Legendary Baseball Writer Talks Greatest Hits & 2017 World Series. Meet Mark Newman, author of Diamonds from the Dugout: 115 Baseball Legends Remember Their Greatest Hits

To err is human. To err at batting and fielding balls is the defining feature of America’s favorite game. Even the best who play professional baseball are successful at hitting the ball only three times out of every ten attempts. And because of all that failure, retired professional ballplayers tend to remember most of the singles, doubles, triples, and home runs they swatted over the course of their long careers. One of baseball’s top writers, Mark Newman posed the very succinct “What hit meant the most to you and why?” question to more than one hundred legendary ballplayers, and their answers make for mesmerizing, often emotional reading. We caught up with Mark to talk baseball, his book, and the World Series, cuz it’s game on between LA and Houston.

John McEnroe once said that he got so upset on the court because in the course of a typical match he’d make dozens of unforced errors and the mental toll of all those mistakes drove him crazy. Baseball is almost the opposite—limited opportunities to hit in each game with a dreadfully low probability of success and long periods to stew about failure. That also sounds like a perfect recipe for rage. Is there a common personality type for the best players in baseball? How do these guys stay sane?

Since I began as a sportswriter at The Miami Herald in 1982, I have found that the hallmark of the greatest athletes, in addition to pure talent, has been the simple act of having an even keel. They don’t get too high and they don’t get too low. I have seen it in Michael Jordan, in Martina Navratilova, and in baseball legends like Derek Jeter. He perhaps answered your question best when I interviewed him during the 2009 American League Championship Series. Standing in front of his locker, a game away from another World Series, Jeter said, “If you treat every game the same, you’re able to slow things down a little bit.” The great Carl Yastrzemski committed an egregious error in left field at Fenway Park on the last day of the 1967 “Impossible Dream” season, but he atoned for it with a home run and for that reason he cites it as his favorite of 3,419 hits. That is far better than rage, and a valuable lesson in Diamonds in the Dugout.

Most of the ballplayers you interviewed had careers that lasted for fifteen or more years and included hundreds, even thousands of hits, so it’s remarkable that they could all pick one. Did you note a pattern or common denominator between the guys as they mentioned their most memorable hit? First hit in the majors, or first home run, for example.

Most legends will go back to their first hit, especially if they are in a hurry. It often depends on the setting, how relaxed and informal so that their minds can wander. Often the legend will begin by saying, “That’s unfair to the other hits” or “I don’t know if I can do that.” Then I would let them know that Cal Ripken said this or Lou Brock said that. That extra reference bought the subject some time, allowing his career wheels to spin, and suddenly they would come up with a gem. Then I would follow up to recall more about the situation and what he learned. Another pattern I discovered early on was that an iconic hit we all remember is usually not how the author of that hit will respond. Joe Carter’s famous 1993 World Series-ending homer in Toronto landed right in front of me, I spent a day with him that next month in Kansas City for a magazine cover story, and yet a quarter century later he was telling me something totally unexpected about a grand slam off a legendary ace early in his career. Only one player said he just couldn’t pick one: Graig Nettles.

You’ve spent thousands of hours in ball parks and locker rooms watching games and interviewing ballplayers. What is it about the game and its players that kept your interest for so long?

It is the game I played as a boy, the game I played against Don Mattingly in our hometown of Evansville, Ind., the game that draws about 73 million fans a year in the Majors and so many more in Minor League towns across the continent. It is the game I attended at age 2 in the Minnesota Twins player wives section, because my uncle was playing for the Twins, the same game where Jim Kaat’s teeth were knocked out that day. It is the game I taught my three sons, one of whom is included among the 115 legends, because the moment was legendary to me. It is the game where Ripken reached 2,131, the game where Big Mac hit No. 62, the games where the Red Sox and Cubs reversed their curses, all those games I saw in person. It is the game where parents and children can have conversations in the stands while leisure moments in fresh air make you mostly peaceful and happy. It is the game of Musial and Banks and Killebrew and Yogi, and whenever we lose one of them it hurts equally as badly as it was joyful when they filled our days and nights. There is so much magic in the game, and I want to do my part to make sure no one ever takes it for granted. It’s baseball!

You’ve been collecting these interviews with great ballplayers and working on this book for quite a while. How was it to finally sit down and put it all together. No doubt, it brought a flood of memories. Was it enjoyable? Did it cause you to reminisce about the different eras of the game? Before social media, twenty-four hour news cycles, etc., were players more open and accessible?

It has been a hobby for the past decade. Some people collect trading cards; I collect legends’ favorite hits. I feel like I am just displaying my collection now. Each hit was written after it was transcribed, so it grew over many years, but ultimately it was time to make the manuscript flow, and to extract all the lessons and group them by chapters. It was truly a passion project over that time, with Alex Rodriguez the final addition before the press file was delivered. One of the most joyous moments for me was the day Brooks Robinson called me to tell me he loved how it turned out and how much he enjoyed reading his friends’ responses. Brooks’ call took me back to my boyhood, listening to his World Series exploits on my transistor radio. It took me back to historic Willard Library in Evansville, where my grandmother would take me to check out books each week. I read every Matt Christopher book possible as a boy, so I suppose it was a mission that I would one day write a sports book. My peers may disagree, but I don’t think the stars are all that different today than they were back then; if anything, they have more interaction with the public now so you can readily find an idol.

So I noticed that Pete Rose has a whole chapter to himself.

I could not write a book about hits without including the one who had the most, so it was a given that he would be in the book. But I had no idea what I was getting myself into. On the morning of Game 7 of the 2016 World Series, arguably one of the biggest days in baseball history, I got a wakeup call in my Cleveland hotel. It was Charlie Hustle. I scrambled to open my laptop and put him on speaker and started typing. He began a stream of consciousness that lasted 45 minutes, and I was concerned that he was going to literally go over every one of his 4,256 hits. He discussed so many before finally settling on a winner, and gave such a clear lesson about setting goals, that there was no doubt he was going to be his own chapter. Whatever you think of Pete, he is the king of that mountain.

What was the hardest part of putting Diamonds from the Dugout together?

It was the realization that I could not include everyone I wanted. My access to baseball legends has been beneficial, but sometimes the timing just did not work out. Rod Carew was my idol as a boy, but he was undergoing a heart transplant as I wrapped up the manuscript. It really hurt not to have him in the pages. I have basically every 3,000 Hit Club member, so I wish I could have gotten to Ichiro as well. I tried both Willies (Mays and McCovey) in San Francisco, but hopes for access last Opening Day fell through. I have about 45 Hall of Famers and a long list of legends, and we can add more as needed when it hits paperback.

What are your thoughts on this unique World Series matchup: Astros vs. Dodgers?

I’m really happy for both fan bases, because it would be meaningful to both for different reasons. But I have to be honest with you: I miss a good baseball dynasty. I’m kind of tired of the no-repeat streak. Once the Cubs were knocked out, that made it 17 consecutive years without a repeat champion, which is now the longest active streak in global pro sports. That has been something for us in MLB to tout, because competitive balance is a good thing. I get that. But enough is enough. I miss seeing a true dynasty, like the Yankees from 1998-2000, or like the Big Red Machine and Swingin’ A’s of the 1970s. Heck, even the Blue Jays of 1992-93. The road is filled with too many obstacles today, with a 10-team postseason, with complacency, with player movement. If the Dodgers win, good for their fans after waiting three decades. If the Astros win, good for the whole city after Harvey. I just think that in team or individual pro sports, it is important at some point to bow at the feet of a real king or queen, to experience that sustained greatness. As for this 113th Fall Classic, I’ll look forward to running into Craig Biggio to thank him for his 3,000th hit in the book. I’ve interviewed both Justin Verlander and Kate Upton separately over the years, so maybe I can start a sequel about baseball couples. And as I savor the Southernmost Series ever, with my luggage full of warm-weather gear, I’ll find myself wondering who will deliver the memories of a lifetime—and if that player will think back one day and consider a heroic feat from this World Series his own favorite.

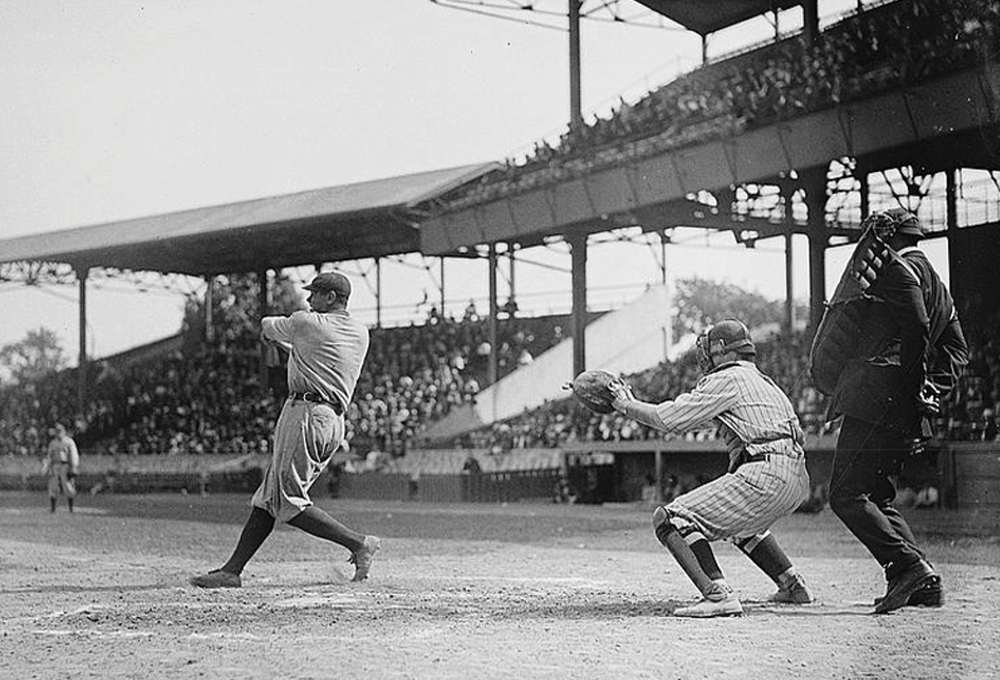

Note: All photos courtesy of Diamonds from the Dugout: 115 of Baseball’s Greatest Hits from Baseball Legends by Mark Newman. Used with permission from Blue River Press.

Matt Sutherland