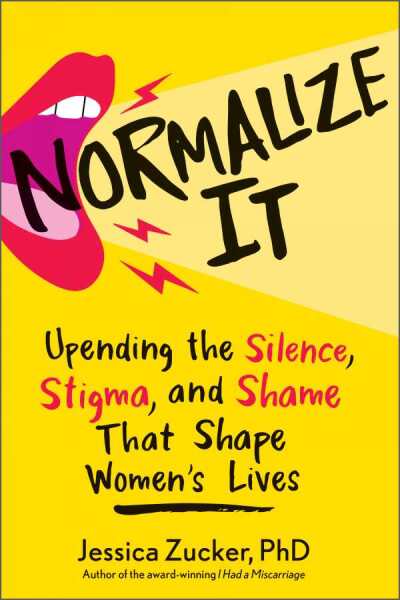

Reviewer Sarah White Interviews Jessica Zucker, Author of Normalize It: Upending the Silence, Stigma, and Shame That Shape Women’s Lives

Clinical psychologist and author Dr. Jessica Zucker has a dream: That one day all of us will view “vulnerability not as something scary but as a strength that will literally change our world.” She led the charge with her unflinching and raw memoir, I Had a Miscarriage (Feminist Press, 2021), and subsequent social media movement, embracing storytelling and the sharing of vulnerabilities over silence, stigma, and shame.

With the April 22nd release of her new book, Normalize It, just around the corner, Jessica is with us today to talk about the harm that is caused by staying silent and the benefits of sharing the truth about difficult and traumatic experiences. Silence festers and “can deepen the pre-existing pain that often morphs into shame,” she says in the interview with Sarah White below. “Opening up begins to let the light in.”

In her review for Foreword‘s March/April issue, Sarah White writes, “Normalize It demonstrates that storytelling is the way to break the cycles of silence, stigma, and shame that keep women from disclosing difficult episodes in their lives.” We’re excited to help Jessica bring that message to the world.

The book makes clear that women sharing their stories is key to making these common life events seem as normal as they are. But a big part of sharing stories is allowing yourself to be vulnerable. How can people get more comfortable with being vulnerable enough to share their stories?

Sharing our stories is hard, especially when they’re caught up in the trifecta of silence, stigma, and shame. I always offer my patients—and readers—this truth: You don’t have to open up if you don’t want to. You don’t owe your story to anyone, and you should never feel pressured to share something before you feel ready, or in a setting that triggers alarm bells in your head.

But I also offer another truth: sharing our stories can open us up to deeper connections, less mental anguish, and a lighter sense of being. When you are ready.

Working up the courage to get vulnerable in this way usually starts with exploring what you are losing by staying silent. Is not talking about the hard stuff creating distance between you and a loved one? Or preventing you from feeling truly seen in your relationship, among friends, by your community? In my personal and professional experience, silence festers. Silence can deepen the pre-existing pain that often morphs into shame. Silence makes us feel alone. Opening up begins to let the light in.

When you feel ready to share your story, I recommend starting with someone you trust—because there is a sacred vulnerability inherent in talking about taboos. This is where working with a therapist who is trained to sit with your vulnerability can be really helpful as a start.

Why is working with a therapist an important part of the process?

Intimate conversations like the ones that take place with a trained mental health professional are among the most essential ways we can address stigma and shame in our own lives.

Therapy offers a space to unpack feelings fully, understand the roots of those feelings, and feel seen and understood. We can learn to trust ourselves more fully as well, as we begin to connect the dots between the things we’ve lived through and who we are today. Much of my job as a psychologist is to help my patients feel seen and validated, and to help them understand their histories and the stories that have shaped them. The relationship between patient and therapist has the potential to breathe new life into childhood, adolescent, and adult memories that are frequently left unexplored. Along with the therapist’s extensive training and knowledge of various ways of working with patients is the promise that a consistent therapeutic relationship can, in and of itself, allow for meaningful psychological repair. Talking with a trained professional can literally change your brain chemistry in a process called neuroplasticity, by which experiences and feelings influence the actual structure and functional ability of the brain.

Therapy gently allows people to see that their lived experiences have sometimes colored their view of themselves, their relationships, and their ability to trust in what they believe about who they are.

By beginning this work with the support of a therapist, you can determine whether or not you feel safe in talking about the hard things in other spaces, how and when to share your story if you chose to do so with others, and process any reactions that feel harmful or disappointing.

Social media is often blamed for a lot of our issues with comparison and assuming everyone has their life much more together than we do. But it can also be a way to share stories more widely and learn that we are not alone in our problems. Any tips for using social media in an empowering way?

I’ll preface this by saying I don’t think that you have to blast your experiences and the complex feelings that surround them on social media in order to find healing. Many of the women in this book would have found the idea of sharing their miscarriage publicly the way I did, for example, totally overwhelming. And that’s completely okay. The idea of sharing our stories, especially the hard ones, can sometimes feel like an all-or-nothing decision. Either you tell no one, or you tell everyone.

You can absolutely find empowerment and peace by sharing your story with just one person, or with a select group of people in other ways, offline.

That said, many women, including some featured in these pages, did and do find liberation by sharing their stories with their online communities. This isn’t a better or worse form of storytelling, they were simply ready for a more public conversation.

The first thing I would advise is taking a moment to pause and reflect. Imagine yourself hitting “share.” What do you feel? Nervous but exhilarated? Or scared and filled with anxiety that your boss might see it? Ask yourself what you hope to gain or achieve from sharing with an online audience. Do you feel the need to get something off your chest? Hope to start a bigger conversation? Want to help others feel seen? A therapist can be really helpful in this process, helping you game out different scenarios and process the responses.

You also get to decide how you might like to share. There are lots of ways to manage your privacy, for example. I often see women find solace in private groups on social media where there’s more of a sense that everyone in the group has opted into these conversations. There’s a higher expectation of empathy and confidentiality. Similarly, sharing with a list of only close friends on social media can help take some of the risk out of sharing something personal more broadly.

You might even find that simply drafting a post helps ease anxiety or makes you feel less isolated. Putting feelings into words rather than keeping them bottled up literally changes the way the brain responds to stress, diminishing activity in the amygdala, the part of the brain that processes emotions like anxiety, fear, and stress. Whether or not you ultimately hit “share” is up to you.

How can we support friends or people we encounter online when they share these kinds of stories? Is there a “right” reaction?

Culturally, we have a tendency to respond to others’ pain with what I call the “at least” trap. At least it wasn’t worse. At least you can try again. At least you’re not alone. Platitudes gone awry. These statements are typically well-intentioned (most of the time) but they can end up deeply undermining the legitimacy of a traumatic experience. They shut down the conversation, essentially urging the person sharing to get past the messy stage and on to polishing away the jagged edges of their pain.

A better reaction—whether to a story shared online or with you directly—is to simply be present. Share that you are here to listen, check in periodically and ask them how they are doing. Don’t try to make them feel better by hurrying the grief along—simply sit with them in the whiplash of it all.

How can society as a whole make it easier for people to share their stories?

It’s my hope that we see the shift from “at least …” to “I’m listening …” happen on a broad scale. But that starts with the individual. That’s why I wrote this book—to challenge all of us to see vulnerability not as something scary but as a strength that will literally change our world. It is a revolutionary idea: to create a culture that encourages storytelling over silence.

Your work and the book focus on difficult events in women’s lives, but a lot of these issues touch men’s lives, too, and men are often asked to be stoic and not share their feelings and stories. Do you think the antidote is the same for men? How do we encourage them to share their stories too?

Yes! I believe that the power of talking about the hard stuff, sharing our stories in community, in therapy, and in our relationships is revolutionary. For everyone.

With men, the cultural pressure to be silent around taboo topics is arguably even stronger in some respects. And while they face many of their own unique “shoulds,” many of the stigmas that dog us are the same: body image, insecurity, perfectionism, loss, grief, aging. Men are taught not to utter these things out loud, let alone even feel them quietly.

But as I hope comes through in the book, this process of sharing our stories should be an authentic one; there is no one-size-fits-all approach. The book is not a prescriptive set of steps for how to begin normalizing the things we feel ashamed about the “right” way. Rather, it’s a call to action that I hope inspires anyone feeling strangled by stigma or taboos to envision the future that waits for us on the other side of silence.

The book is sure to inspire readers to think about their own stories and how they might best share them and with whom. What’s a good next step after reading the book for those who want to tell their own stories?

The first step is the simplest one: just say it. When you’re alone and someplace you feel safe, verbalize the shame. Put words to what you think is supposed to remain hush hush. Or, if you’re someone who journals, write it down. Put pen to paper and let it flow. There is immense relief to be found in simply articulating the hard stuff, moving it out of your own head, and into the room with you. That in and of itself can be the start of a profound shift.

From there, I recommend inviting a mental health professional or someone deeply trusted in your life into the conversation. The more we speak up about our hardships, our struggles, and our pain, the sooner we usher in the change we need … and deserve.

Jessica Zucker is a Los Angeles-based psychologist specializing in reproductive health and the author of the award-winning book I Had a Miscarriage: A Memoir, a Movement. Jessica is the creator of the viral #IHadaMiscarriage campaign. Her writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, New York Magazine, Vogue, and Harvard Business Review, among others. She’s been featured on NPR, CNN, The Today Show, and Good Morning America, and earned advanced degrees from New York University and Harvard University. Her second book, Normalize It: Upending the Silence, Stigma, and Shame That Shape Women’s Lives, is out April 22nd.

Normalize It

Upending the Silence, Stigma, and Shame that Shape Women’s Lives

Jessica Zucker

PESI Publishing (Apr 22, 2025)

Jessica Zucker’s self-help book Normalize It demonstrates that storytelling is the way to break the cycles of silence, stigma, and shame that keep women from disclosing difficult episodes in their lives.

Zucker shares composite case studies of clients from her psychology practice, which focuses on reproductive and maternal mental health, to illustrate wider issues including grief, shame, pregnancy loss, sexual trauma, the complex feelings surrounding motherhood, and the pressure to be perfect. “Examining our stories is often the first step in accessing more freedom, authenticity and connection,” she writes, allowing people to “begin the process” of understanding and integrating their life experiences. It also helps to break taboos that keep women from sharing their stories and lets others know they aren’t alone.

Herein, women’s stories are combined with statistics and research to show how common these issues are. The book encourages working with a therapist to discover how, when, and to whom one’s personal episodes should be told. Because everyone’s experiences are different, it says, the best courses of action will vary. Still, plenty of options are named for those who have a story that needs sharing: revealing a truth on social media, disclosing to a family member, contributing to an online support group, or writing about the event are all recommended.

Most of the book’s stories are positive, focusing more on the beneficial effects of disclosing traumatic episodes than on the potential backlash. By exploring the normalcy of events that are often kept quiet, Zucker encourages acknowledgement of hidden truths and the consideration of how truths might be brought into the world.

Normalize It is a vital, supportive self-help book that encourages having illuminating discussions about one’s difficult life experiences.

Reviewed by Sarah White

March / April 2025

Sarah White