On Writing A Memoir in Real Time

During the year that my husband and I spent planning a lengthy French sojourn, I envisioned writing a book about the forces that converge to force baby boomers out of traditional work arrangements sooner than expected—something that had happened to both of us. Ken had been sidelined by back problems and a profound hearing loss. I had resigned an oppressive editorial job at a place I called The Content Mill to reclaim my independence as a writer.

Deborah L. Jacobs: 'But, as so often occurs with foreign travel (and life), nothing went according to plan.'

To help pay the bills, I came up a strategy that we called living on the sharing economy. The concept was to rent our historic townhouse in Brooklyn, New York, when our only child started college and live in France on the proceeds. They could cover all of our expenses, including the rent for ninety days (the maximum time in a six-month period that we could stay in the European Union without a visa); a rental car; and food, assuming we prepared most of our own meals.

As our base, we chose the Loire Valley, about two hours southwest of Paris, where for centuries royalty built their châteaux. From a former winemaker’s cottage that we rented, in a hamlet near Amboise, I would start research for a book with the working title, Boomer Burnout: Why the driven generation is running out of steam, and how they can tackle their toughest challenge yet.

But, as so often occurs with foreign travel (and life), nothing went according to plan.

Not a Dream Cottage

Though the winemaker’s cottage, where we intended to spend the entire three months, got rave reviews online, we arrived to find the beds unmade, the cabinets filled with moldy food and a strong smell of mildew in the living room. To make matters worse, the place was such a rabbit warren that it was hard to find a comfortable spot to write. Our bedroom had a gait-leg table that I could have used as a desk, but there was no space for a chair, and I couldn’t reach it sitting beside it on the edge of the bed.

Instead, I set up my laptop in what the owners called the tower bedroom. I pulled up a chair beside the trundle bed, used its surface as a makeshift desk and admired the distant view of the Loire. The only problem was when I stood up: The sloped ceiling was so low in spots that I bumped my head at least several times a day (and I am just a little over five feet tall). In my line of work I wasn’t accustomed to needing a hard hat.

Meanwhile, in response to our strenuous e-mail complaints about the condition of the cottage, the American owners wired a refund for the balance of our rent, enabling us to leave after ten days. Somewhat shellshocked, we abandoned the idea of spending three months in one place and charted a more itinerant journey.

Our second French rental was a rambling, five-bedroom Victorian in Le Puy-Notre-Dame, a tiny Loire Valley village surrounded by vineyards. I turned the former liveryman’s quarters, with its terra-cotta floor and stenciled walls, into my office, and via Facebook updated my friends with a photo of my new workspace.

My friend Dan, responding to my post, promptly put up a link to one of Vincent van Gogh’s paintings of his bedroom in Arles—the arrangement of the furniture and placement of the window were the same, though it was Provence, not the Loire Valley, that was the subject of van Gogh’s painting. Other friends reminded me of literary legends who thrived in France, among them Honoré de Balzac, Gustave Flaubert and George Sand.

I, too, was energized, composing essays in real time about our daily activities and the emotions that accompanied this huge transition. Instead of pen and paper, I relied on the Evernote app that synced to my laptop, iPad and iPhone. That way, if I thought of something while we were out and about, I could make a note of it on my iPhone and then pull up the same material on my computer later. Just as I did as a blogger at my previous job, I gave each note a title or headline and would work on several at a time.

Book Incubation

At least a few times a week, I turned specific notes into e-mails to friends whom I thought they would interest. I didn’t do that with the expectation that any of them would reply at length, or even at all. But by then I was incubating a book, and given the quixotic nature of the undertaking, I found it less intimidating to direct my musings to specific people rather than project them into the vast unknown.

As autumn descended on the Loire Valley, we drove 500 miles south and west, to Basque Country, where we had arranged to stay in Sare, a one-street village five miles from the Spanish border. There we were tenants of Laurence and Emmanuel Chambon, owners of a 17th-century mansion that once belonged to shipbuilders. Laurence, an architect, had renovated the 11,000-square-foot house, and operated an antiques shop there. After closing the store two years earlier, she turned that space into a triplex apartment with a separate garden and entrance.

Furnished with antiques and family heirlooms, it had views of fiery fall foliage, grazing livestock and, on a clear day, La Rhune—the first summit in the Pyrenees. I created a new workspace, in the second bedroom, where there was a writing table just double the width of my laptop. We stayed with the Chambons for six weeks, as I continued the narrative with even greater intensity.

My e-mails to friends, filled with history, art and local color, painted a vivid picture of our enriching time in France. I wrote about the slower, more gracious lifestyle; how we used a cookbook to familiarize ourselves with the Basque cuisine; and the frustrations and satisfaction of communicating in a new language. Despite frequent power outages in rural France, a high-speed internet connection enabled us to manage our finances, my business and communication with our son from a distance.

After a morning of writing, I would join Ken for an excursion—walking on the beach at Biarritz or St. Jean-de-Luz, eating pintxos (the Basque word for tapas) in the Spanish city of San Sebastián, or attending one of the many autumn festivals, like one in the nearby village of Espelette celebrating the chili pepper harvest. We became regulars at the Saturday morning market in Bayonne, where we bought apple cider, root vegetables and sheep’s milk cheese from local farmers, and slurped down a plate of oysters before heading home with our haul.

Book Changes Subject

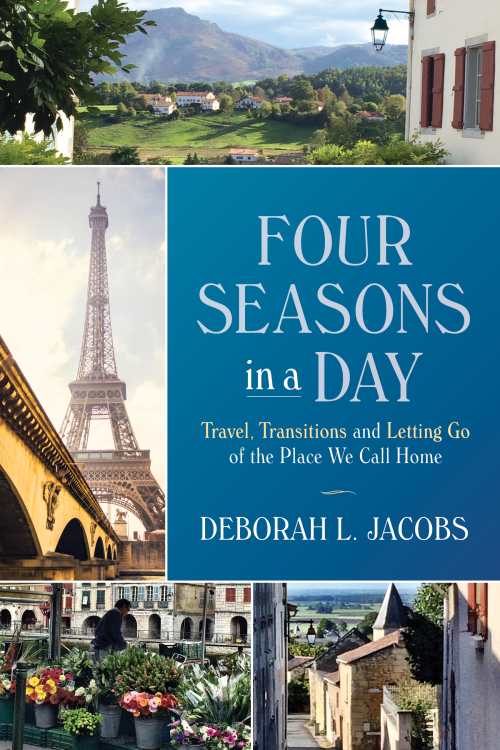

Transported to a world far beyond The Content Mill, I was no longer in the right frame of mind to tackle the subject of boomer burnout. Instead, a book about travel, transitions and letting go of the place we call home—in every sense of the word—began to take shape. I called it Four Seasons in a Day, an expression used to describe the changeable weather in the Pyrenees. In the course of my travels, endless possibilities replaced what had previously seemed like insurmountable constraints.

Still, there were moments when I worried that I was spending too much time during our French adventure writing a book on spec. I did not want to look back on this interlude and wish I had spent less of it working. But I also knew that if I didn’t write about the sights, sounds, smells and emotions as we were experiencing them, I would lose the richness of the detail. That was especially true in Paris, our final destination, and where terrorists struck Nov. 13, 2015, midway through our two-week rental.

By the time we returned to New York, I had produced about sixty e-mails, totaling about 70,000 words, and organized them into a draft table of contents. It took another year of writing, editing and rewriting to finish Four Seasons in a Day. Unlike other memoirists and travel writers, I didn’t have to rely purely on recollections. With high-tech tools I had proven the adage, “The worst pencil is better than the best memory.”

Deborah Jacobs, a journalist and indie publisher, is the author most recently of Four Seasons in a Day: Travel, Transitions and Letting Go of the Place We Call Home, from which this essay is adapted.

Deborah L. Jacobs