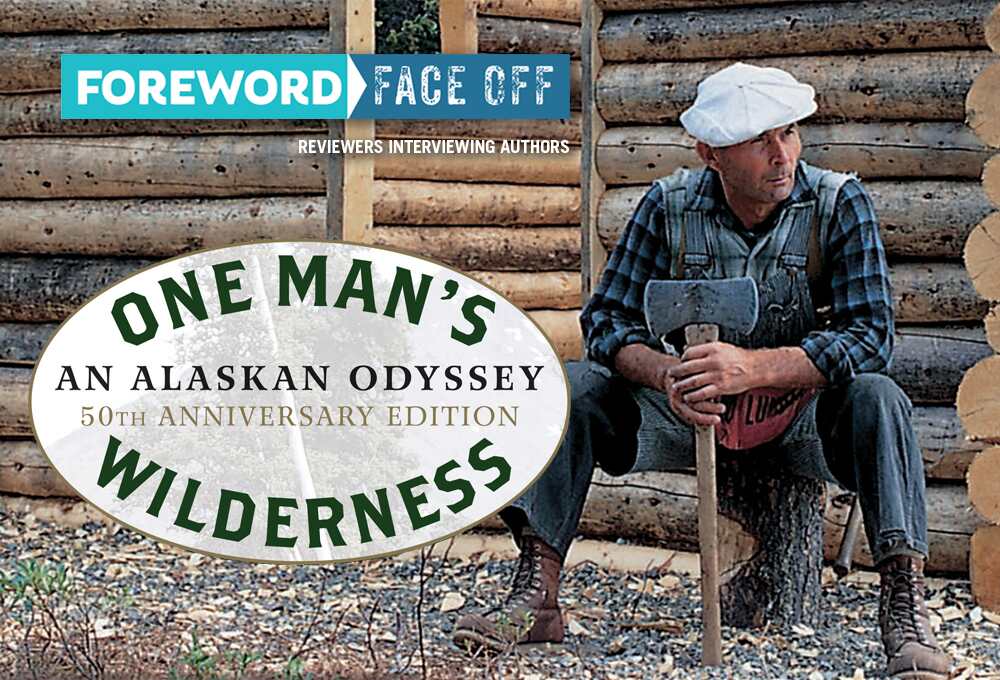

One Man's Wilderness: An Alaskan Odyssey Is Nature Writing At Its Best

Editor-in-Chief Matt Sutherland Interviews Brie Anderson, Curator of Richard L Proenneke Museum

On our deathbeds, as the candlelight flickers out after a lifetime of reading, will we flashback to the great books we’ve read? Will Jean Valjean, Jose Arcadio Buendia, Hermione Granger, and significant others appear in flashes to remind us of their unforgettable escapades in storyland?

And not just fictional characters. Certain memoirs and biographies introduced us to remarkable people, including a few books (Anne Frank’s, for example) composed of the day-to-day missives of an author’s journal. Indeed, diaries are especially powerful. There’s just something about reading mundane details interspersed with extraordinary events.

Take this July 2, 1968 entry from Dick Proenneke:

Still, with mist rising from the slopes of the mountains. Forty-five degrees. I would go up high today. After yesterday, which was the day of the lost axe, I had to take a little trip. …

I broke out into the willows that grew around the edges of the cotton-woods. There were no fresh moose droppings or tracks. But then I came to a clump of cow parsnips freshly cropped and the grasses mashed around them. Funny, I thought, I have never known a moose to eat this plant. I looked about. The leaves of the cottonwoods quivered against the sky. Suddenly the brush to my right rustled and crashed. I spun, expecting to see the bull getting up out of his bunk—and every hair on my head stabbed electricity into my skull.

A huge brown bear was coming head on, bounding through the willow clumps not fifty feet away! His head looked as broad as a bulldozer blade. I threw up my arms and yelled. That was all I could think to do.

On he came, and I thought, ’At last you’ve done it, nothing can save you now.’ I was stumbling as I retreated in terror, shouting.

I tripped and fell on my back. Instinctively I started kicking at the great broad head as it burst through the willow leaves. And then as he loomed over me, a strange thing happened. The air whooshed out of him as he switched ends. Off he went up the slope, bunching his huge bulk, climbing hard, and showering stones. Not once did he look back.

That, dear reader, is an image I’d be happy to recollect on my deathbed. Without a doubt, Dick Proenneke’s One Man’s Wilderness: An Alaskan Odyssey is as memorable and captivating as any I’ve read in my five decades of reading. Thanks to Alaska Northwest Books for reissuing this 50th Anniversary Edition and turning on a whole new generation of readers to the tale of Proenneke’s eighteen months alone in the Alaskan wild. Sam Keith authored the book based on Dick Proenneke’s journals and photographs. Keith is also the author of First Wilderness: My Quest in the Territory of Alaska, another Alaska Northwest Book.

Hoping to learn more about the man and the book, I emailed a set of questions to Brie Anderson, curator of the Richard L Proenneke Museum, and she responded with everything I was hoping for. One Man’s Wilderness has marked me forever.

It’s difficult to imagine the courage needed to winter alone in such a hostile environment, hundreds of miles from anyone else. Did he ever privately express any particular fears? Was the danger part of the attraction for him?

Making the decision to spend the rest of his life at Twin Lakes was not a snap decision. He had prepared his entire life for this. It wasn’t courage, or fear, or being intrigued with danger, it was the next step in his life’s journey. The accumulated life lessons Richard experienced throughout his life prepared him to put himself and his self reliance to the ultimate test with Mother Nature—to know and understand Mother Nature intimately as no other would, what Mother Nature is capable of offering us, and what She can take away in an instant.

Dick was remarkably knowledgeable about plants, animals, weather, and just about all branches of the natural sciences. He just seemed incredibly curious about everything. Where did he acquire all that knowledge?

Growing up in a farming community during the Great Depression gave Richard a solid foundation that would carry him throughout his life. He would continue to expand his love of nature, the animals, understanding how the weather plays into farm life into every situation and experience he encountered. He had a keen sense of observation, and was extremely curious about how things worked in the grand scheme of things.

Dick was also a highly skilled carpenter, judging by his ability to build a beautiful, functional log cabin—including stone fireplace and chimney—using hand tools. And his fix-it skills knew no bounds, from making intricate repairs to his cameras to fashioning a snow shovel out of a fifteen gallon oil drum. What jobs did he have earlier in life that left him so prepared for his Alaskan experience.

Again, it was the solid foundation he lived growing up in a farming community. They were very pragmatic and practical. Back then electricity was rare in the rural areas of Iowa, and nearly everything had to be accomplished by hand. It was a time when families were self-sufficient, and the Proenneke family was self-motivated, self-taught, and expected no hand-outs. Prior to building his cabin, Richard’s first efforts of log building came when he built the Alsworth’s a hen house.

Throughout the book, Dick makes mention of his disdain for the shoddy behavior of the wealthy hunters who would come north to hunt with professional guides. They’d leave piles of trash, and quite often neglect to fully dress out the caribou they killed and instead just saw off antlers for show and tell. Where did he develop his spotless sense of sportsman’s ethics?

He learned as a youth not to waste anything, to use and re-use everything. Nothing was thrown out unless it had finally become useless. Richard quickly realized the animals in his surroundings had it difficult enough trying to survive without having to deal with hunters. In the more than thirty years he spent at Twin Lakes, Alaska, he only shot one ram, the first year for food, and it bothered him immensely because he realized it was far too much meat for one person, and was such a waste.

Over time Richard realized by observing animals that a simple diet of food was plenty. Take no more than you need, use everything you take, it need not be fancy. The hunters had no interest in the animal they hunted, it was just a trophy to them. Richard wanted people to pay attention to nature and to the animals surrounding them. This was Richard’s sanctuary, and these hunters had no respect for his surroundings. Richard was always picking up trash left by hunters and campers. It was an insult to him that people would come into his world and show such disrespect.

He also earned a great deal of satisfaction from a full day’s work, especially one that left him exhausted. Keeping up with cutting and stacking firewood everyday would have been overwhelming to most men, but that was just a trivial chore for Dick. In the preface, we learn that he was bedridden for six months with rheumatic fever during World War II. Was that debilitating experience influential to his life? Was he an athlete in earlier days?

Richard’s work ethic came from his upbringing. Life was very difficult on the farm, but also very rewarding. It also allowed creative thinking and imagination to emerge—from making and flying model airplanes, first powered by rubber bands, then with small gas engines, to rebuilding one after it crashed; helping his older brother build a small wind generator; and rewiring a generator boosting batteries and powering the lights in their house. Richard was not an athlete in the normal way. There were two modes of transportation at Twin Lakes, by canoe, or by hiking. Richard was an insatiable hiker, and even in his seventies would and could out-hike those much younger than he.

There is a very fine line between life and death, and it seemed Richard was right up to that fine line throughout his life. On Richard’s twelfth birthday, his younger brother Paul died at age twenty one, in a motorcycle accident, while Richard only sustained minor cuts and bruises; surviving rheumatic fever while on a lay-over in the Navy, when so many did not; and nearly losing his sight while helping a welding contractor, are a few notable examples. His fortitude and endurance and self-determination to conquer whatever was being thrown at him is a testament to him.

Dick and his bush pilot friend, Babe, had a interesting, complex relationship, though certainly one of friendship and mutual respect. Interestingly, Babe was devoutly religious and vocal about it, while Dick seemed more agnostic in his beliefs. These differences sometimes made for testy conversations. Can you tell us more about their relationship? When and how did Babe die?

I don’t consider Richard an agnostic, he simply had a different way of thinking and believing. While Babe and he would have quite the discussions where religion was concerned, Babe was into the ritual and details and intricacies about his religion; Richard’s viewpoint was much broader, in that he saw the beauty and grandeur of God’s creation all around him, eventually becoming one with nature, transforming himself along the way. His spirituality was deeply intimate, yet so very simple. There was beauty in life all around, and one only had to notice it, appreciate, and respect it. The Alsworth family and Richard were more than just friends, their souls were intertwined with each other. Babe and Mary, their kids and grandkids were Richard’s lifeline and in turn, there was nothing Richard wouldn’t do for the Alsworths. Among the multitude of things Richard did for the family was to build the runway for their planes at Port Alsworth. Babe’s two grandsons, Sig and Leon Alsworth, would spend a couple of weeks at Richard’s cabin in the summer. He thought so much of these two little tykes, that when Richard followed the movements of a Mother Grizzly one year, he named her two cubs after them. Leon is still a park ranger today at Lake Clark NPS. Babe died in 2004 at the age of 94.

Was Dick an avid reader? Can you name some authors and books he loved?

Yes, Richard read a variety of things, his curiosity had no limits. He was also a voracious writer, answering thousands of letters he received over the years. At one time on his bookshelf, Richard had the Merriam-Webster Dictionary; Glacier Pilot; The Quiet Crisis; Field Guide to Rocks and Minerals; a book on the Shikar Hunting Club; Alaska Wilderness: Exploring the Central Brooks Range; Lake Clark-Iliamna, Alaska, 1921: The Travel Diary of Colonel A. J. Mcnab, with related documents by A. J. Mcnab; Arctic Wild; Reverence for Wood; Diary of an Early American Boy; Planet Steward; Journal of Wildlife Sanctuary; Travels in Alaska; Two in the Far North; A Sand County Almanac (Outdoor Essays & Reflections); In Wilderness Is the Preservation of the World; Monarch of Deadman Bay; The Life and Death of a Kodiak Bear; The Red Snow: A Story Of The Alaska Gray Wolf; Bittersweet Country; Outdoor Photography: Specially for Hunters, Fishermen, Naturalists, Wildlife Enthusiasts (Outdoor Life Skill Book); Tanaiana Plantlore; Island Between; Lonely Land.

Was he ever married or in a relationship?

Richard was a confirmed bachelor, liked women, and had many women friends. There were many ladies who had a huge crush on Richard, some even visited him at Twin Lakes. I often hear from ladies who, still to this day, have a crush on him, but have never met him.

Final comments:

Richard left school during his sophomore year and chose instead to further his “education” by working on nearby farms, driving tractors, doing all sorts of mechanical and building repairs, caring for animals and the multitude of daily chores associated with farm life, and learning as much about the workings of machinery and equipment and teaching himself what one must do to maintain a family farm. He seemed to have the ability to fix about anything. Richard and his brothers loved motorcycles, particularly the Harley Davidson, were fascinated by airplanes and aviation.

His restlessness and need to experience life led him to explore what lay beyond the Midwest. At age twenty three, Richard and a friend made a trip west to see the country on their Harley Davidsons. With only $30 in his pocket, along the way, they harvested wheat in Oklahoma, picked apples at Hood River, OR, headed down the Pacific coast, took in the World’s Fair in San Francisco, then on to Los Angeles, CA, and Albuquerque, NM. When they returned to Primrose, IA, Richard had $10 in his pocket.

Richard had visited the Frank Wilkinson ranch in Heppner, OR, and in the spring of 1940 returned to work there, setting up remote camps for herders grazing their sheep and cattle. He worked there until the day after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Richard joined the US Navy on December 8, 1941, became a carpenter’s mate, was sent to Pearl Harbor where he worked for nearly two years. The war ended while he was still recovering from rheumatic fever and received a medical discharge from the Navy in 1945. He returned to the ranch and worked there till 1949. Needing to move on, he ended up in Portland OR, where he signed up for a course for heavy equipment operators.

Late in 1949 Richard made his first trip to Alaska to visit a friend he had met in Oregon, Jack Ferguson. In April 1950, Richard moved to Alaska hoping to start a cattle ranch, but abandoned the idea after consulting with ranchers. He worked at the Kodiak Naval Station, and fished commercially for salmon at Chignik, and worked for the US Fish and Wildlife Service at King Salmon. Richard also worked as a powerhouse operator and mechanic at a satellite tracking station on Kodiak Island. When the Alaska earthquake hit in 1964, Richard was hired by the owner of a thirty-two foot fishing boat to return it to the bay after being blown two miles inland. It took Richard and a friend three days to complete the job.

In 1965, while helping a welder pour a big ladle of molten lead metal, there was a big explosion. The molten metal came out just like snow, hit Richard in the face and into his eyes. It would be several years before he completely healed.

Richard made his first trip to Twin Lakes, AK, in 1962 at the invitation of Spike and Hope Carrithers. He would return again and again because he knew he had found “home,” and in 1967 scouted out where he would build his now famous Twin Lakes Cabin.

In Richard’s Words, “You didn’t have to have a lot of money to enjoy life. There was beauty in life all around you and you only had to notice it and appreciate it.”

Richard spoke of needs, saying: “I get back to what bothers so many folks—they keep expanding their needs until they are too dependent on too many things and too many other people. I wonder how many things in the average American home could be eliminated if the question were asked: must I really have this?”

Also, “Funny thing about comfort—most people don’t work hard enough physically anymore and comfort is not easy to find. It’s surprising how comfortable a hard bunk can be after you’ve come down off a mountain.”

And, that, my friends in a nutshell is Richard Louis Proenneke, a complex man of simplicity and purity. To this day, he continues to inspire generations to do the same.

Please note: The Donnellson Library published A Life In Full Stride – The Journals of Richard L Proenneke 1981 – 1985

Matt Sutherland