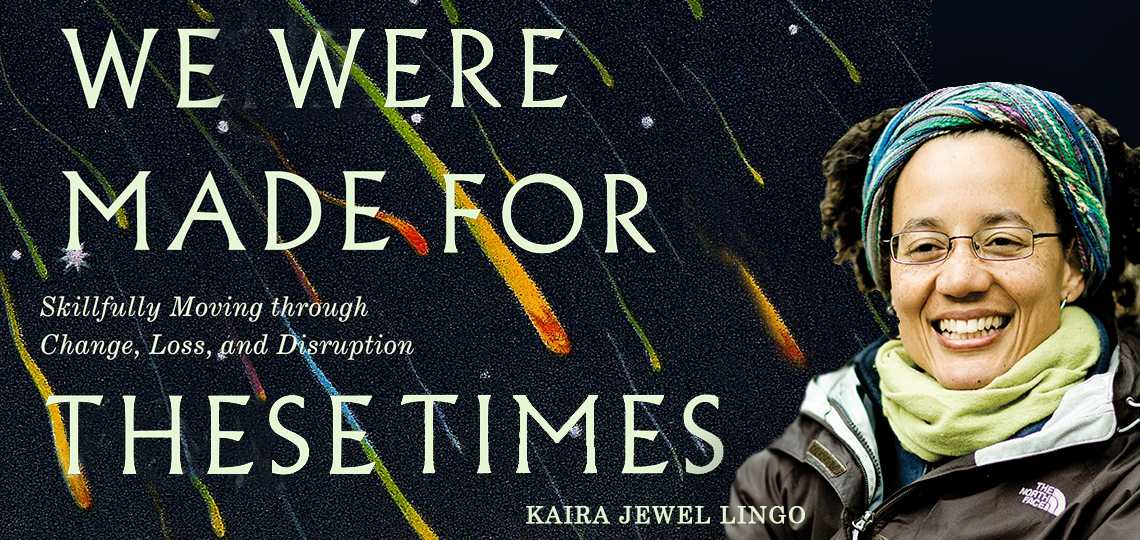

Matt Sutherland Interviews Kaira Jewel Lingo, Author of We Were Made for These Times: Skillfully Moving through Change, Loss, and Disruption

We’re blessed as a species—no need to play the fight or flight game anymore, food arrives at our doorsteps minutes after we make the request, disease is mostly understood and cured with medicine—but that doesn’t mean life is easy or free of pain.

In fact, our relative leisure time seems to have mental health implications. We’re often stressed. Our brains race uncontrollably. We worry and fret for no good reason.

Thankfully, we don’t have to live this way—if we’re willing to practice the mindfulness techniques developed by Buddhist masters over thousands of years. Meet Kaira Jewel Lingo, a Buddhist nun who trained for fifteen years under the tutelage of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh. Kaira’s We Were Made for These Times offers just the sort of down-to-earth wisdom needed to manage the major issues of the day with calm and perspective.

After a careful study of her wonderful book, we recently caught up with Kaira to ask a few follow up questions. Enjoy.

You spent fifteen years as a nun with Thich Nhat Hanh, as holy and revered as any spiritual leader we have on this Earth. What was that experience like?

I definitely would and could not be who I am without having met this amazing teacher. I am so grateful for the opportunity to learn from someone who really walked his talk and who was extremely wise and loving. I felt his main wish was for each of us to manifest our full potential as his disciples. He was extremely encouraging of his students and went to great lengths to understand our unique backgrounds so he could guide us appropriately (we ranged in age from young teens to elderly, from all over the world, of many races, cultures, sexual orientations, life experiences and circumstances). I was often amazed at how good he was at making me and us feel deeply loved and seen. I experienced him showering us with compassion, loving words, and profoundly tender regard. He was very motherly and nurturing. And when he needed to be strong and take out the pruning shears, he could also be a very tough Zen master and let us know where we were off in our thinking or behavior. But he was never forceful, or coercive. He was so full of joy, kindness, and passion for spiritual practice that we were inspired to follow him, not out of fear or just blind belief. We followed his teachings because they worked! We saw he was a happy person and we wanted to be happy like him.

He was also extremely disciplined. For instance, he always emphasized the importance of walking mindfully, putting 100% of our attention into our steps, and I never observed him walking any other way. He would not walk and talk at the same time. If he was walking with someone and they began speaking with him, he would stop walking and converse and then continue to walk again in silence so he could be fully present in his steps. He reminded us often to do the same and even with a great deal of social support around me in the monastery, it still was not easy. He made walking in peace and stability a priority and sometimes it felt to me that he was floating he moved so gracefully and elegantly.

Despite his world-renown and being enormously respected by leaders of all faiths and backgrounds, he remained humble and full of gratitude for his students. I remember one time in a ceremony to mark the annual three-month rain’s retreat, he prostrated, or bowed down to us, his students, in a moment where we would usually bow down to him. He expressed his gratitude for us, saying he could not be who he is without each of us. Then he asked for our forgiveness of his unskillfulness and vowed to continue to practice deeply so he could bring more happiness to the community. I was so moved to witness his humility and transparency in this way.

He poured out all of himself to train and guide his students. We were his priority.

Your book title points to the trying times we find ourselves in. What message can readers expect to find in We Were Made for These Times?

This book comes out of lessons that I learned from Thich Nhat Hanh, other teachers, and from my own life, and that I put into practice in my own times of difficulty and transition. The material for this book was originally offered as an online course and came out right before the pandemic. It was very timely for the many people struggling with the unexpected changes and losses forced on them with lockdowns, isolation from family and friends, losing jobs, facing illness, losing loved ones and the simultaneous crises of climate, racial and economic injustice. I received hundreds of messages describing how this course was helping people to find inner balance and stability in the face of difficulty and the multiple pandemics our world is encountering.

People testified that because of the course they were learning not to resist or fight the unwanted or unforeseen circumstances of their lives and more easily make peace with their situations. They shared that the course helped them to sit with the discomfort, and rest back in a state of not knowing which opened new possibilities and ways to move forward. They were also able to connect their personal struggles to larger, collective struggles and not feel so alone. Hearing so many people’s feedback on how the course supported them through difficult times is what made me want to make a book based on the online course.

My deepest wish is that this book can assist people as they navigate the many transitions and pandemics that our world is facing right now–be they individual or collective struggles.

Before you left monastic life, you struggled with the decision to leave until you let yourself “hang out in the space of not-knowing,” and realized it offered “enormous potential [where] life could unfold in innumerable ways.” How did you learn “the ability to dwell more and more comfortably in the experience of not-knowing.”?

This decision to leave the monastery was one of the scariest and most challenging I have every faced. I was leaving what was safe, supportive, and known and moving into something completely unknown and where I had no idea who I would become. In the stillness and silence, as the swirling of worries and projecting into the future began to slow down, I realized there were things I couldn’t control and couldn’t know about what was to come. I began to get curious about what that state felt like–the place of being in between, in limbo, not quite this anymore, but also not yet that. I stopped resisting the experience of things falling apart and learned more and more to just stay with the discomfort of it, the awkwardness of not really knowing who I was anymore. I developed more trust in what was unfolding in my daily life because I saw that even if I didn’t have control, I was somehow still cared for. I really took care not to try to make important decisions too quickly, if I was still unsure. This slowing down allowed me to notice the worry, longing, and fear of the future and be with it in the present rather than letting it take hold of me and drive me. Instead, as I sat with all the emotions, allowing them to be, I touched a part of me that was undisturbed, beneath all the turmoil. Knowing I could be undisturbed in the midst of one of the biggest transitions, or disturbances, of my life helped me to rest back and trust the process, even if I didn’t know where it would lead me.

Please explain how mindfulness can help us work through bouts of anxiety, anger, and other strong emotions?

Our usual approach is that we either allow our strong emotions to take us over or we repress, avoid, or deny them. Mindfulness helps us to recognize strong emotions, so we can turn toward them with our full presence and take care of them. We give them space to be, but we hold them with awareness so they cannot cause damage. Mindfulness is like a kind parent and our strong emotions are like a crying baby that needs care, not punishment or judgment, and they also do not need to be left alone and ignored.

When we turn toward our strong emotions, willing to be with them, even though they are painful, we offer them acceptance and they begin to settle down, just as a crying child does in the arms of a loving caregiver. Then we can look deeply into our emotion to understand it better and see how it has come to be. This helps us gradually become more and more free of the power that emotion has over us. It can still arise, but with mindfulness we have the space to choose how to relate to it with kindness and skillfulness, rather than reactivity.

In one of your meditation practices, you ask readers to recognize the truth of impermanence by facing the things we normally don’t want to see. Why is it important to confront reality in such an active, day-to-day way?

It is important to face the truth that the things we hold dear: people, animals, homes, land, social structures and systems, are of the nature to change and we can’t avoid being separated from them because otherwise we can remain in a trance, taking them for granted and living on the surface of our lives. Just like when we get a whiff of the brisk, chilly air of fall it clears our mind, getting a whiff of the brisk truth of impermanence clears our mind of illusions that we and others in our life will be around forever and that what is on our “to do” list is more important than how we interact with them.

Many of us live in ways that sacrifice the present moment for the sake of the future. But the future is made of the present moment. Confronting the reality that we really don’t know how long our lives or anyone else’s will be supports us to be present for the gift of each moment that we have to breathe, to feel, to connect, to look into another’s eyes and be truly present for them. Consciously getting in touch with impermanence on a regular basis helps us to become fully alive so that when it is time for us or those we love to die, we can face this transition without regret, knowing we did not miss precious opportunities to develop our own heart and mind and to grow in compassion and understanding for others. Caring deeply for the present is the best way to care for the future. Staying awake to impermanence supports us to care for the present moment.

For those readers who may be intimidated by meditation, can you offer a definition of meditation, as well as a simple explanation for why your book makes such important use of meditation practices as a tool?

Meditation is bringing your mind into the present moment, to experientially know what is happening at the level of your body, your emotions, and your thoughts, because then you become more intimate with yourself and can have some influence over what would otherwise be run by your reactivity and habit. Meditation in general, and the meditations I share in each chapter of my book, can lead to profound healing and developing of the inner resources of wisdom, clarity, peace, freedom, and joy that are sorely needed in the world right now.

We can put our attention anywhere and so often where we end up putting our attention is not helpful to us and causes us to be overwhelmed by worry, anxiety, discontent, and stress. The meditations in my book help you learn to harness the awesome power of your attention to benefit you—mentally, physically, relationally, and spiritually, by putting your attention on what is actually occurring moment-to-moment and tapping into the quality of open-hearted awareness that is always available to us, no matter the external circumstances. It is one thing to read about a practice of coming home to yourself or accepting the difficulties in your life, it is a very different thing to experientially touch, through meditation, coming home to yourself and accepting the challenges in your life, so you have more spaciousness, more ease. Meditation helps us taste these healing and powerful states for ourselves. When we experience them in meditation, they ripple out into our lives, transforming our way of being.

Matt Sutherland