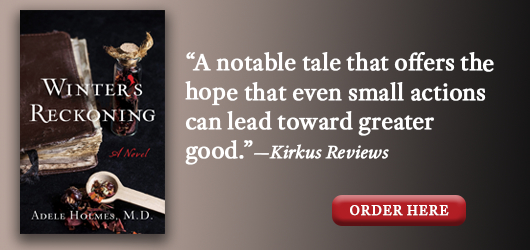

Kirkus calls this "A notable tale that offers the hope that even small actions can lead toward greater good."

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Adele Holmes, Author of Winter’s Reckoning

To be great, a novel needs to succeed on multiple fronts: plotting, powerful openings, character development, dialogue, and so on—all without the reader noticing the parts being assembled. Historical novels, on the other hand, are a different beast—the extensive research and background work required before the author even begins writing is an overwhelming proposition for most writers.

Foreword’s editorial team is always interested to hear from a skilled author who is willing to discuss their craft, and when we discovered her engrossing Winter’s Reckoning, Adele Holmes proved to be an irresistible interview prospect. Executive Editor Matt Sutherland seized the opportunity.

The novel is set in the early years of the twentieth century in the small southern Appalachian town of Jamesville—but trouble’s afoot: segregation is the law of the land, the KKK is on the loose, and crazed, half-wild humans haunt the local woods and caves. What is it about the place and time that first tempted you to write Winter’s Reckoning?

Let me say from the outset that, though the setting is indeed in the southern Appalachians, the story could have sprung from anywhere in the South. My intention was to show the deep divide in the southern populace during that time. Fairbanks Valley in the novel is situated between two mountains, just as the time period around 1917 sets on the timeline of our country’s history between the peak of a tumultuous past and a tidal wave of coming change.

By 1917, the Jim Crow laws had been embraced as a sound remedy to the southern patriarchy having to extend rights to the Black people that were guaranteed them by the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments—the reconstruction amendments.

Many citizens still vividly recalled campfire stories told about the Civil War. Though in the midst of WWI and its trench warfare, WWII with its modern artillery and machines was just around the corner.

Larger cities were expanding in size due to industrialization and the subsequent jobs that lured rural workers; urban populations swelled while rural towns diminished for the first time in our country’s history.

The KKK was believed to be past its heyday, though in retrospect it is now known to have only been in its first nadir. The film Birth of a Nation had been produced two years earlier, but the spread of information—and of resulting change—was much slower than it is today and few in the rural south were yet aware of the movie. Full revitalization of the Klan was not yet realized.

Women suffragists had been toiling for decades, but the 19th Amendment which gave women the right to vote was yet three years away. What is today viewed as suppression of women’s rights was normal behavior for the time.

In other words, the United States, and especially the southern United States, was at a turning point in 1917. How the social issues of racism and women’s rights were handled would determine the future of our country every bit as much as modernization of warfare and urbanization. 1917 was the quiet before the storm.

An herbal healer with a strong sense of social justice, Maddie and her apprentice, Ren, see to the town’s medical needs, along with a twice yearly visit from a traveling doctor. The two women are expert at the art of harvesting, drying, and healing with the wild herbs of their region, in addition to other skills that lean in the direction of spells and special powers. Maddie also hits from a big jug of moonshine every night to chase away her “evening malady” in the words of her granddaughter Hannah. Indeed, Maddie is a strong, principled, complicated woman and she drives the book from start to finish. Can you talk about your inspirations for this character? And, where did you gain such extensive knowledge of the healing herbs you write about?

The inspiration for the character of the protagonist, Maddie, came directly from my maternal grandmother who raised me during the formative years of my life. Though my grandmother was not a healer or herbalist—nor was she a fan of moonshine as far as I know—the very essence of her character is present in each decision Madeline Fairbanks made. It was my grandmother who taught me, more by example than by instruction, the values I stand upon today: respect is not doled out according to the color of a person’s skin, one’s self-worth is not diminished by anyone else’s whim or declaration, wealth is determined by a life of integrity and not by net worth. I wanted to capture her wisdom and goodness to preserve it for future generations.

As far as knowledge of herbs, much research was involved. Being a physician, describing the diseases and illnesses came easy to me. But it was fascinating to learn how treatment differed in the rural areas of 1917. Herbs and plants are the basis of most modern pharmacology, so there is a vast quantity of documentation as to what herb was developed into which latter day medication. Digging through old texts, mostly online, became a favored pastime which consumed hours and days. Then, once the cure was chased down, I had to make sure it was available in the region. It seemed there was always another fact that needed to be substantiated before I could move on. But I think that’s what makes most historical fiction writers tick, the research.

Next in the line of family healers, Maddie’s preteen granddaughter, Hannah, shows remarkable healing skills at a young age. But, at ten years old, her precocious healing abilities and inquisitive nature in a world of adults, often find her overwhelmed by life’s cruelty. You write at one emotional moment: “Hannah tried to work up a real cry, but she wasn’t able to. She had learned the how of the hard ways of the world these last few days, but the why was still a mystery to her.” Hannah is also one of three characters—the other two being Maddie and Carl—you tell this story through. So, how was it to channel your inner ten year old? Did the Maddie-Hannah-Carl rotation cause problems at times?

The story was indeed told through three disparate points of view. Rather than causing problems, I feel that adding a child’s voice and the antagonist’s viewpoint to the story gave so much more texture and complexity than I could have done with just the protagonist’s point of view alone.

It is such fun to write through an unreliable narrator, such as with ten-year-old Hannah in this case. We all remember what life looked like at ten, right? Much more black and white, more cause and effect, very concrete. So much less insight because of inexperience. Hannah’s arc was rewarding to write as well—she went from unreliable narrator to speaking truths in a way that only the innocent can.

To the question of whether rotating through three dissimilar voices was problematic, the answer is a resounding “No.” The triangulation of sage, narcissist, and unsullied rounded out the story to its fullest extent. How better to mirror all the nuances of the ugliness in society; how better to strike a flicker of hope for a better world?

Carl, the pompous new preacher, arrives in town astride a spectacular horse and, messiah-like, proceeds to both mesmerize from the pulpit and meddle in everyone’s affairs as he makes his rounds visiting parishioners. “A fascinating case study in narcissism,” Maddie calls him. Eventually, we learn he has a very sinister late-night side gig with some other hate-filled men. So, our preacher is a piece of work. How was it to speak and narrate through him?

I loved it! Climbing into the skin of the vain and vicious, as a writer must do to produce a three-dimensional character, was invigorating. I’d originally thought it might be challenging, or disturbing. But as the puppeteer, I was able to lay bare the vileness of the antagonist, all the while knowing how it would result in his undoing in the end. As I said earlier, the deep divide and cruelty against one another that I witnessed arising again in our country was the motivating force of the plot. To present an antithesis with a glimmer of hope for the future was cathartic.

Carnavan’s Cave is the stuff of every child’s nightmares, but Hannah overcomes her fears one morning to pay a visit. We subsequently learn that the cave’s terrifying reputation has some basis in truth because of a wild boy, the Harris boy, perhaps product of incest, who lives there. Can you talk about how myth, legend, and a palpable sense of the unknown haunt a people and a place, especially one as isolated and inward looking as parts of Appalachia, and why you found it such an interesting backdrop for your first novel?

I must quite simply face the fact that I am in love with the South, though I frequently rail against our transgressions.

We in the South, including Appalachia, bear the brunt of many unfounded beliefs that all are ignorant, inbred, uncivilized. This is in no way my mindset, nor do I wish to show Maddie as a northerner come to be the savior of the area. The fact that Maddie came from Boston is based upon two facts: my own family tree reaches back to that area, and the backstory and sequel required it. I hope that it is clear that the protagonist is also in love with the South, and wishes to remain there.

Having said that, a good southern gothic drips darkness, reeks of the grotesque, and invites the reader into the macabre. The lands of the southern US are a repository of all such things. I posit that “place” is the driver of southern goth. Place, with its blood-stained soil and its harrowing history of slavery, is the absolute necessity—more than character or plot—for a true southern gothic. Not necessarily Appalachia. Any southern place will provide the same effect. But it was the beauty of the Appalachian Mountains that caused me to set the story there. That, and the fact that the Appalachians cover more of the South than any other named area.

You may note that my story does not name a state, and its cities and counties are fictional. This was purposeful so that the reader could place it anywhere in the South that their imagination demanded. The South holds all the requirements for the making of myth and legend, for ghost stories and hauntings, for penances owed and unrequited.

With such a diverse cast and so many competing interests, you found ample opportunity to create many compelling confrontations: between Maddie and Carl, for example, and also racial tensions between characters, and scenes depicting the blatant sexism of the times. You also don’t shy away from violence in the book. What do you think is the secret to creating a riveting scene and where did you learn the skill? What writers inspire you?

Most of my knowledge about good writing came from good reading. I’ve read literary classics all my life, amongst many other genres. I took courses, classes, and workshops on the art of writing, but claim no credentials to school others in the art of scene development. However, these are the things I try to include in each scene:

-

Realistic dialogue: the characters should be doing something while they talk.

-

Use all five senses in every scene, or in as many as possible without sounding contrived.

-

Most importantly: each scene (and indeed each paragraph, each sentence) must drive the story forward. No matter how beautiful the prose, if it doesn’t drive the story forward, it must go.

Some of the writers I’ve been most inspired by are: Barbara Kingsolver, Sue Monk Kidd, Donna Everhart, Toni Morrison, Madeline Miller, Charles Frazier, William Faulkner, and the list could go on and on and on.

What do you hope readers take away from Winter’s Reckoning?

That our past as a country has at times been egregious, that we may be at the precipice of repeating those atrocities, and that small individual acts can have a huge impact in preventing such recurrence.

What’s next for you in your writing career?

I am still in the thrilling process of marketing Winter’s Reckoning. I’m so excited to be able to share two announcements here:

-

The audiobook has just been published and is in the process of being loaded onto all audio-media outlets.

-

In February, for a limited time, the ebook edition of Winter’s Reckoning will be promotionally priced at ninety-nine cents, wherever ebooks are sold.

I’m also at work on a sequel which will include much of the backstory to Winter’s Reckoning, at least in as far as the maternal inheritance of Maddie’s healing craft (hint: there were witch trials in 1550 in Bergen, Norway). The setting for the story will be an urban medical center in contemporary times. I had intended for it to be set in Boston, but after writing Winter’s Reckoning, I have decided I will continue with the southern gothic theme, and will set it in New Orleans.

So that will make it a medical mystery, historical, literary, southern gothic?

Matt Sutherland