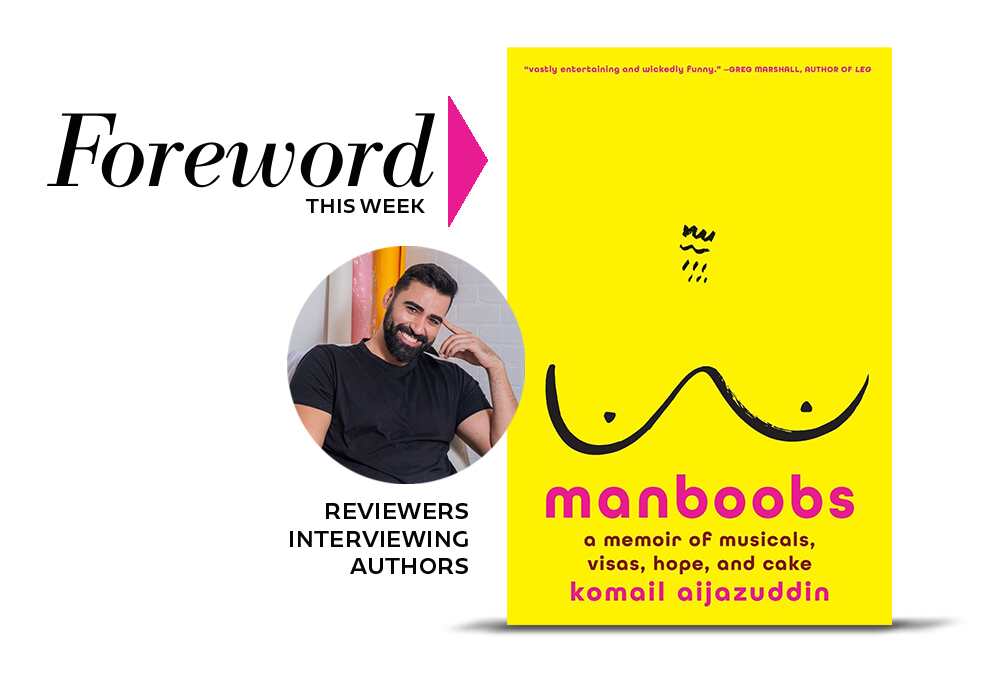

Meet the Larger-than-Life Komail Aijazuddin, Author of Manboobs: A Memoir of Musicals, Visa, Hope, and Cake

“The truth about the American Dream is that you have to be asleep to believe it.’’ —Komail Aijazuddin

Pakistani American Komail Aijazuddin first charmed his way into our hearts with Kristine Morris’s starred review of Manboobs in the Memoir feature in Foreword’s July/August 2024 issue.

Funny, irreverent, and blessed with what Kristine describes as a “kind of sixth sense that makes inner worlds perceptible,” Komail is everything we look for in a memoirist—can you blame us for wanting to keep him in the Foreword fold long enough for the following reviewer-author conversation?

(Check out the other four books in that spread here and then nab your free digital subscription to Foreword Reviews here.)

You dedicated your book to its readers, saying: “I dedicate this book to you, with the hope that in reading my story you may find the strength to tell your own.” And this seems to me to be one of the powers of story and a particular gift of your book—that through your openness in sharing your challenges and joys others may see that they too can be strong, authentic, and true to themselves and thrive. What drew you to tell your story at this time?

Thank you! I’ve been working as an artist and writer for nearly two decades, but as I grew into my career, I noticed there were vast, important areas of my life—sexuality, religion, body dysmorphia—that I wasn’t talking about in my work or life. Despite having been an out queer person since I was seventeen, it felt as if I had sequestered vital bits of me behind a wall, dank and dark, because it wasn’t always safe to be myself, but also because queer people often feel it’s ok to diminish ourselves for the sake of others. That kind of self-erasure is untenable for anyone, artist or not, and I felt the need to this write book to bring light to all the parts of me that I was afraid to let shine. In that sense, all art is an act of courage.

The imagery in your prose reflects an amazing attention not only to what can be seen with the eyes, but also to what can be perceived only with a kind of sixth sense that makes inner worlds perceptible. You knew, even as a child, that you were different: gay and obviously effeminate, overweight and body-dysmorphic, bullied for being a minority Shia Muslim, and sports-averse in an all-boys school obsessed with them. What is there about you that helped you cope with growing up in a society and culture that told you that you were all wrong?

Cheesecake mostly. I was, as you point out, a conspicuously overweight and effeminate boy obsessed with recreating Evita’s balcony scene in an all-boys school that felt like the first season of a prison drama. So it’s safe to say I stuck out. Part of what helped me survive was being able to escape into the comforting world of books, pop culture, and comic books, since those spaces too were filled with bitter outsiders plotting intricate long-term revenge fantasies.

The title of your book relates to a certain physical characteristic, gynecomastia (enlargement of breast tissue in males), that together with body dysmorphia and obesity (the result of a tendency to seek comfort in food) caused you a lot of emotional distress throughout your growing up years. What might you now say to other young men dealing with serious body-image issues?

The short answer is structured jackets, but the longer answer is to be radically kind to yourself. You’re in charge of how you feel about your body, no one else. Not parents, spouses, friends, lovers, or strangers. When your brain tells you to be insecure about your nose or love handles or thighs or even manboobs, please remember that everyone (even that one fitness instructor on Instagram whose closest adult relationship appears to be with a box of prescription strength laxatives) is insecure about something.

The best way I know to combat those intrusive thoughts is to remember that self-acceptance is not a destination—it doesn’t magically materialize after reaching your goal weight or getting visible abs or running a marathon or finding a mate. It comes from repeatedly reminding yourself, hundreds of times a day if necessary, that the cruel voice in your head telling you are not good enough as you are is just that—a voice. It is not a fact—it is not the truth. What is a fact is that happiness comes from accepting yourself—first as you are now, and then walking towards what you hope you could be.

Early in the book, you wrote that you grew up being told that you were “too gay to be Pakistani” and felt drawn to the US, touted by movies and television as holding the answers to all your questions, only to find that in America you were “too Pakistani to be gay.” Looking back at that time in your life, what were your expectations in moving to New York? How were they met? In what ways were they unmet? How did you cope with the feeling that you might never be able to live and love authentically no matter where in the world you made your home?

My expectation was inclusion, which is one of the promises of immigration in general but also integral to the myth of the American Dream that the US exports so constantly to the world through its culture. But, as I wrote in the book, the truth about the American Dream is that you have to be asleep to believe it. I naively assumed that simply arriving in America would mean I’d seamlessly integrate into the queer world here. But the early 2000s were an ambivalent time for queerness, and America after 9/11 was not a welcoming place, whether one was queer or not. I realized quickly that I was a brown foreigner here before anything else, and given that a global gay identity is often sewn together with local American culture, the discovery was depressing enough that I bought full fat ice cream.

The US has been marked by a series of deeply traumatic events, including the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, economic turmoil, a pandemic that brought isolation, mass sickness and death, and now a polarizing election process. How have these events affected you and your work?

The most immediate effect of being a Muslim male during the years of the “War on Terror” was that a constant performance of gratitude was expected of me. “Thank you,” my smile was designed to convey: thank you for letting me in, thank you for making an exception, thank you for not hating me on sight—that’s so “Freedom” of you.

With the world as chaotic as it is, and your work so revelatory of who you are, what do you do to stay safe in Pakistan and in New York?

Meditation and anti-depressants. Writing the book for the past eight years was such a personal experience of catharsis that part of me forgot that people would eventually read it. But I’ve spent the last twenty years thinking deeply about all the things in this book, and I wanted—no, needed—to share what I had learned if only to help anyone else going through a similar struggle. Whenever I get too overwhelmed with the anxiety of what could happen, I remember that I am not wrong simply for existing. No one is, but the world is very good at convincing you otherwise.

Your book relates some scary encounters, close calls, and hilarious events. Please tell our readers about a few of these situations and how you dealt with them.

It’s a funny book about growing up gay and overweight in Pakistan and the US told through the lens of American pop culture, but it’s more than just a story about trauma and carbs. There are too many instances to detail here, but people will read about blasphemy charges, German stalkers, Greek sex gods, spy agencies, exorcisms, witchcraft, Ramadan, and that one time I had to get rid of a (mostly) dead body. I promise them they’ve never read anything like it.

What do you see as the role of the artist and his/her work in the world?

I define an artist as a person who processes their lived experience in public so others might do it in private.

Please tell our readers about your painting process. What inspires you? How would you describe your work? How is it being received in Pakistan? How is it received in the US?

I work out of my studio in Brooklyn, mostly in painting, drawing, and installation. I use a lot of gold leaf in my work, a vestige from my early interest in religious art, and currently have been making pieces that explore the flamboyance of a gay childhood. You can find more of my art on Instagram@komailaijazuddin or on my website: www.komailaijazuddin.com.

Your prose sparkles and dances on the page! Tell us something about your writing process, please. What place does writing hold in your life?

That’s very kind of you to say. I’ve always written with the voice in the book, which is probably the reason I made a very bad journalist. Writing is the closest thing to truth I can achieve.

What message would you most like readers to take with them from reading your book?

I hope that it makes them laugh, I hope that it makes them think, and I hope they recommend it to their book club.

Do you have another book or exhibition of your paintings planned? What do you see opening up for you in the future?

I recently was in a show in LA and I’m working on some projects in both writing and painting, but until the book comes out my main focus is on getting beautiful people with great eyebrows and intelligent hearts such as yourself to consider buying a copy of Manboobs.

Kristine Morris