Memoirs: Step into the Mind of Another

It’s easy to miss what’s going on in someone else’s world. You don’t have to be a narcissist to get lost inside your own head. But this makes it more urgent to seek out experience beyond our own. These biographies and memoirs, reviewed in our March/April issue, allow you to step into another’s world and experience it through their eyes, their experiences, their cultures. Enjoy and learn.

Cancer Is Funny

Keeping Faith in Stage-Serious Chemo

Jason Micheli

Fortress Press

Hardcover $24.99 (189pp)

978-1-5064-0847-7

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

In this pastor’s memoir, humor is shown to be a critical part of faith and of confronting health challenges.

In the Rev. Jason Micheli’s memoir, cancer is both funny ha-ha and funny strange. Diagnosed with a “stage serious” rare bone cancer, Micheli faced the ravaging of his body, family, and faith—certainly not the normal fodder for humor. Except that it is. Micheli found that in the depths of a disease, where one is laid most bare, the opportunity and the necessity for humor arise and align with the belief that God is joy, and joy involves laughter.

Micheli relates how, in the minds of others, cancer stripped away his humor; people assumed that, because he was a clergyman, his faith alone would sustain him. He found himself cast as a solitary and pious figure, thought to be incapable of the ribald humor he displays. This book breaks that impression, recasting him as a person capable of doubt, one with both warmth and humanity—who writes, for example, of a drill going into bone for marrow, that it feels “like a Harry Potter Dementor sucking my soul out of me through my ass.”

Chapters generally begin with an anecdote: his initial diagnosis; his interactions with doctors and nurses; his relationship with his family. These stories are followed by Bible stories, which Micheli approaches with greater understanding in the long, tedious days of his physical infirmity; he relates how he achieved new clarity in the wake of his illness.

Micheli’s Bible explorations are intimately connected with his lived experience. In the pursuit of understanding, he makes points through logical, accessible argumentation that is never divorced from humor or doubt. His voice is honest, wry, and calm, and his work is particularly powerful in its relatability. His biblical explorations do not force particular ideas or assumptions about faith so much as they ask the reader to ponder questions themselves.

“Persisting with God, even when you don’t feel God, is the exact definition of faith,” Micheli concludes. This is no spoiler; the remarkable thing about this journey is found in Micheli’s ability to laugh and love along the way.

CAMILLE-YVETTE WELSCH (January 27, 2017)

Dancing on a Powder Keg

The Intimate Voice of a Young Mother and Author, Her Letters Composed in The Lengthening Shadow of Hitler’s Third Reich, Her Poems from the Theresienstadt Ghetto

Ilse Weber

Michal Schwartz, translator

Bunim & Bannigan

Hardcover $34.95 (340pp)

978-1-933480-39-8

Buy: Amazon

This sobering, respectful collection brings a haunting legacy out of the viciousness of the war.

Dancing on a Powder Keg elucidates one Jewish woman’s experience in Czechoslovakia during the Holocaust. Translated from the German by Michal Schwartz, Ilse Weber’s brave reflections reveal the effort to keep artistic practice alive while raising young children in dark times. Historic, unsettling, and beautifully composed, these writings add a crucial note to existing scholarship on the Holocaust.

A writer for radio, lyricist, children’s book author, and later a nurse on the children’s ward at the Theresienstadt concentration camp (which was also called the Theresienstadt Ghetto), Weber turns everyday events into lively descriptions through letters that span 1933–1944. The majority are written to Weber’s friend in England, Lilian; Lilian’s mother, Gertrude, who sheltered Weber’s eldest son in Sweden during the war; and to her son. Germany’s growing threat is drawn through mentions of scarce finances, the plights of friends, pogroms, and divisions among the Czech people, and all while Weber persisted with household duties. Affectionate portraits of her children rapidly give way to accounts of anti-Semitism and fear. In the absence of Lilian’s replies, these letters become a personal record of losing freedom and keeping faith. Questions linger unanswered. They build with urgency, turn briefer and rarer, then suddenly cease.

A useful note by Ruth Bondy on Theresienstadt and an afterword by Ulrike Migdal provide background. Biographical details and the story of how Weber’s writings were preserved add necessary context. The account of her surviving son, Hanuš, is particularly fine. It balances between the tragedy of a young son who was separated from his family—and who, at the time, remained unaware of their ordeal in the camps—and the adult who later learned the truth. It’s here, in the unspoken weight of such knowledge, that the full impact of Weber’s death comes to rest.

Weber was known for her compassion toward children in the camp. Her lullabies and poetry portray their longing with staunch intelligence. Spare images depict the pain of imprisonment and horror of transports even as they hope for an end to suffering. This sobering, respectful collection brings a haunting legacy out of the viciousness of the war.

KAREN RIGBY (January 27, 2017)

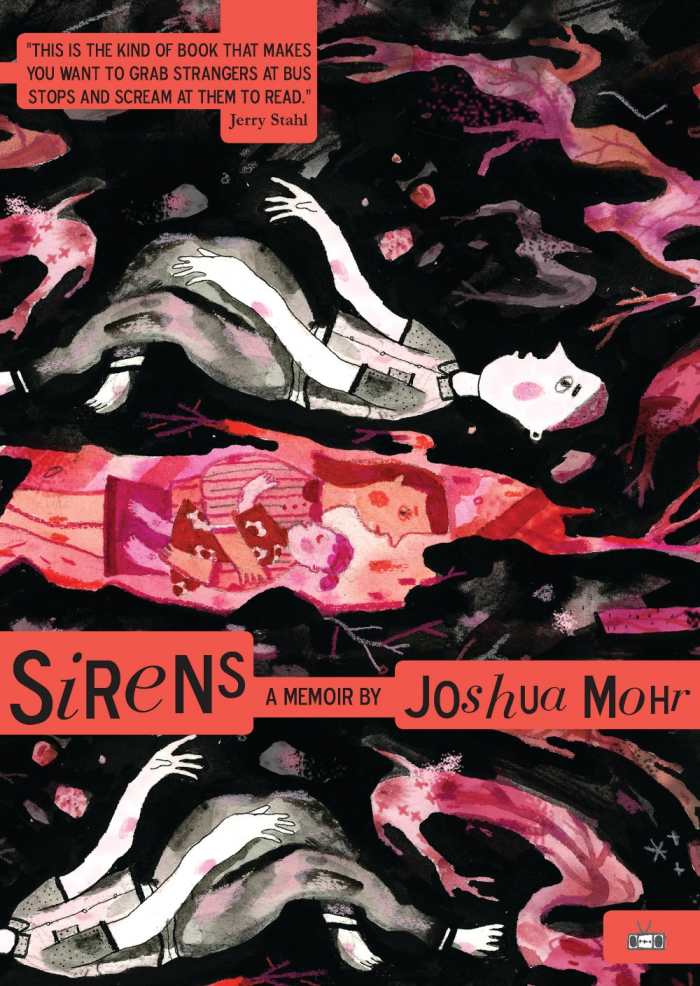

Sirens

Joshua Mohr

Two Dollar Radio

Softcover $15.99 (208pp)

978-1-937512-34-7

Buy: Amazon

Sirens is a dark, urgent, and brutal picture of addiction—but also one that shows that recovery is possible, even if it is a lifelong pursuit.

Joshua Mohr’s memoir Sirens plumbs the raw wounds and high hopes of addiction and sobriety. This is a revelatory narrative, as fascinating and disturbing as it is necessary.

In relating his young adulthood of addiction, relapse, and eventual, tenuous sobriety, Mohr opts for the uncut truth. Those who have been there before are likely to cringe with recognition: family visits with shocked relatives after all-nighters; tumbles through the city on benders; weekend-long blackouts following the ingestion of unknown substances from strangers. Mohr, in his youth, was called to it all, chasing the music of a perpetual high right onto the rocks. His depictions are graphic, self-aware, and refrain from making convenient excuses.

So, too, are beloved people omnipresent: friends and fellow users he tried to do right by; a first wife whose ultimatum he rejected, and a second whom he subjected to the roller-coaster for longer than he is proud of. He speaks of those he loves with shame, awe, and respect, and it is they—particularly his daughter, Ava—who finally prompt him to seek change. His memoir is self-referential as it details his fears in the midst of sobriety: that he will relapse; that he will let his daughter down; that even the anesthetic that he needs before heart surgery could prove seductive enough to send him hurtling back. For Ava, he presses on. For Ava, he leaves no dark secret unrevealed.

Even when its pages are a “pageant of debasement,” Mohr’s work captivates, chronicling the desperate need that addicts feel, their inventive methods of self-sabotage, and the reality that falls off of the wagon are rarely gentle affairs. His is a precarious disease, and his intricate account shows just how vigilant one must be to hold it in remission. Sirens is a dark, urgent, and brutal picture of addiction—but also one that shows that recovery is possible, even if it is a lifelong pursuit.

MICHELLE ANNE SCHINGLER (January 27, 2017)

A Mother’s Tale

Phillip Lopate

The Ohio State University Press

Hardcover $24.95 (196pp)

978-0-8142-1331-5

Buy: Local Bookstore (Bookshop), Amazon

Lopate’s stories of his mother paint a rather bleak portrait of the dark side of the American dream.

Phillip Lopate’s A Mother’s Tale reveals the author’s complex relationship with his mother, Frances, through essays that show vividly her harsh life and struggles to overcome economic and social obstacles confronted by most women whose lives spanned the twentieth century.

Lopate directs Columbia University’s nonfiction MFA program and has written sixteen previous books, and this one further burnishes his reputation as a highly regarded essayist. These essays are based on tape recordings with his mother in 1984, when Frances was sixty-six and Phillip was forty-one. What makes the dialogue memorable is the explicit, no-holds-barred banter between the two. Francis graphically describes her unfulfilling sex life with her husband, Albert, and details her numerous affairs, not usually shared between a mother and son.

This is not a happy, feel-good memoir, as son and mother grapple to come to terms with their estrangement; before Frances died in 2000, she, Phillip, and Albert each attempted suicide. Readers will empathize with Frances, whose parents died before she was ten. One of eleven children, she was shuttled among unloving siblings. Frances, always career oriented, found some success as a beautician and in running two candy stores and photography studios, and she found joy in her true love—show business—mostly touring in plays and even making a few TV commercials.

The dialogue, recreated from thirty-year-old tapes, is fresh and gripping but, at times, difficult to follow because the speaker is not identified. Lopate claims that the essays are discussions among three people: Frances and the author as both a middle-age man and a seventy-three-year-old man, his age when he wrote the book. Readers might disagree with Lopate’s premise that the attitudes of men or women at these ages vary and result in a different interpretation of the subject.

Lopate’s stories of his mother and her relationship to the author and his family, which paint a rather bleak portrait of the dark side of the American dream, will appeal to devotees of coming-of-age memoirs.

KARL HELICHER (January 31, 2017)

Hannah Hohman