Public Libraries Should Adopt Little Free Library Model to Better Serve Community

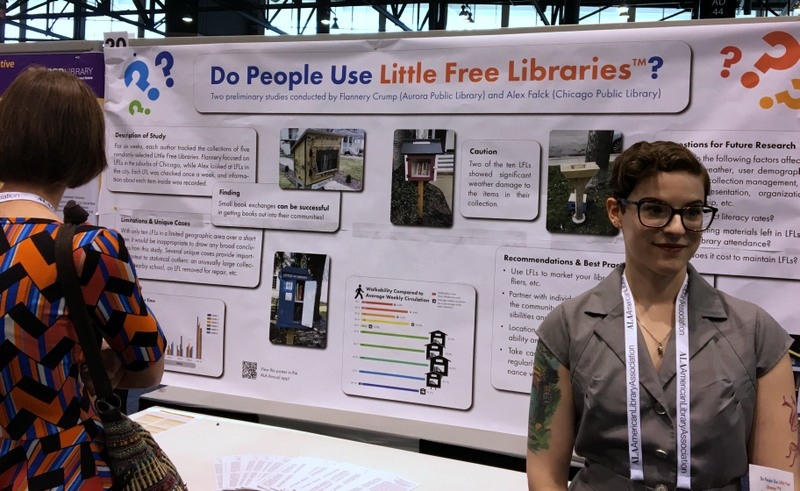

Flannery Crump of Aurora Public Library presents her findings on Little Free Libraries in June at the American Library Assocation's Annual Conference in Chicago.

They’re cute, they’re tiny, they’re full of free books. Little Free Libraries are birdhouse-sized structures that allow locals to take and leave literature at will. No fines, no fees, no cards. Just human kindness and tons of cute. And, of course, there’s the Little Free Library nonprofit, a fourteen-person outfit from the Midwest whose idea has spread around the world. There are now over 50,000 registered Little Free Libraries around the globe, mostly located in the United States.

Normally, the assumption with a Little Free Library is that private citizens will own, curate, maintain, and decorate the structure. This may be the single biggest reason for the Little Free Library’s (let’s just call them LFLs) success. We live in the age of she-sheds, tiny houses, and the ubiquitous mobile phone. LFLs are a bridge in. They gather neighborhoods together like a water cooler. In a culture scripted by the daily march to and from the office, they represent randomness, adventure, an alternative to the bookstore.

Librarians have been aware of (and debating) LFLs for a while. That’s what we do: a new thing comes up and we intellectualize. However, the rest of the reading universe has happily bought into LFLs unreservedly. A dose of each strategy is appropriate. A citizen-fronted LFL movement, while adorable and eminently worthy of Instagram, has some weak points. For example, LFLs tend to appear in wealthy, white, highly educated neighborhoods where people own their own houses and have time to build a teeny cutesy little book repository from a kit that costs a nonzero amount of dollars. There are also the inevitable buzzkills and towering small town drama fests that accompany any nice idea. Critics claim that LFLs are status symbols that do more to announce the liberal crunchiness of an expensive neighborhood than they are revolutionary knowledge drops.

LFLs Evolving Social Legs

However, the idea is also demonstrably good. Police departments and abutters of low-income areas have opted to place LFLs in front of department headquarters and schools either at their own expense or through programs. Maybe it’s not universal altruism, and maybe LFLs appeal most to curators inclined to slacktivism, but they’re clearly evolving social legs on their own. And as we all know, anything that can waver unsteadily to its own feet is ripe material for a librarian to organize, supersize, and distribute with attached cross-promotion and ongoing statistical follow-up. So, of course, that’s exactly what Flannery Crump (Aurora Public Library) and Alex Falck (Chicago Public Library) did. They featured the results of their study on an expansive posterboard at the American Library Association’s 2017 annual conference.

Those results are well worth noting. Crump and Falck found that high-traffic areas were better for LFL circulation than suburbs. Assuming that most bedroom communities house more vehicle commuters than foot traffic, this finding implies that LFLs may have untapped potential in ignored and downtrodden neighborhoods, where people may tend to live in apartments, ride the bus, and walk. “You can put inserts into each item promoting library services and programs,” explains Crump. “There’s also a potential to place [LFLs] in unincorporated areas of town that are not being served by the library already.” And as for safety, Crump continued, “we have not observed any vandalism at any of our locations.” The main problem she ran into was weather, which destroyed an LFL Tardis.

Guidelines already exist for private citizens opting to keep a Little Free Library. It could hardly be easier to personally set out free books if you’ve got the resources, and few rational adults would take issue with the idea of sharing. (Small-town drama royalty notwithstanding.) But public libraries have unique and concrete concerns that LFLs could specifically address.

For one thing, most people without a home address also can’t get a library card. That means that a kid living in the back of his mom’s car can’t borrow a book on computer programming and a migrant farm worker can’t take out an English language resource. Low-income households generally hold fewer books than high-income households by orders of magnitude, and the fact that librarians need to go home at night only contributes to this situation. Libraries being stuck in one big building, the distribution of books to people of limited mobility and time resources is also a major problem. And, not for nothing, but every public library I’ve ever worked in has been plagued by a constant and crippling deluge of book donations.

Why not get those surplus books out of the building and into the homes where they’re needed most? No late fees, no privacy woes. It’s hard to top a public relations campaign like this one, especially if it gets word of free library programs to down and out sections of town. The mere idea that a library cares enough to reach out can be revolutionary for a neglected community. And, at risk of being reductionist, this seems comparatively easy. You can turn it into a program. Forty bucks registers your official LFL—but why even worry about that? Goodness knows there’s no patent on a box full of books.

Greatness Together

And experience bears out the idea that LFLs and publics are destined for greatness together. Crump and Falck represent just two library systems out of many that already incorporate boxes of books stuck on poles all over their communities. Indiananapolis, located in a state where the illiteracy rate is 8 percent, boasts a particularly impressive array of big free libraries, which the public library maintains. Public library-run LFLs are positively rampant in Ohio. Others exist in Arkansas and Florida. There are some on the Appalachian Trail. Really.

Libraries constantly cast for new innovations. 3-D printers, coding classes and coloring clubs have helped to change the image of the entire profession, to our benefit. Enough of us (myself included) cringe when patrons persist in the idea that we’re dead tree repositories made up of particularly avid readers. There is more to a library than the printed word. That said, there are still patrons out there who can’t get a good book. Let’s innovate about that.

Anna Call is a reference librarian at the Nevins Memorial Library in Methuen, Massachusetts. Follow her on Twitter @evil_librarian.

Anna Call