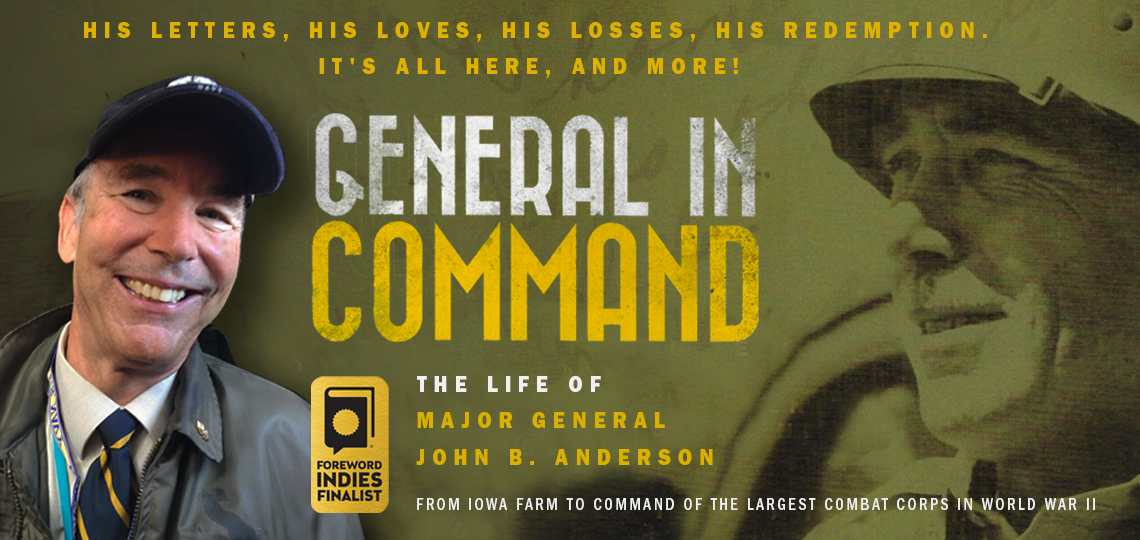

Michael Van Ness Talks about His New Biography of WWII General John Anderson, General in Command

War is hell, we are told, but most of us don’t really know. And that’s why it’s vital for us to honor the men and women who fought and sometimes died to defend this nation. Beyond paying our respects, we should also strive to know the hell that is war so that we do everything in our power to avoid it in the future.

Looking back on conflicts of yore, World War Two stands out for its unfathomable destruction: seventy-five million dead. To better understand this particular war’s hellishness, we can now turn to Michael Van Ness’s General in Command to experience it through the eyes of a humble US commander, Van Ness’s grandfather, General John Anderson. A veteran himself, Van Ness inherited the general’s war years diary and letters. For two years, he immersed himself in research and writing, and the resulting book provides an intimate glimpse of Anderson’s wartime state of mind.

In his review for Foreword’s Clarion review service, Benjamin Welton calls the book a “fascinating biography of an overlooked but great American soldier.” Seeking to learn more about Anderson and the war to end all wars, we put Welton in touch with Van Ness for this conversation.

Gentlemen, take it from here.

The first and most obvious question for all prospective readers is: Why General Anderson? What made you decide to cover this little known American general?

As a six-year-old boy, I would often stare at a black-and-white photograph hanging in the back hall of their modest colonial home in Northwest Washington. There was my grandfather; he was with Winston Churchill.

As a six-year-old, I didn’t really know enough to ask many questions. And even as a young man, I was too self-absorbed and self-involved, but now, as an older man, I would like nothing more than to have a word with my grandfather about what life was like as a general officer in World War II. He was a Forrest Gump-like character rubbing elbows with the military greats of the first half of the twentieth century. A 1914 West Point graduate, he served on the Texas-Mexico border with General John Pershing. When Pershing took the First Division to France in the summer of 1917, Captain Anderson, as a member of the US Sixth Field Artillery, went along.

Anderson was present when the first shots were fired into the German lines by the field artillery. Later he served as a liaison officer with the British, in Flanders, near Ypres.

Since I had served in the military myself, I had possession of all his uniforms, medals, pistol, and most importantly, his World War I diary and all his letters to family in the interwar years and during World War II. This primary source material gave me a good insight into his state of mind before, during, and after the Second World War.

Do you think that he represents a type—an American archetype, for lack of a better word?

One of the things that struck me was his modesty. He was the youngest child of Danish immigrants who came to this country in 1872. His mother was forty-seven years old when she bore him in Parkersburg, Iowa. He grew up on a farm and by virtue of his experience with farm animals, he was caretaker of the Army mule during the 1913 Army-Navy game. In addition, at West Point, he organized the First Class Cavalry ride in anticipation of graduation. The point being, he was a farm boy. He had no connections, and his career was based on academic achievement and leading men in battle.

So he is an American archetype—a self-made man who, through hard work, accomplished a great many things. He also had significant losses in his life. When he was a sophomore at West Point, his mother died. As he left to go to France in World War I, his first wife divorced him. That same year, his father died. So the Army was his life.

Because the Army was his life, he did not cultivate outside interests. When he retired at the end of World War II, he had little to fall back onto except his second wife and his only child, my mother. My mother pointed out that she was reminded of her father whenever she heard the song What Do You Do With A General When He’s No Longer A General from the movie White Christmas. In addition, his alcohol abuse accelerated as his social isolation settled in.

Besides his quiet, unassuming demeanor, why do you think so many historians have overlooked Major General Anderson? Why is his name so often forgotten by military historians?

That’s a good question. There were only thirty-four Corps Commanders in the field during World War II. Because of his unassuming nature, I don’t think he fought for himself nor did he engage in any sort of self-promotion.

For Anderson, the Rhine River crossing was the culmination of his life’s work. It also was a moment of great danger for him. The British wanted to create the impression that they were the ones primarily responsible for winning the war. The photograph of Anderson with Winston Churchill was the result.

Eisenhower was furious that Anderson had exposed Winston Churchill to danger on the Rhine River. More importantly Eisenhower was furious that he and Bradley were not present to share in the good publicity. In fact, Eisenhower was off spending a long weekend in Paris with his mistress, Kay Summersby. I can only imagine that Eisenhower was furious not only for the missed publicity opportunity but also the potential embarrassment of having to explain to his wife, Mamie, why he wasn’t there.

In truth, some of this is speculation on my part, but the Army was a very small community in those days. All the generals knew one another. Anderson was one year ahead of Eisenhower at West Point. Eisenhower and George Patton had been in school together for years. Patton had served on the Texas-Mexico border with Pershing. The point being, although there’s no documentation that Eisenhower was personally embarrassed or angry with Anderson, the fact of the matter is that Anderson was denied the promotion commensurate with his duties in combat.

How long did it take for you to research this book? What was the most shocking discovery that you unearthed during the research?

It took me two years to do the research and write the book. The photographs in the book are from my grandfather’s personal collection. Two things surprised me in my efforts. First, the United States likely committed war crimes in its treatment of German prisoners. The conditions in the Rhineland camps were appalling. The Allies failed to follow the Geneva Convention. Second, the contribution of African American troops was appreciated at the time, much more than the history books reflect now. Anderson went to great lengths to recognize those efforts. Lastly, post-traumatic stress disorder is not new. Anderson bore the invisible scars of wounds inflicted in battle for the rest of his life.

What would you say to non-historians or students of World War II about the Rhineland Campaign? Why was this campaign so integral to the Allied victory in 1945?

The Rhineland campaign was the finest example of American and British military cooperation of the war. The senior ground commanders used every tool at their disposal to minimize casualties and to achieve their goals. They succeeded. It is the perfect example of the truth of the expression, “The only thing worse than allies, is no allies.” Politics was a secondary concern to the men on the ground. The fact is the military leaders acted professionally, true to their calling, and had great success against their common enemy.

Any plans for more biographies in the future? Any more books on the horizon?

I do have a book entitled Ike and Andy in the works. Another six to nine months I would say. In this book, I will further investigate the relationship between Dwight Eisenhower and John Anderson. In particular, I want to explore the deterioration of their friendship from West Point through the war years, and the fact that they both lived in Washington, DC, for most of the 1950s and never had any contact, personal or professional.

Benjamin Welton