“Queerness exists, even if it’s not verbalized” | Talking allyship in language w/Serkan Görkemli, author of Sweet Tooth & Other Stories

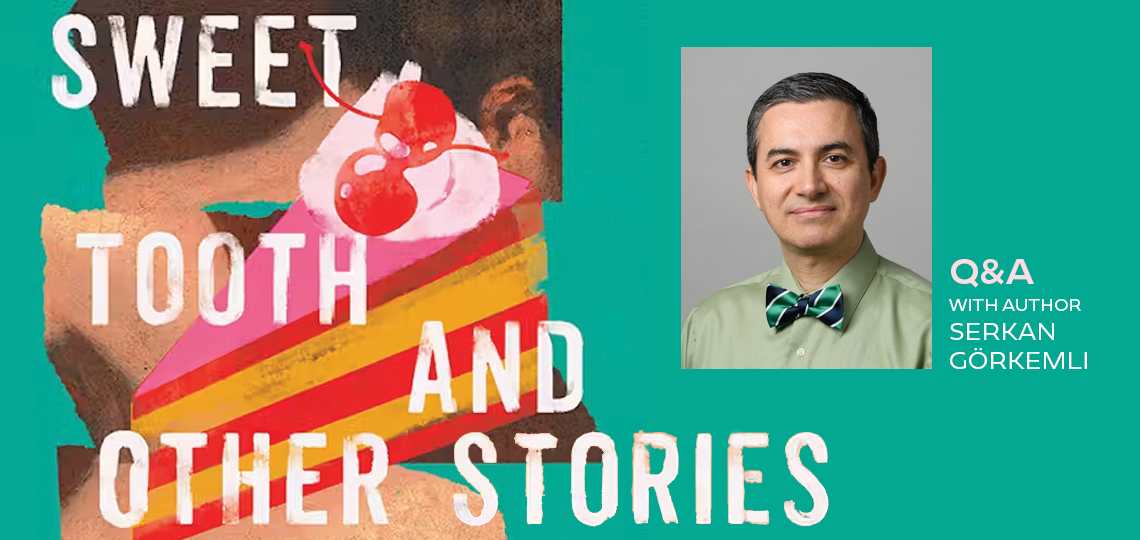

A Conversation with Serkan Görkemli, Author of Sweet Tooth and Other Stories

As a storytelling platform, the short story offers intriguing possibilities for both writers and readers, in a similar way to its nonfiction cousin, the essay. Readers approach both shorter forms with expectations of concision, while writers often charge their fictional stories with essay-like factual detail and knowledge as if they sense their readers want to learn something, in addition to being entertained.

In his spare, though richly descriptive Sweet Tooth and Other Stories, Serkan Görkemli gives readers an intimate portrait of everyday Turkey—social norms, cultural nuances, historical allusions, LGBTQ slang, and more. Raised in Turkey and a former English major at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul, Serkan’s prose finds that sweet spot for readers hankering for short fiction with substance and polish.

Foreword’s Executive Editor Matt Sutherland caught up with Serkan to discuss writing, Serkan’s childhood, queer life in urban Turkey, and what’s next for his talented pen.

In all your stories, you give readers a high level of detail about Turkey, specific villages and neighborhoods of larger cities like Istanbul, as well as the quirks and idiosyncrasies known to the Turkish people, such as the tidbit about a gossipy woman in Big Sister wearing “a string necklace weighed down by small gold Republic coins with the head of the founding father Atatürk on one side and ‘Türkiye Cumhuriyeti 1923’ on the other.” Can you talk about your connection to Turkey and why the country is an important part of your writing?

I was born and raised in Turkey and lived there until I moved to the US for grad school in 1998. I maintain many ties there and visit my family and friends annually, so Turkey will always be a big part of who I am. In terms of my writing, my fiction is often inspired by places I’ve been to or people I’ve met, so Turkey, the crossroads of East and West, where I spent my formative years, occupies an important place in my heart and is a rich source of material and inspiration. While Turkey has provided most of the raw material for my short-story collection, I wouldn’t have been able to conceptualize and write this book, and particularly to write in English, if I hadn’t come to the US. I did start learning English, mostly grammar and vocabulary, in middle school in Turkey, and my partial immersion in the language during literature classes happened as an English major at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul. But my full immersion, not only in language and literature but also in LGBTQ+ culture, happened later, after I arrived in the US, and I needed both to be able to write this book.

For those of us unfamiliar with the Turkish language, will you give us a sense of its character and descriptive qualities? How is it to write in English with Turkish haunting your thoughts?

A few differences between Turkish and English come to mind. The sentence structure is different (subject-object-verb in Turkish versus subject-verb-object in English); there are a lot of suffixes that are added to the end of words to convey tense, pronoun, possessive, etc.; and the third-person pronoun is gender-neutral, like the more recent singular usage of “they” in English—but of course, the Turkish mind is binary gender-colonized, too, so if a speaker cannot figure out a third person’s gender from the context, they’ll ask if the person being discussed is a man or a woman.

In terms of my writing in English, I’m more preoccupied by how to best convey the flavor of Turkish in English than by its sentence structure and grammar. I used to translate from Turkish to English in the early stages of learning English; I do less of that now, but of course, I think about Turkish more when I’m writing in English about Turkey, when my Turkish characters are supposed to be speaking Turkish. I make sure to avoid typical English expressions and regionalisms where possible, and to include Turkish words and interpret idioms to gently remind my English-speaking readers that most of the dialogue they’re reading is between Turkish speakers. So, I’m negotiating two languages and how much I can get away with in terms of including Turkish words or sayings without confusing or taking my reader out of the flow of the story.

Recently, I read from my book at the Center for Fiction in Brooklyn during its “All Pride, No Prejudice!” event, a Pride Month literary LGBTQ+ celebration, and a reader who bought my book asked me to sign it in two languages for his friends, a gay couple where one was Turkish and the other was not, so I had to take a moment to reboot my brain to think about what I’d write in Turkish versus English! That was funny.

Finally, in terms of the descriptive qualities of Turkish, the word hüzün, which can be translated as a combination of nostalgia and melancholy, has been used to describe Turkish literary prose. Regarding whether my writing has hüzün, I’ll let the readers be the final judge of that, but my stories do often take a “what could’ve been” approach to relationships as my characters navigate the loss of family and friends when they come out as LGBTQ+ and search for acceptance elsewhere.

Turkey is also a predominantly Muslim, hyper-masculine country which forces it LGBTQ population into a precarious existence—a fact that isn’t well understood or appreciated by readers in more progressive countries. Please talk about your interest in writing about these men and women.

I write about them because I’m one of them, and yes, the orthodox, anti-LGBTQ+ interpretations of Islam and heterosexual masculine norms are roadblocks to queer liberation in Turkey as I show in my stories. But these roadblocks haven’t always been there. There’s a homosocial aspect to the historically gender-separated Muslim culture; it’s acceptable (and indeed, expected) for women and men to spend a lot of time with people of their own sex. But with heterosexual marriage as the expected destination, homosexuality has become the red line, so to speak, that one is forbidden to cross, yet it happens. In addition, Turkey has a long secular tradition, and there’re different branches and interpretations of Islam, which can create space for LGBTQ+ folks.

I was brought up in a Sunni household, where I was taught that it was not okay to be LGBTQ+ according to Islam. But I also learned that faith was personal, so I now identify as being spiritual rather than religious, and I believe that “gay” is what I’ve been meant to be all along, and that as long as I do good in this world, I’m okay. It’s like what the father says about his gay son’s drag queen boyfriend in the closing story Ingenue: “Allah must’ve created him that way.” That line is based on a news article a Turkish friend once told me about, where a father in Anatolia expressed that sentiment. There are indeed Turkish parents who can adjust their thinking to embrace their LGBTQ+ children and contribute to the movement toward rights, despite what the society at large currently thinks.

In Webbed, we follow Hasan down a hospital corridor on his way to an operation to have the webbing between his ring and middle fingers removed so that, his parents say, he can wear a wedding ring when the time comes. Occasionally, Hasan thinks back on childhood memories which suggest conventional marriage may not be in his future: his eyes stinging in darkened smoke shops with his father and cardplaying friends where he “endured probing questions about school and girls;” a dreaded first haircut to look more like the boy his dad wants him to be; rolling on a rug naked as a five year old with another boy his age. This story sets up the rest of the collection. What was it like to tie these nine stories together?

Webbed is the opening story because it’s chronologically the first, and thematically, it encapsulates what’s really at stake for my characters. Initially, I wrote each story as a stand-alone piece because I was trying to publish in creative writing magazines to build and demonstrate interest in my work. When it was time to shape the stories into a book and to pitch it to agents and presses, I decided to closely interlink the stories, with four main repeating characters. This meant rewriting certain parts and expanding on others to create causality across stories, as well as character growth. These major revisions enabled me to enhance plot points and thematic connections between the stories and to add further emotional depth to my characters as they progressed from early to later years of their lives across the book. All this assumes that readers will read the book in a linear fashion, which may not be the case.

A writer friend recently told me that he read my book backwards and found the thread in images rather than characters, so images are connectors, too, and what they say is true: let your book out into the world and watch what happens!

In Big Sister, a wispy, redheaded young woman named Nazlı Abla is followed from afar by thirteen-year-old schoolboy Gökhan. When one of his grandmother’s friends caustically refers to her as an ablacı, he is confused. Later he remembers his father referring to male celebrities who wear dresses and makeup as nonoş and starts to put two and two together. “That is when it struck me that ablacı might be an insult the older generations used for women who weren’t womanly somehow.” And he notes other words—sevici, lezbiyen, sapιk, top, ibne—which get bandied about in conversations above his head. Finally, at the end of the story, Gökhan thinks to himself after a short, unnerving, but encouraging conversation with Nazlı Abla, “if a word is repeated often enough, it loses its meaning for a moment.” It’s a fantastic story, written with humor and lightness, made all the more memorable by Gökhan’s understanding that Nazlı Abla is somehow a kindred spirit. How did this story come together? The scenes with Gökhan eavesdropping on his grandmother and her gossipy friends are delightful.

Nazlι’s refusal to get married sets in motion the events of the story. Mainstream Turkish culture is very marriage and reproduction-oriented (no same-sex marriages or unions are recognized). When I was growing up, there were perhaps one or two unmarried adults in my entire neighborhood. Women I grew up around would talk about them and sometimes even pity them for somehow failing to get to the culturally expected destination of being wedded and having children. As I first drafted this story and replayed my childhood, I thought about what it meant if one chose not to get married despite tremendous social pressure and judgment. I also knew that not being married in Turkey was a way of possibly being queer without claiming a public LGBTQ+ identity, like having space without verbalizing it.

My next thought was what if one of the few unmarried individuals I knew back home were queer? What would that mean in terms of their life prospects and for the queer youth around them, who’d overhear people gossip about them? So, that was the premise of that story—how queerness exists, even if it’s not verbalized. Or, if it’s spoken of, how it gets demonized, and how it could affect the young woman and the schoolboy in the story who search for affirmative language while facing down incredible odds in embracing their identity. Navigating that process happens in language, and it’s in language that their unexpected allyship emerges as the story unfolds.

By the way, I first drafted Big Sister back in the fall of 2016, when marriage as an institution was certainly in my mind; New York, where I live, legalized same-sex marriage in 2011, I married my long-time same-sex partner in 2014, and the SCOTUS extended this right to all states in 2015. As I wrote the rest of my book, I thought about same-sex marriage and read its queer critiques on the grounds of assimilation and homonormativity, so I returned to the topic in the story Runway later in my book.

As mentioned above, you sprinkle in the Turkish LGBTQ vernacular throughout the stories, slang Turkish words that phonetically seem to mimic the English version. From a language standpoint, how has American English influenced Turkey and, especially, its LGBTQ population and gay rights movement? And more generally, how is Turkey’s LGBTQ+ community handling these years of repressive government?

Same-sex contact and practices have always existed in Turkey; they may not have been public, but there’s language that evidences those practices and practitioners, and my characters use those words in my stories. That outdated language, however, is mostly negative and refers to acts, rather than identities, so the translation, transliteration, and loaning of English words for LGBTQ+ identities, such as eşcinsellik for homosexuality, gey and lezbiyen, and trans, into Turkish has helped fill the gap for words for identification with non-normative genders and sexualities and have therefore been mostly empowering.

Such language change is not unusual; as a descendant of the imperial Ottoman language, Turkish already has thousands of words from other languages, including Arabic, English, French, Persian, and Urdu. The dialogue in my story Runway even includes a subcultural raunchy patois called “lubunca,” a combination of Romani and Turkish originally used among the working-class, urban queer populations, that more recently has been partially adopted as an insider language among urban mainstream LGBTQ+ Turks.

As for movements, Turkey has a robust history of LGBTQ+ activism that has yielded advocacy organizations and student clubs on college campuses across the country, which I wrote about in my first book, Grassroots Literacies: Lesbian and Gay Activism and the Internet in Turkey. The arrival of LGBTQ+ representations through global media and the adoption of those identities by individuals and groups of people inevitably led to demands for recognition in the form of non-discrimination protections and hate-crimes laws, similar to what happened in the US. The governmental response has thus far ranged from the flat denial of queer people’s existence to a sort of grudging admission in the form of denunciation and local bans, including the banning of the annual Pride March in Istanbul as mentioned in my story Pride.

The flip side is that LGBT identities have never technically been outlawed. There are now a few elected LGBT-identified or -friendly politicians, and there is direct or indirect support for LGBT rights among a few opposition parties. There is ongoing activism to change people’s minds and elect more sympathetic politicians, in order to provide much-needed services and advocacy locally and transform politics nationally. This community organizing / coalition building is happening despite the increasing anti-LGBTQ+ political rhetoric.

There’s a chronology to the stories, as the characters—Gökhan, Hasan, Nazlı Abla, and others—grow older, but this line from Gökhan in Sweet Tooth hangs especially heavy: “How easy and difficult it is to be one thing on the inside and another on the outside, he thought.” Which, of course, is a fairly universal sentiment but perhaps more acute in Muslim countries. In your mind, is this the case?

I feel I need a couple of qualifiers to answer this question. I’ll first start by saying that my character’s sentiment applies to being an LGBTQ+ individual in an orthodoxly Abrahamic religious community anywhere in the world. And yes, there may be some cultural similarities among Muslim countries that underlie negative attitudes toward LGBTQ+ individuals, hence the possible applicability of my character’s sentiments across the board. Having said that, I’ll focus the rest of my answer on Turkey because I know its history and internal dynamics.

Euro-American LGBTQ+ identities are relatively new to Turkey, so part of the reason an average Turk has reservations about them is because they simply don’t know (or, much more likely, don’t think that they know) an LGBTQ+ person in their everyday lives. Islam, like its Abrahamic siblings, is often interpreted as being anti-LGBTQ+, so that has a negative effect on all Turks whether they identify as religious or not (or even as Muslim or not). But there are other important reasons for anti-LGBTQ+ attitudes, including Turkey’s collectivist patriarchal culture, the entrenched heterosexual and binary gender norms that emphasize marriage and reproduction, and the concepts of honor and shame that are not sex- and sexuality-positive regardless of sexual orientation and gender identity. In my book, I’ve tried to represent as many of these factors as possible, to show how they challenge my characters and what they can do to begin to overcome them (for example, migrate and/or build alliances), but as long as the sum total of these factors, of which anti-LGBTQ+ interpretations of Abrahamic religions is but one, continues building walls around queer people, that vexing duality of private versus public identities will persist.

Your knowledge of ancient Greek and Roman art and history in Turkey informs nearly all the stories and, as a classical history buff, it added a great deal to my reading experience. What gives? Do you have a history background?

I’m pleased to hear that those details enhanced your reading experience! Being from Turkey and having taken courses on history and art throughout my education, including a course on Western civilizations as an English major at Boğaziçi University in Istanbul three decades ago, I gained a fair amount of knowledge about ancient art and history in Turkey, plus I visited numerous museums and famous sites, such as Ephesus and Troy. But of course, writing about a place—a country, a city, a neighborhood, a more specific location, such as a monument or a building with a specific piece of art like in my story Vulcan—involves revisiting what you know about it and then realizing through research just how much you don’t know—there’s a world of information out there! We’re talking about fiction here though, so all contextual knowledge, about art and history in this case, must be subsumed to storytelling and what you’re trying to achieve in dramatizing the trials and tribulations of your characters. So, research is not only unearthing information but also being selective regarding what’s relevant to the story and the characters. Again, thank you for telling me about your positive reading experience, which is very rewarding for a writer to hear.

Please tell us about your life currently? Are you working on another writing project? Teaching?

Sweet Tooth and Other Stories came out in mid-May, so I’ve been busy launching it, which is the more social, public phase of the writing lifecycle. I’ve enjoyed connecting with readers and fellow writers, particularly in NYC, where I live.

I’m also working on my next book of fiction, set in NYC from summer 2017 through summer 2020. In its current iteration, it’s a collection of fifteen interlinked short stories, including experimental flash fiction and traditional, character-driven pieces, about queer Turkish immigrants and their allies navigating the pandemic and the interesting political environment at the time.

Finally, I’ll be teaching four courses at the University of Connecticut in Stamford in the upcoming academic year: Introduction to Writing Studies and LGBTQ+ Literature in the fall, and the Short Story and Creative Writing II in the spring. It’s a pleasure to help students grow as writers and tell the stories that are personally important for them. Discussing writing and literature with them also fuels my own writing, so I’m looking forward to that productive overlap.

Thank you so much for reading my book and for this interview that allowed me to reflect on my influences and inspirations and my process of writing it.

Matt Sutherland