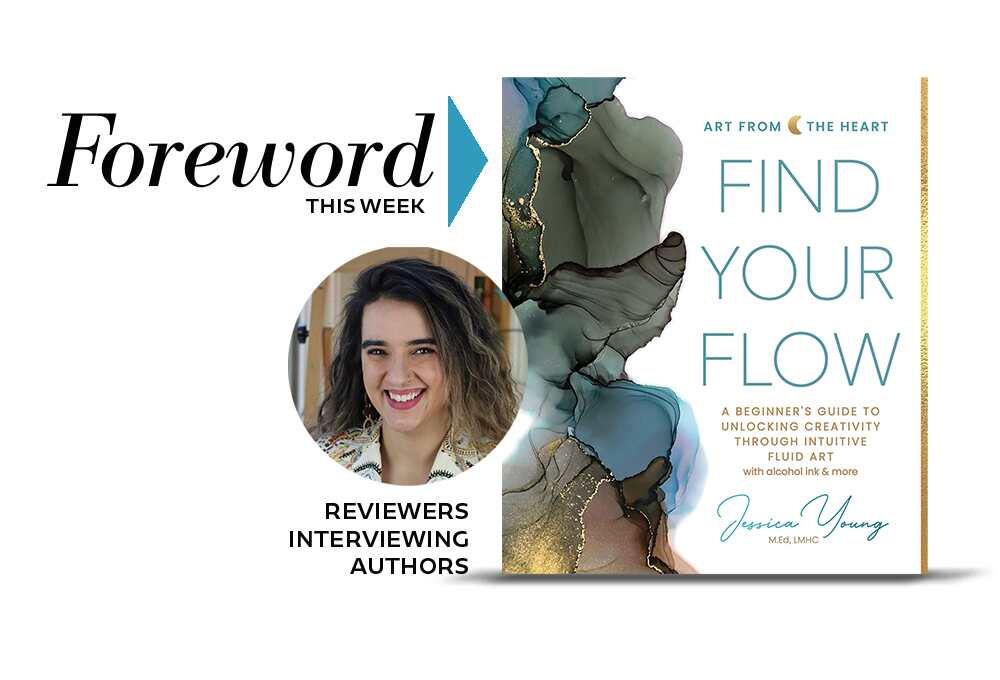

Jessica Young Discusses Find Your Flow, Her New Book on Unlocking Creativity through Intuitive Fluid Art

Trauma—once it pays a visit to the human psyche, it never leaves. Finally, science is beginning to understand why post-traumatic stress disorder is so debilitating.

A recent New York Times article describes the problem, and the progress, this way:

“Decades of treatment of military veterans and sexual assault survivors have left little doubt that traumatic memories function differently from other memories. A group of researchers at Yale University and the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai set out to find empirical evidence of those differences. The team conducted brain scans of 28 people with PTSD while they listened to recorded narrations of their own memories. Some of the recorded memories were neutral, some were simply ‘sad,’ and some were traumatic.

“The brain scans found clear differences … The people listening to the sad memories, which often involved the death of a family member, showed consistently high engagement of the hippocampus, part of the brain that organizes and contextualizes memories. When the same people listened to their traumatic memories—of sexual assaults, fires, school shootings and terrorist attacks—the hippocampus was not involved.

“‘What it tells us is that the brain is in a different state in the two memories,’ said Daniela Schiller, a neuroscientist at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and one of the authors of the study. … ‘The brain doesn’t look like it’s in a state of memory; it looks like it is a state of present experience.’ … The traumatic memories appeared to engage … the posterior cingulate cortex, or PCC, which is usually involved in internally directed thought, like introspection or daydreaming.”

In other words, “Traumatic memories are not remembered, they are relived and re-experienced,” says a PTSD expert from the University of Western Ontario, so as they pursue treatment options, “researchers should explore therapies, like mindfulness, which are known to activate the parts of the brain known to provide context.”

The PCC is also involved in the creative process, which brings us to today’s guest, psychotherapist Jessica Young, who encourages her traumatized clients to paint abstract art as a path to healing.

The author of Find Your Flow, Jessica agreed to take a few questions from reviewer Kristine Morris.

Find Your Flow is your first book, and it is visually stunning, insightful, and encouraging. What was your experience writing it? What came easily to you? What aspects were more difficult?

Thank you so much. Writing this art book was an interesting challenge because it required both my writing skills and my creative skills. Before I could write the actual manuscript, I had to develop and produce the projects for the book. On top of that, I photographed all of the projects and processes captured within its pages. I think the hardest part in developing the manuscript was coming up with unique projects that I knew hadn’t been seen anywhere else in the fluid art or alcohol ink community. There are many amazing artists out there that have beautiful books and materials on working with fluid mediums, but I felt I had something special to bring to the table that was unlike what I had seen so far. Before I could get into the nuts-and-bolts of writing the book, I had to make sure that these projects were perfect. I think that was the biggest challenge, together with photographing them almost entirely on my own. I didn’t have an assistant helping me (except for my wonderful husband at times), so on project days it was me and the eight “invented hands” I had to come up with to handle my remote controls, phone mount, camera mount, and the multiple devices I used to film and record the process. I felt like an octopus! But by the end of it I had a great rhythm going and was impressed with how efficiently I was able to multitask. Once the projects were completed and photographed, the manuscript felt much easier to write, and this confirmed my deep desire to write another book, perhaps one that’s more text-heavy.

You are an artist, a psychotherapist, an author, and also a practitioner of several healing modalities. What led you to combine the art-making process with healing in your own life, and then bring this potent combination out into the world to benefit others?

My family would tell you that I’ve always been an artsy person. I always loved art class and excelled at creative projects, but the perfectionist part of me always focused more on intellectual pursuits and academia. Art as a career was never an option, not a serious one anyway. I spent the earlier part of my life pursuing higher education degrees and securing my license to become a psychotherapist, which felt like the backbone of what I wanted to do with my future. I always knew I wanted to help people, but I never knew how much I needed to help myself before I could function as the type of clinician I wanted to be. When I was 25, at the height of my education and career, I suffered complete physical and emotional burnout that almost cost me everything. At that time the only thing that felt truly healing was creating. I was utilizing art to heal my own emotional struggles by teaching myself to paint, and at the same time I was incorporating more and more art-making in my clients’ therapy. I witnessed art open up deeply traumatized folks, I witnessed it give a language to humans who’d never had the words to express themselves, and I saw myself developing a clearer understanding of how I was showing up in the world as a healer through the art we were making. It seemed like the obvious and natural transition to begin developing an entire life and process around healing through intuitive art.

What are some of the changes/growth/awakenings you see in others as a result of including an art practice in their healing journey?

In my work as a therapist and mentor I have seen art-making provide a language to communicate what otherwise may never be said or known. When you learn how to create art with emotion, or even just view art with an appreciation for the emotion that went into creating it, you empower the creative healing process. Art-making has directly impacted my clients who have experienced trauma and/or deep emotional turmoil and given them a way to communicate what they’ve been through and how it’s impacting them without actually having to use words.

Words can feel extremely scary for traumatized folks or for people who are struggling with their emotions. Therapy clients who had been labeled as “resistant” by other therapists would invite me into their world through the art I prompted them to make. Hesitantly, they would put pen, paint brush, or crayon to paper and we would go on a slow and compassionate creative journey over the weeks that followed. Sometimes I would just sit and witness, with no words exchanged for the entire therapy hour. But they would emote through textures and colors and sometimes even the words they would write. When you throw out the fear of making bad art and just allow yourself to utilize art as a form of expression, you witness people open up in ways that will truly inspire you. I have seen struggling addicts put down their addiction in exchange for what they call an “addiction” to art-making. I have seen a little girl who was considered non-verbal tell me about her entire world just through the pictures she would draw for me. I have seen “criminals” choose the straight path forward in exchange for recognition of their disregarded talent. Art truly has the power to change the healing trajectory for people who are otherwise perceived as the most helpless, but only if we allow it to.

Please explain what is meant by “intuitive” art, and why it is such a powerful ally in self-care.

Intuitive art has many definitions, and every intuitive artist will tell you something different about how they identify with its meaning. Personally, I am drawn to intuitive painting because I am a self-taught artist who truly paints from intuition—I am not sourcing my inspiration from a set of pre-defined skills or a pre-defined talent. Intuitive art allows for mistakes, it isn’t necessarily defined by a specific style or medium, and it’s not defined by a traditional definition of what art is or is not. It allows you the freedom to truly express what is inside of you rather than what is expected of you. Intuitive art is guided by the heart, the gut, and by what you’re feeling in the moment; you’re allowed to create whatever your intuition guides you to create, and that’s the most beautiful part of it. I also find there is less gatekeeping amongst intuitive artists since it is such a personal process, and I enjoy the freedom in that.

What does “flow” feel like to you, and how has experiencing the flow state enhanced your life?

I’ve spent a lot of time in my life not fully present in the moment. I’ve spent a lot of time counting down the minutes till the next minute and anxiously anticipating the future. I’ve also spent a lot of time stuck in the past, usually trying to figure it out or fix it. Art, especially intuitive fluid art, allowed me to access a place where I was no longer stuck in the future or in the past, or stuck feeling bored about what was or wasn’t happening in the present. Flow, for me, is spending hours and hours and hours barely thinking about anything other than what I’m doing in the moment. As an anxious person, and one who is always worrying about the next day or the last thing, the flow state feels like a release from it all. As someone who has been working to regulate a chronically dysregulated nervous system all her life, flow state is the state of equilibrium my body has always longed for.

Why is creating abstract, fluid, intuitive art an especially good way for people to experience their own “flow state”?

Because it is so freeing and limitless. There is no end to what you can create, and you can spend countless hours entranced by the effects of combining different mediums. It is a science, a meditation, and an art all in one.

You take a “process-over-outcome” approach to art-making. In our results-oriented culture, what can help us make the shift from a results-oriented approach to full immersion in the process and pleasure of art-making?

More mindfulness and present moment awareness, less idealization of what makes worthy art. More creating for the sake of creating rather than trying to impress people. I think social media has definitely put a damper on the “process-over-outcome” approach because we are always trying to create the next best thing, keep up with the next best thing, and struggling to get our work seen by as many people as possible.

I think there’s something special about the “old days” before everything had to be shared on social media—the days when you could have a private, sacred art practice that made time for things like flow and experimentation. I think the most fulfilled artists still keep this part of the practice as foundational. Slowing down our pace and relaxing our drive to be seen and accepted by others will help us go more deeply into what it is that we want to create, rather than what we feel like we should be creating. We also need to accept that making bad and ugly art is a fundamental part of the process, and is in no way an indication of regression or stagnation. It’s what we do with the bad art that matters, not that we create bad art in the first place.

How is interacting with abstract art different from viewing representational art? What changes in expectations and/or mindset might be required of the viewer to appreciate abstract works?

For abstract art, you have to have a connection to the deeper meaning of what is tangible and seen by the naked eye—you have to be willing to think beyond what you see or know. I think people who harshly criticize abstract art may struggle with imagination. If you struggle with make-believe, then it might be hard to see the tree in the scribbles or the woman with the flowing hair in the flowing ink. But if you grew up creating imaginary worlds out of your own thoughts, then it may not be so difficult to appreciate abstraction and what is seen beyond the “seeable.”

How might you respond to those who say that abstraction isn’t “real” art, and what suggestions might you give to people without an art background to help them learn to appreciate it?

I think a lot of artists, especially people who consider themselves “fine artists” with traditional art backgrounds and education, have that same “internal perfectionist” that I had growing up when it came to my pursuit of intellectual endeavors and academia. I think there is this idea that if a work of art at first seems incomprehensible, it means that the work has less value and worth since it appears to have required less effort, time, skill, and talent than representational art does. I think that people who don’t understand abstract art at all and are not artists tend to be more literal in the way they perceive and understand the world, and abstract art doesn’t make sense to them because it’s not literal enough. But to me, abstract art isn’t creating “nothing,” it’s creating “something from nothing.” When working abstractly, I am not creating from some “thing” I have seen, I am not creating from some “thing” that exists in the world, I am creating something tangible from the intangible and to me that feels more like magic than anything.

What criteria do you use to evaluate an abstract painting?

How did the person feel while they created it? What emotion(s) were they trying to convey while creating it? How did they feel when they finished creating it? For me, it’s less about the effort and the skill and it’s more about why it’s being created in the first place. I can find art, or should I say, I can find worthy art, amongst every skill level, ability, and medium. It’s much more about the emotion that I feel in response to a piece and the emotion that they felt while creating it. I critique emotionless art more harshly. If someone’s just slapping a hunk of paint on paper to go “viral,” it’s not my thing. Now, if someone is slapping a hunk of paint on paper because that’s the only way they can feel rage, and it conveys the rage that they feel, I’m here for it.

A wonderful question from the book is: “What would be the most nurturing thing I could do for myself based on how I am feeling?” What kinds of nurturing things come up most often for your students or clients, and for yourself?

I think speaking kindly to oneself comes up the most often, because we spend so much time speaking unkindly to ourselves. I think even just being asked the question, “What is the most nurturing thing for you right now?” brings up a lot of emotion for people, because many of them have never been asked that question, or they don’t spend any time asking themselves that question. I really wanted this book to offer the comfort of feeling like you’re with a friend or another trusted person who will see you and hear you and hold you through the creative process. I didn’t want it to feel like I was talking “at you” just to teach you a style.

What do you believe to be the most important thing(s) you have learned through your active art practice and teaching?

To just make art and think about it later. If you hesitate, if you pause for too long, if you tell yourself you will get to it later, you may never get to it, so just make art. Scribble on a piece of paper, draw something in your imagination if you don’t have any materials—but just make art. Make art with your words, make art with your life, make art with your toast in the morning. The more you make art, the more you see art everywhere and the more confident you will be when you create. This will lead to creating more of what you love.

What are your highest hopes for those who follow what you’ve provided in your book?

That they will find something cozy and safe about the process within the pages. That art-making will feel more accessible and meaningful even if the person making it has never been confidently creative before. And, of course, that creatives and want-to-be creatives will speak to themselves more kindly and/or have access to a kinder internal narrative when going through the process of creating confidently.

Might there be another book in your future? If so, please share what it will be about, and if not, what other projects are you working on?

Absolutely! The plan is for Find Your Flow to be a series that expands on the intuitive process shared in this first book with other varied art-making techniques. I have also been developing a text and photography-based memoir/manuscript that encapsulates my therapeutic creative healing journey and process. I’ll be pitching it to agents and publishers this year.

Kristine Morris