“Life. Music is life. Music is a reflection of who we are as humans….” - Susan Graham

Executive Editor Matt Sutherland Interviews Larry Ruttman, Author of Intimate Conversations: Face-to-Face with Matchless Musicians

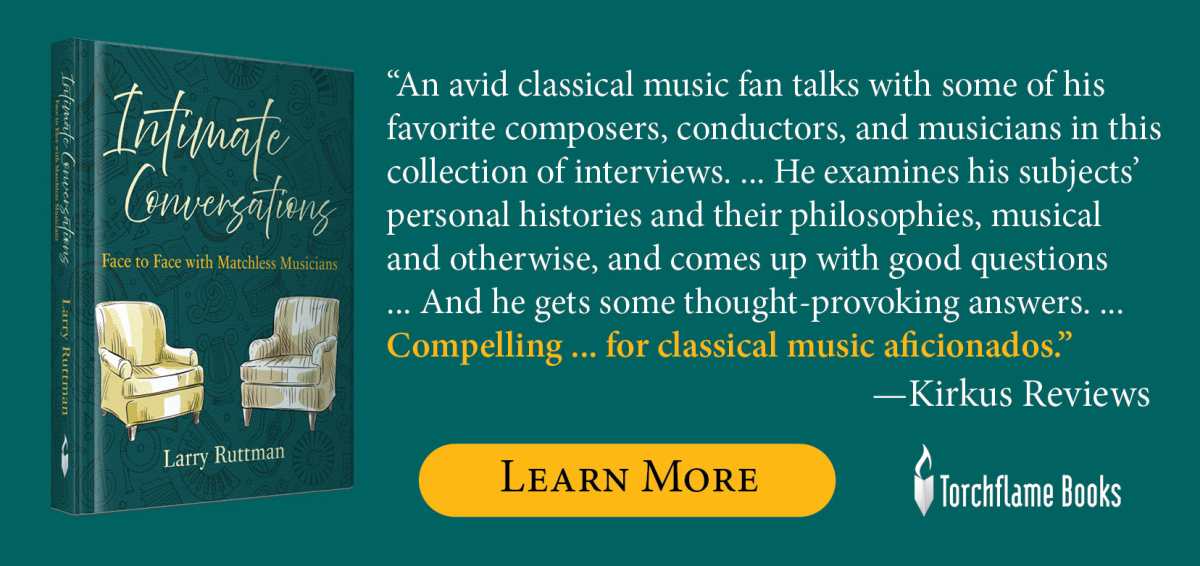

“An adventurous odyssey to unearth the depths of great musicians’ psyches and to discover the wellsprings of their creative powers” is how Larry Ruttman describes the writing of Intimate Conversations: Face to Face with Matchless Musicians. That he became friends with so many of the musicians enriched his life beyond measure. In the book, he has sought to give readers the confidences these artists gave to him in an interesting and entertaining way. He has included all twenty-one of the musicians in these answers.

Most books about musicians are written by other musicians, and tend toward the technical. Here a layman succeeds in making these musicians come alive as people, as well as musicians. The book immediately does that in the opening chapter on acclaimed American composer John Harbison—arguably the greatest American composer now living—who confided personal insights in ordinary vernacular on his compositional process and personal life in a two-hour conversation at his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Larry’s idea that a non-musician, unburdened with musical technicalities and language, could get deeper into the minds of the masters was demonstrated when Harbison later wrote a letter to the author in which he expressed his appreciation for the story, and how Larry’s knowledge and bearing made him comfortable to tell his story. That handwritten letter appears on the back cover of this book, as do four other handwritten letters of the same ilk from notable American composers Joan Tower, Robert Levin, Matthew Aucoin, and Osvaldo Golijov.

Here’s Larry talking about his intentions in writing the book:

“My talks with these composers, conductors, instrumentalists, crossover musicians, and an honored administrator, touched on a plethora of topics, musical and personal. Those turned into warm friendships in almost every encounter. My original intent to probe into the psyche of the musician, to reveal the nucleus of expressive power, remained to a greater or lesser extent in every story, but I found there is a limit on how long that subject can be maintained—but practically no limit on how long two people interested in one another and their subject can fruitfully converse. You can see that atmosphere in the very first story on John Harbison, and in all the others, to my amazement and gratification.

“You may wonder why I call them stories. The interview is only the raw material. I then decide what it is about the musician’s life that gives it importance and meaning. That is stated in the introduction of each story, and then the material gleaned is given order to suit that notion. Thus, the heart of the book, as I see it, is that these stories are actually short biographies. The final paragraph concludes with words intended to briefly restate the meaning of that musician’s life. A main theme of the book is the inspiration we take from the compelling and collaborative personas of this gifted array of musicians, especially in these fraught times.”

These intimate conversations cover a range of topics: profound, poetic, and merely prosaic, which will draw in all lovers of music, musicians, and regular people. As such, it is believed that Intimate Conversations has an originality which will entrance and fascinate.

Matt, let’s get this conversation started.

You, a music-loving layman, have been blessed to speak with twenty one virtuosos of music—composers, conductors, vocal and instrumental artists, and big hitters from the music world—for this project. Before we get into their individual genius, can you talk about some of the traits they share? What do world class music people have in common, personality and otherwise?

I think the operative word here is “love.” Musicians love music. They love the composers who have written that music. Perhaps most striking is that musicians love each other. I am speaking in general terms, of course. Furthermore, whether in orchestral music, or maybe most lovingly in chamber or small music combinations of two to thirteen or more, musicians love to collaborate.

As I write, I think of Mozart’s Gran Partita for Twelve Wind Instruments and string bass, K. 361, an almost hour long masterpiece of great emotional and musical depth. I also think of his achingly beautiful Sinfonia Concertante for Violin, Viola, and Orchestra, K.364, which violist Kim Kashkashian notably recorded with violinist Gidon Kremer, and violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter recorded with violist Yuri Bashmet. Perhaps this composition features the long neglected viola, said to be Mozart’s favorite string instrument, more than any other before or after.

Also, musicians love to connect with their audiences, rising to heights of expression when they know the audience is tuned into them. One night thirty or more years ago, I braved a blizzard to walk to Symphony Hall from Brookline two or so miles away, to hear the late great cellist Lynn Harrell play Dvorak’s exquisite cello concerto. The hall seats 2,500. Maybe a few hundred showed up. What a reward we won! Harrell played his heart out in a transfixing and tear drawing performance that none of us will ever forget.

As I look over the preface I wrote for Intimate Conversations, I am struck again how high my opinion of musicians is, and how many adjectives it took to convey that opinion. Perhaps that is consonant with my belief that music is life. I find musicians to be articulate, politically tending to the liberal, highly educated, very literate, humanistic, civilized, friendly, open, each with a different and interesting persona, knowledgeable about the history of the arts, especially the history of music, peaceful, generous, gentle, humorous, charitable, hard working to bring pleasure to their audiences, proud of being musicians, pleased to teach their art to others, collaborative with their peers, students, and others.

Take Larry Lesser, famous as a cellist and President of The New England Conservatory of music, who invented First Monday there, which for years and for free entertained thousands with a rich panoply of music.

Or composer Osvaldo Golijov, transplanted from Argentina to Brookline, Massachusetts, famous for his original work, “La Pasion Segun San Marcos,” and for his teaching for over thirty years at the College of the Holy Cross where he was honored with his appointment there as the Loyola Professor of Music in 2007.

Or erstwhile clarinetist Mark Volpe, who became an attorney, and rose to become the President and CEO of the Boston Symphony Orchestra for twenty-three years. In that role he guided it to orchestral excellence, formed a beautiful partnership with gifted conductor, Andris Nelsons, increased the orchestra’s endowment substantially, and administered the ensemble under his powerful leadership.

Do musicians have differences? Of course. They are human. But they are a special breed, perhaps unique in humankind.

Musicians talk about all the composers, but seem to talk of Mozart the most. I confess that might be due to my questions, but It has occurred with some whose muse is another composer. Bach and Beethoven come up often, as well.

I think all musicians believe music to be the greatest of the arts, and to a person believe they could not live without music. Even as a lay person, I feel the same.

How long has this book been percolating? Please give us a sense of the time frame from when you first started the interviews and then made your final edits on the finished manuscript?

I believe this book has been percolating in my inner psyche since I became a regular concert goer and reader about music at around thirty. All through my forty-plus years as a lawyer, I continued my passionate love of music. After cutting my time as an attorney around 2000, I turned to other interests, among them chairing an hour long weekly television series of interesting Brookline folks, of which there are many—some famous, some not. This led to my first book, Voices of Brookline, published in 2005, the year of Brookline’s tercentenary. That book won a gratifying reception. I was hooked on writing.

Always a baseball fan, and always proud of my nationality and ethnicity, I next wrote American Jews and America’s Game, published by The University of Nebraska Press in 2013. To my astonishment, that book was chosen the best baseball book of the year by Sports Collectors Digest, among many that year. In actuality, that book is as much a cultural history as it is a baseball book, tracing American Jewish history back to the Great Depression and earlier. At that time, the percolating idea bubbled into my consciousness, and in my naturally optimistic and confident way, I came to believe that I, a mere layman, had something to say about serious music and musicians in a natural vernacular which people would like.

Blessed or cursed with an abundance of chutzpah, I had no hesitation to approach these world class musicians, and ask for their personal time in his endeavor. After all, we are all humans, all headed to the same place. I also believed that what I had to say would be a rarity in that most books about musicians are by musicians or people with a formal connection to that world. As it turned out, no other book has been uncovered using the approach described. In fact, my technical lack of musical knowledge likely helped me to connect to my interviewees person to person. Those feelings increased with every interview I did, and as I became friends with these esteemed artists. That continued until the final edits on the book around 2020, shortly before COVID struck.

During that crisis I began work on a memoir entitled Larry Ruttman, A Life Live Backwards: An Existential Triad of Friendship, Maturation, and Inquisitiveness. It is now completed and up to date. I hope to publish it in a year or so. Of course, no memoir is ever completed. Nobody knows what will happen tomorrow.

Composer John Harbison talks about the qualities of perceptivity that made Mozart, Mendelssohn, Wagner, and other legendary composers. “It takes a lot more than mere instinct to make operas as comprehensive as those of Mozart with such subtlety of thought. That takes a lot of intelligence and a lot of culture. None of that is just happening simply by genius. It’s happening because somebody is there who puts many, many things together that are there needing to be assembled.” He seems to be saying that these greats needed to live a big, rich life to create such genius in musical form. Can you flesh that out for us?

I would offer that the genius was born with the composer, and not created later by the life each led. I don’t think John Harbison would disagree with that statement. The perceptivity needed must be a facet of the composer’s character, whether he or she was born rich or poor, or wherever. That is part of intelligence. Culture arises from experience. Mozart traveled widely from a very young age. Most renowned composers started musical studies very young. That builds culture and sophistication. The assembling of those factors lies in the composer’s intellect. Mozart enjoyed a big, rich life. One could say that Mendelssohn, Wagner, Haydn, and others lived richly from youth. One might not say that about Schubert, Verdi, Schumann, and others. But all of them developed over time as their respective experiences mounted.

That is where “genius” comes into play. Can anyone explain how Mozart created The Marriage of Figaro, with its uncanny truthfulness about the human condition told in astounding and gorgeous music? The same might be said of Richard Wagner’s Ring cycle, where one man composed and wrote the music and the words. The inborn genius of all great composers is the key to what allows them to convert the experiences of their lives into works of lasting quality.

In your intro to the conversation with Robert Levin, you half-jokingly refer to him as Mozart reborn, a compliment of the highest regard for his “ability to inhabit the mind of that master,” you say. About Mozart’s greatness, Levin says “ I do think that what separates Mozart from virtually everybody is that he has a knack for characterization and for the understanding of the human condition, which is equaled, as far as I am concerned, only to Shakespeare.” Can you expand on his statement to give us a better sense of what he means by that?

I’m not quite sure where I got the Idea that the three greatest dramatists in the history of the modern world are Shakespeare, Mozart, and Verdi, but I still agree with that notion, for sure. Robert Levin restricts that accolade to the first two. Levin’s quote says it all. I’m not about to say I can improve on Robert Levin. He is a genius himself, a renowned professor, pianist, composer, writer, and humanist. I can offer that once you hear Figaro done well you never tire of its revelations about practically every human relationship you can think of. Where did Mozart get the power to do that? It can’t be explained. Mozart himself could not have explained it.

This book attempts to approach closer to the explanation, but no one will ever get to the nucleus. The same is true of the works of Giuseppe Verdi, and to a lesser extent, to the works of a plethora of composers and dramatists. That is why great art lasts. It holds a mirror up so we can truly see what we are really like; the human condition, as it were.

What about the composer-Shakespeare affinity or connection?

I interpret this question as why is it composers have so often looked to Shakespeare for inspiration. I think the answer is because Shakespeare sought the same truths as the composer, especially composers of opera, ballet, and dramatic works, and he did so in poetic, original, and beautiful language that clearly revealed the human condition to its audiences. Thus, composers were inspired to draw from Shakespeare’s plays, even as translated to their own language, to restate those revelations in musical terms. The bond between the Bard and composers is indissoluble, and now extends to playwrights and composers generally.

Your conversation with composer Joan Tower features some great historical commentary on women in music: the infuriating sexism and lack of opportunity, as well as more hopeful details about successful women composers, musicians, and conductors. Of course, this is an immense topic, but has the tide turned enough so that women are given a fair shake in the industry today?

Whether the shake is fair to women today I can’t definitively answer. It is much more fair than in earlier times, but whether it has reached the point of being truly fair is questionable, despite many more women composers, players, virtuosos, conductors, and managers. I think here of noted pianist, beloved teacher, and author, Aiko Onishi. I think too of violinist Cecelia Arzewski who rose to the position of Concertmaster of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. I think especially of original composer Unsuk Chin, thought by many to be the greatest distaff composer in the world today. As said, Joan Tower is a tower of strength as a composer, player, collaborator, and professor. However, there can be no doubt, men are treated better.

The question brings to mind two other questions. Are women compensated fairly? One thinks of the case brought by the terrific first chair flautist of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Elizabeth Rowe, seeking $200,000 in back pay because she was paid $70,000 less per year than her closest male peer. The case was ultimately settled, presumably favorably to her, followed later by her resignation from the orchestra. The other question overarches the classical music scene, which the Rowe case suggests, is whether it will survive its problems.

In this book, the story of Monica Rizzio is germane. It suggests that female artists are better treated in the pop world. But even there, watch out if you oppose the agents and gatekeepers because they will put you in your place, as strong willed Monica found. Today, she heads her own music school which she founded on Cape Cod, performs occasionally, and enjoys a rich family life. The same can be said of super-talented and courageous Eden MacAdam-Somer, who chose family, three children, and academia instead. She too performs occasionally, and serves as the co-chair of the Improvisation Department of the long established New England Conservatory of Music.

Thinking of Eden brings to mind a great story that shows the power of women, among other facets. Having enjoyed a friendship in the past with the celebrated soprano and lovely woman, Renée Fleming, I asked her if I might use a photo of her to head the “Crossover Artists” section of the book. Renée did not like either that title or the photo I proposed to use. She proposed another title and offered a favorite photo of herself. So I asked the brilliant Eden Macadam-Somer if she could think of another title. If you can believe it, Eden came up with three great titles in half an hour, one of which was “Beyond Genre,” which is the one Renée immediately chose, and which now heads the section—along with a photo of the gorgeous Renée. Thank you, Eden. Thank you, Renee.

Is that the end of the story? Not quite. Recently, I asked Renée for an endorsement of the book, sending her a PDF of the text and the fifty-five or so photos in it. Her response is off the charts:

“Larry Ruttman’s Intimate Conversations: Face-to-Face with Matchless Musicians opens a fascinating window into the lives and creative processes of some of the leading music makers of our time. Erudite, inquisitive, and gifted with the ability to put his illustrious subjects at ease, Larry elicits heartfelt and strikingly candid interviews. Any reader of these indepth encounters with great musicians is certain to gain a new understanding and appreciation of their artistry.”

Certainly the treatment of women is better than in the day of Fanny Mendelssohn, sister of Felix, whose super musical talent was almost totally restrained by her society family. Brother and sister were very close. One wonders whether this history accounted in some measure to the early demise of each. Somewhat better was the fate of Clara Schumann, wife of the great Romantic but ill-fated composer, Robert Schumann, who managed to gain superstar pianistic status for half of the 19th century.

Also in the Joan Tower interview, you ask about her thoughts on pop music and she says that it “looks like a healthier culture from the outside than the classical music world because they keep up with new stuff all the time.” It’s interesting to hear her use the word “healthy.” Can you talk a bit about both the healthy and unhealthy sides of the music industry?

I think Joan Tower was thinking about classical music surviving as an industry rather than of “health” as a medical term. In that context, classical music is way more healthy than pop where drug and other deaths occur every other day. But pop plays to enormous crowds all around the world, and earns in the tens of billions. No one thinks it will go away anytime soon, as some do think about classical, as short sighted as that may seem. John Harbison, a jazzer better known as a classicist, takes the view that classical music is on the way out. To dissect why that may be would take a book. In fact, that question is taken up in this book by Harbison, Ran Blake, and others. God forbid that would happen!

Perhaps it is a measure of modern culture that so many follow the beat of pop, and the brevity of its songs, and so few have the attention span to be brought to deep feeling as well as enjoyment by the subtleties and complexities of classical music. I believe music is life. If the sublimity of classical music disappears, would that not be a harbinger of the disappearance of man to soon follow? I, for one, believe Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Rachmaninoff, Mahler, Gershwin, and all the others will survive. Listen and watch the ill-fated Jacqueline du Pre play the Dvorak cello concerto, or any of the other ones she recorded before her untimely passing, and you will believe too.

How not to come away from this book awestruck by what amazing people musicians are—at least the ones you selected to interview? Thoughtful, worldly, kind, humble, courageous, generous, on and on. Conductor Benjamin Zander offers a perfect example when he responds to your question about what drives him by saying: “I have a passionate desire to bring along as many young people as I possibly can to be fully effective, expressive, and contributing human beings.” What is it about music that attracts such saintliness? Or, perhaps it’s a nature-nurture question. Does music fill their soul with goodness or is innate goodness what pushed them toward music?

Music is a force for good because it brings out the good in people. Generally, that is how music is used. On occasion, its power is used for bad, as the Nazis did. The adjectives you chose are very descriptive of musicians. I find them to be like that, and my good friend Maestro Benjamin Zander is a perfect example. His quote truly tells it all. Just last Saturday I spoke to Ben, finding him at home in his sickbed with Covid only three days after returning with his Boston Youth Philharmonic Orchestra (BYPO) from a multi-week and multi-city European tour. There he intermingled, of course, with scores of people along the way.

All people, including musicians, have multiple sides. At first I was conflicted about Ben’s persona, despite his notoriety even then. Over time I came to understand him, and finally to love him for those saintly qualities which his quote accurately portrays. So it is a two-way street. There is good and bad in all of us. Music brings out the good. The more passionate the musician is about music, the more he will give back to his fellows. Ben Zander is super passionate and super generous. He teaches both music and life to the children and adults he leads in music and travel. Yet another point to add to my belief that music is life.

You write at one point, “Maybe the main purpose of this book is to get composers to reveal their musical minds so we’ll know what went on in Mozart’s or Beethoven’s head that allowed them to create such wonderful music?” With some distance now from finishing the book, do you feel like you can answer that question?

As I said, no one can answer that question, not Mozart, not Beethoven, not any composer. But by questions not often heard or ever asked, one might gather insights into the creative process. One such question I used often was, “What is music?” Seemingly simple, it elicited a wide variety of answers, usually after a pause to form the reply. That pause told me I had hit the mark. The most memorable answer to that question came from an instrumentalist, not a composer, the great diva, mezzo-soprano Susan Graham, who with no delay, spontaneously and incredibly delivered the following words:

“Life. Music is life. Music is a reflection of who we are as humans. Music tells us things that words can’t, it ignites feeling in us that we didn’t know we had, and it can reach a depth that nothing else can,”

I was so thunderstruck by Susan’s reply that I used it on the frontispiece of the book above a famous portrait of Mozart.

Another story shedding light on the idea that music is life relates to the late and highly respected English conductor Colin Davis, whom I saw many times conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Davis’ wife, Shamsi, died while he was in the midst of conducting a run of Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro at the Royal Opera House in London. Despite his profound grief, Davis continued the run just days later. Asked how he could do that, he replied, “It comes from the music. There is so much negative nonsense talked about Mozart, but he is—well, he’s life itself.”

As this and other answers to this engaging set of questions make clear, I stand with Susan Graham, Colin Davis, and many others who share this belief.

Asking personal questions somewhere out there in the Never Never Land between the normal limit of acceptable questions and close to ones truly unacceptable, will often bring out answers never before heard. I asked composer and pianist Ran Blake, “Do you have confidence in your talent and genius, if you will, for making music, whether by composition or playing?”

That question elicited a revealing answer from a polymath who is an acknowledged genius in his playing, composing, teaching, and writing, as well as a winner of a MacArthur Genius Grant, a humble person who shows it’s all about you, not him, when actually it is the reverse:

“I don’t know if I’ve ever been asked that question. I’m not sure I can address this. I see you’re going to make me work today. I think in many ways I don’t have confidence. I mean I’ve gotten some nice awards. I’m just flabbergasted by the question, but I really don’t know if I have confidence or not. I don’t know [sounding somewhat surprised]. I think maybe I don’t.”

When asked what it feels like to be a conductor, Gil Rose makes the quip that “it’s the only profession other than a priest where you have an audience on both sides of you, in front of you, and in back of you. You are being judged from all directions constantly. It takes a certain kind of personality to do it.” In your conversations with Gil and the other conductors, what else about their personalities stands out?

Conductors are like people.They come in all shapes and sizes. Watching Seiji Ozawa from behind him for many years in Symphony Hall was a view that demonstrated his elegance and grace as he conducted. Lately, seeing him from the front on YouTube showed me what a skilled, intense, and demanding leader he was.

Gil Rose, growing up in hard scrabble Pittsburgh, brooks no nonsense from his players. Gil gifted me with an extended tutorial on conducting that opened my eyes wide to the art. Charles Dutoit, from an ordinary family in Switzerland, may well be the best conductor in the world. No question, he has collected the most honors. His strict bearing gives him the ability to master huge forces of orchestra, chorus, and soloists in works of masters, like Berlioz’s Damnation of Faust. Englishman Harry Christophers wins us and his players over by his warm charm and mastery of old and usually religious music. When I first met Harry among a group backstage at Symphony Hall after a performance, we became “Harry and Larry” to each other in less than a minute. Martin Pearlman is a truly gentle man whose underlying toughness as a conductor, player, composer, teacher, student, and administrator have allowed him to create his world famous Boston Baroque.

Let me not forget hometown hero, the late great conductor and all things musical from Broadway to Tanglewood to Symphony Hall, Leonard Bernstein, perhaps America’s greatest musician ever.

Does listening to great classical music improve our mental health? What happens in the capable minds of devout listeners of classical music?

One hears of the Mozart effects which is thought to calm highly agitated people. After I play music late at night to settle me down after a long day, it invariably does. It clears the mind for sleep. Often, as I listen to music never before heard, or a different interpretation of a familiar piece, it provokes thought and inquiry. So my answer would be that music does improve mental health. Of course, that answer is not scientific, but I would bet it is accurate. A good proof too is the good mental health of musicians, as said above. That does not mean they don’t have their differences, whether with other musicians, wives, children, or others. They are humans after all.

Are you optimistic about the future of music? It’s certainly discouraging to think about a future without music.

As said above, there seems to be some doubt about the viability of classical music and little or none about pop. I am a born optimist. I see classical music lasting far into man’s future. Bach and Beethoven will sound until man’s end. So might pop, as well. But the forms of pop will change as fads change. Some will prove lasting, but a lot will not. Anybody who opines on this issue is stating an opinion only. Nobody knows. The only thing for certain is that there will never be a future without music. As I said in my afterword to this book, music was here before us and will be here after us. Man’s history on earth will be short compared to the zillion year history of planet Earth. Music began when the earth began, and will exist when the earth disintegrates after its very long existence. That raises the question once again whether music is about life, or is life. Thus viewed, it seems the latter is the answer.

In your mind’s eye, who did you imagine as your readers when you set out to write Intimate Conversations: Face to Face with Matchless Musicians? Why should they buy it?

(I’ll answer this question speaking directly to readers.) It appears there is no other book like this where a lay person with absolutely no musical training, just like you, except for the musicians who read it, is seeking to make classical music, often thought to be hard to understand and unapproachable, bright and clear in order to enhance immeasurably your enjoyment of life. To a lesser extent, the book also discusses other genres of music, like jazz, pop, folk, and Americana.

I wrote the book and talked with my interviewees in the manner all of us speak to each other, avoiding technical musical language, which, in any event, is mostly unknown to me.

That is the primary reason why you should purchase the book. There are several others.

Another is to meet the composers and players in their own words. You will find out they are regular folks just like you, and speak as you do. It is said that reading my stories drawn from my interviews is like being in the same room with me and my subject. You will be present at each conversation I have had with these twenty-one famous musicians, and discover the fascinating history of music, the history of each musician, the multiplicity of subjects in these conversations, and most important of all, how easy it is to listen to and love classical music.

The quality of those meetings can be seen in the handwritten letters on the back cover written to me by five of America’s most honored composers appearing in this book, praising me on getting deep into their psyches. Handwritten! Wow! Humbling? Yes. Inspiring? Yes. Best of all, telling me I was onto something in attempting this book.

I myself didn’t listen until I was around thirty, quickly became a fan simply by attending concerts, listening at home, and reading the programs. Never did I think I would write a book on music. As the decades went by, I became sort of an amateur musicologist, as well as an author and historian. Only then did I see this opportunity to share my experience with you.

I’m a great believer in the old maxim that a picture is worth a thousand words. You will be happy to view all fifty-five full page illustrations (photos, paintings, drawings, and caricatures) of the interviewee musicians, and famous composers and instrumentalists of today and yesteryear who are their muses.

These qualities of which I speak also expand the book into a tool for learning in many courses taught all the way from grade school to advanced college courses. One might say it is a book for all seasons. One look at the index with its close to 2,500 entries will demonstrate the multiplicity of subjects openly and clearly discussed in these pages.

A big reason to buy it is that it is a terrific gift for a person of any age. Children will understand it. Students will understand it. Your grandparents will understand it. You will understand it. When you pick up this book, whether in hard or soft cover, you will note how beautifully it is produced inside and out. A lot of hard work and expense went into that, so that its important message could be conveyed in a beautiful package, so to speak, to take its place in your library.

Music existed on earth millions of years before man appeared. Music will continue to exist on earth for millions of years after man ceases to exist. Some say music is life. I believe that. So might you to your everlasting pleasure if you allow yourself to be drawn to it in all its forms. It is my belief that this book will take you down that path.

Matt Sutherland